At Roxbury Film Festival, a difficult question: Can white filmmakers make black films?

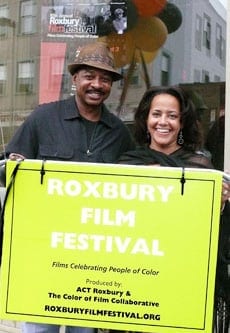

Author: Roxbury Film FestivalActor and producer Robert Townsend (left) joins Lisa Simmons, founder and director of the Color of Film Collaborative, at the opening of the 10th Annual Roxbury Film Festival last week. Townsend’s latest film, “Of Boys and Men,” opened the festival.

White people dealing with race and privilege is also at the forefront of “Traces of the Trade: A Story from the Deep North.”

The documentary follows Katrina Browne after she discovers that her ancestors, the DeWolfs, were the largest slave-trading family in American history.

Browne unites other DeWolf descendants from across the country, and together they visit Bristol, R.I., their ancestral hometown — founded largely on profits from the slave trade. From there, the group travels to former slave plantations in Cuba, where slaves made rum, to Ghana, where the African slaves were shipped off. Gradually, they begin to realize that their own privilege is connected to the historic legacy of slavery.

One of the documentary’s most poignant scenes features a black project co-producer, Juanita Brown, who is coerced into talking to the family.

“If you grew up where I grew up, you’d be pissed off, you know?” Brown says. “Anybody who’s alive or paying attention should be pissed off, and the fact that white people are not pissed off means that they are not paying attention.”

The history of slavery and its long-term effects are addressed in “Black Ice,” which received this year’s Best Documentary Short award. Recovering the nearly lost story of black involvement in the sport of hockey in the late 19th and early 20th century, the movie was directed and produced by white Canadian historians and brothers George Fosty and Darril Fosty.

George Fosty led a brief but animated QandA session after the documentary’s screening. He was joined by Drakeford Levi, who serves on the executive board of the Black Ice Project, which seeks to increase involvement of people of color in ice hockey.

As Levi explained, George Fosty’s race has assisted with the Black Ice Project’s struggle to be taken seriously in the eyes of the hockey establishment, including the National Hockey League.

“It really helps that George is white,” Levi said. “Whenever we talk to [potential financiers], they always suspect that we have some sort of agenda. But what can they say about George, with his intense passion? What agenda could he have except for a commitment to the truth?”

Levi was not the only person at the festival to report encountering racism in the film industry.

Thinking back to meetings with Hollywood studio executives about “Steam,” Schickner recalled being asked to “cut out Ruby Dee’s character.” Nobody wants to see a movie about old women, Schickner said he was told, “especially African American, that was the subtext.”

Schickner also spoke about the privilege accorded to white filmmakers in the studio system.

“I would have friends — much more talented females and much more talented people of color and really much more talented women of color — that were writers, and I would get meetings easier,” he said.

While socially conscious filmmakers like Schickner, Piotrowicz and the Fosty brothers represent only a fraction of white writers and directors working in the film industry, their efforts are nonetheless encouraging.

“My feeling is we have enough films that star straight white men in the world,” said Schickner. “There are other stories to tell.”

Dee later added that while such films can be “true and noble,” they only make up “part of the story,” insisting that it’s up to the independent filmmakers like those at the Roxbury Film Festival to “make films that are not the norm about Africans.”