King’s legacy has evolved in 50 years following his death

More radical ideas ignored as efforts to memorialize King went mainstream

When Martin Luther King, Jr. was felled by an assassin’s bullet 50 years ago, the news of his death shook the nation.

In the immediate aftermath of the April 4, 1968 murder, violence broke out in 125 American cities, leading to 48 deaths, more than 1,600 injuries, extensive property damage and more than 10,000 arrests. The federal government deployed 57,000 soldiers and National Guardsmen to quell the unrest, the largest force ever deployed for a civil emergency in U.S. history.

While the initial reactions were violent, King’s death left a legacy of positive change in the United States that, while falling short of his lofty aims to build a more just and equitable society, nevertheless had profound impacts on the lives of people of color. As the gains of the civil rights movement in housing, employment and public accommodation solidified in the 1970s, King’s ideas and calls for a nation free of prejudice became more widely accepted.

But not all his ideas. Some aspects of King’s legacy remained controversial in American politics — in particular, his anti-war stance and his calls for trans-racial anti-poverty and labor movements.

King with President Lyndon Johnson as he signs civil rights legislation into law.

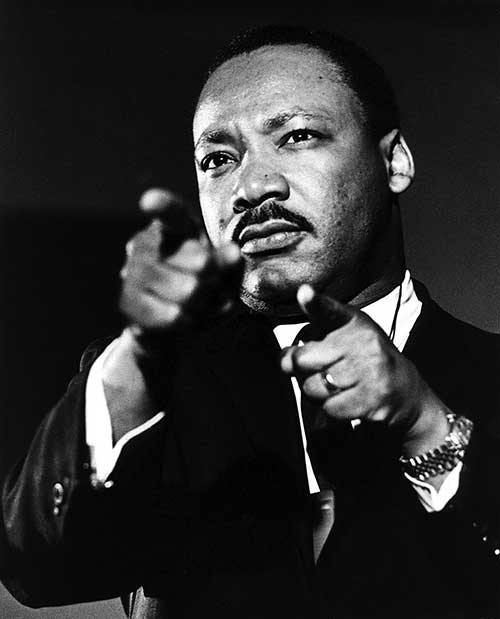

Martin Luther King during the historic March on Washington.

King, the radical

In the months leading up to his death King was outspoken in his opposition to the war in Vietnam and drew fire from critics with his calls for demonstrations against poverty in the nation’s capital. As part of his Poor People’s Campaign, King had planned to create a poor people’s encampment later in April on the 15-block Washington Mall to demand that Congress act to take action on anti-poverty and civil rights initiatives.

King told reporters he was willing to risk being arrested to lead the demonstrations, which had the endorsement of the American Federation of Teachers, the AFL-CIO major civil rights groups and organizations representing Puerto Ricans, Mexicans and Appalachian whites. The planned demonstrations underscored growing dissatisfaction with the Johnson administration’s War on Poverty and pressed for race-neutral policies, including King’s call for a national basic income.

King’s assassination quickly derailed the Poor People’s Campaign, taking with it the activists’ best chance at a broad-based, multi-racial movement. But in the months and years that followed, there were increased responses to the conditions in which blacks lived — the issues that had provided the impetus of the Civil Rights Movement.

Initial response

In the immediate aftermath of his assassination, King’s image in the popular consciousness began to change. His legacy became less about the the Poor People’s Campaign and the controversial anti-war stance that, more than anything else, put him in the crosshairs of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, and more about the heart of the civil rights movement — its call for black equality.

Georgetown University Sociology professor and author Michael Eric Dyson argues that at the time of King’s death, many whites celebrated his passing. King’s image, Dyson argues, has been sanitized with time.

“His danger has been sweetened,” Dyson told National Public Radio in a 2008 interview. “His threat has been removed. There are only smiles and whispers and applause now without the kind of threat that he represented.”

Thus, King’s “I have a dream” speech — which he delivered at the 1963 March on Washington — came to symbolize King in America’s popular consciousness. His anti-war, pro-labor stands from the latter half of the decades, while not erased from history, receded to the background.

Yet even with the sanitized version of King that emerged in the years after his death, the near-universal acceptance of King and his civil rights legacy seen in the United States today took more than three decades to cement.

The King holiday

Boston was an early adopter of an annual holiday honoring King. In 1970, the then all-white City Council voted in favor of the official holiday, with South Boston Councilor Louise Day Hicks casting the sole dissenting vote. While city and state workers did not have a day off, Boston Public School students did, and 34 Boston businesses, agencies and community schools agreed to close on Jan. 15 as well.

King’s birthday did not become a national holiday until 1983 — after nearly 15 years of advocacy by civil rights activists. Much of the initial resistance to the King holiday centered on his ties to communists and his opposition to the Vietnam war.

Massachusetts Sen. Edward Brooke and Michigan Rep. John Conyers first introduced the bill authorizing the holiday in 1979, but it fell five votes short with congressional representatives arguing that U.S. holidays should not be designated for private citizens who never held elective office.

Supporters collected 6 million signatures in support of the holiday in 1980 — the largest petition drive in U.S. history. U.S. Sen. Jesse Helms of North Carolina led opposition, submitting a 300-page document detailing what he said was evidence of King’s ties to communists. U.S. Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York threw Helms’ papers on the floor of the Senate, stomped on it and called it a “packet of filth.”

The bill passed the U.S. House of Representatives 338 to 90 later that year and Ronald Reagan signed it into law. Although the day became a federal holiday, several U.S. states declined to observe the day. In 1990, the National Football League moved Super Bowl XXVII from Arizona to California to protest the state’s refusal to adopt the holiday. Two years later, voters in Arizona passed a statewide referendum to observe the day. In 1991, New Hampshire created a “Civil Rights Day” holiday to mark King’s birthday. South Carolina, the last holdout, marked King’s birthday in 2000, a few months after Utah had moved to do so.

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Cagen-Luse_Men-at-store-e1713991226112-150x150.jpg)