A reform in disarray

|

|

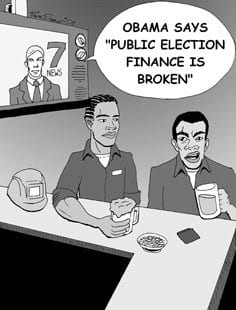

“Well, if it’s broken, then you don’t depend on it.” |

Political operatives understand the axiom, “Money is the mother’s milk of politics.” Politicians who successfully raise the most money enjoy a great advantage over their opponents. Supporters who contribute substantial sums to political campaigns are rewarded for their generosity with extraordinary access to the halls of power.

The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, co-sponsored by Sens. John McCain, R-Ariz., and Russell Feingold, D-Wis., aimed to curb the impact of wealthy donors. It limited the amount anyone can contribute to a candidate in a federal election to $2,300. However, this restriction did not completely level the playing field: There was no limitation on how much a wealthy candidate could spend on his or her own campaign.

The bill did provide some relief to the impecunious candidate. If a wealthy candidate spent more than $350,000 of personal funds on the campaign, then contributors to his opponent could donate up to $6,900, three times the previous limit, until the amount of contributions were equalized.

Jack Davis, a wealthy candidate for Congress who had been unable to overpower previous opponents with his wealth, challenged the so-called “millionaire’s amendment” and won. The U.S. Supreme Court recently ruled in Davis’ favor, in essence deciding that it was constitutionally impermissible to deny the wealthy their electoral advantage.

Presidential candidates also have the benefit in the primary of the Matching Payment Act. Under that statute, anyone who receives at least $5,000 in donations from a minimum of 20 states can receive matching funds from the Federal Election Commission (FEC) for up to $250 from each donor. The candidate must agree to limit campaign expenditures to an amount called the “national spending limit” (about $54 million for 2008), among other regulations.

McCain applied for matching funds and was certified last December. On Feb. 6, however — after his chances of taking the Republican nomination began to look more promising, he wrote a letter to the FEC announcing his withdrawal from the plan. Under the rules, the FEC’s six commissioners must rule on such a request, but they have not been able to do so. The terms of four commissioners expired in January, leaving only two remaining in office. President Bush has not filled those posts, and it takes the vote of at least four commissioners to resolve any issue. The Democratic National Committee has filed suit seeking judicial intervention.

When Sen. Barack Obama announced that he would not be seeking public financing for his election campaign, he was certainly justified in asserting, “The public financing of presidential elections, as it exists today, is broken — and the Republican Party apparatus has mastered the art of gaming the system.”

Wealthy donors can still avoid the restrictions of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act by forming so-called “527 groups,” named after a section of U.S. tax code that covers political organizations. In the 2004 election, as few as 25 individuals contributed $146 million to 527s. The attack on Sen. John Kerry during the 2004 race by the 527 group Swift Boat Veterans for Truth was extremely effective. As long as 527 groups do not collaborate with the campaign of any candidate, they are legal.

The race issue alone provides substantial fodder for 527 groups. The $84 million offered by public financing will not be enough for Obama to fund a positive campaign and finance an effective rebuttal to the expected 527 defamations. Obama’s decision to rely on private financing was a strategically sound decision, essential for victory in November.