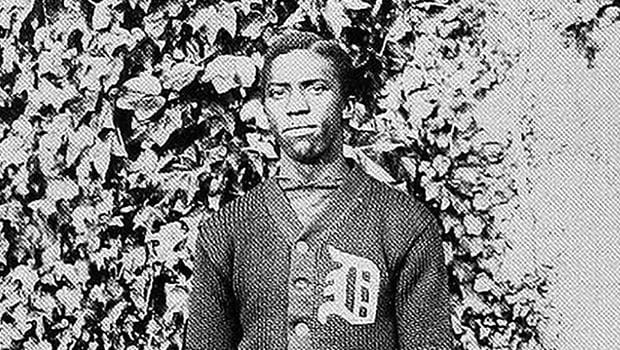

The multitalented Matthew Washington Bullock

Athlete, attorney, coach and teacher first black chairman of Massachusetts Board of Pardons

A star athlete in both high school and college, Harvard-trained attorney Matthew Washington Bullock coached high school and college football, taught at Morehouse College, served as special assistant attorney general for Massachusetts, and became the first black chairman of the Massachusetts Board of Parole and Advisory Board of Pardons.

He was born Sept. 11, 1881, in Dabney, North Carolina. His parents, Amanda and Jesse Bullock, formerly enslaved, poor and illiterate, brought him and his siblings to Boston when he was 8 years old. He recalled, “I entered the first grade of an elementary school on Phillips Street in the spring of 1890.” His family found a home in the West End, first at 14 Gilson Court, then at 29 Anderson Street. There his father earned a living peddling coal and wood.

By 1895, the Bullock family had moved to 14 Winter Street in Everett, where young Matthew attended the Center Grammar School. He went on to attend Everett High School, where he was elected captain of the varsity football and varsity baseball teams in his senior year.

After graduating from Everett High in 1900, Bullock spent the summer employed at the Oxford, a hotel in Fryeburg, Maine. Then, with just a suitcase and $50, he enrolled at Dartmouth College in the fall. Not only was he an exemplary student, but he excelled in sports, playing the right end position on the varsity football team and competing in the high jump and the long jump as a track team member.

Being the only black player on Dartmouth’s varsity football team in 1903 was at times humiliating. When he traveled to New Jersey to play the Princeton Tigers on Oct. 24, 1903, the Princeton Inn, where his team stayed, refused him accommodations because of his color. On top of that, a Princeton player, who was quoted as saying, “We’ll teach you not to bring niggers down to play against us,” intentionally dislocated Bullock’s shoulder in the game. But he persevered.

Well-rounded

In addition to his athletic prowess, Bullock had a love for music. While at Dartmouth, he sang bass in the college glee club and baritone in the chapel choir, and he served on the music committee of the YMCA, headquartered at Bartlett Hall. He was an associate editor of The Aegis, the yearly publication of Dartmouth’s junior class, and a member of Palaeopitus — a senior society whose members were selected on the basis of their demonstrated dedication to the college.

Bullock acquired a bachelor’s degree from Dartmouth in 1904 and attended Harvard Law School, graduating with a bachelor of laws degree in 1907. He worked his way through law school by coaching football at Massachusetts Agricultural College (MAC) and Malden High School. Near the end of the 1904 season, William Anson Munson, captain of MAC’s all-white varsity football team, lauded him, noting, “Mr. Matthew Bullock . . . took charge of the team, and with the hardest schedule which we have ever played has developed one of the best teams the college has ever put on the gridiron.” Munson concluded, “Too much praise cannot be given to Coach Bullock for the work he has done this season. To his conscientious labors and knowledge of the game much of our success is due.”

In 1910, Bullock married 25-year-old Katherine H. Wright, a dressmaker from Middlesboro, Kentucky. They had two children: Matthew Jr., born in1920, and Julia Amanda, born in 1921. Matthew Jr. graduated summa cum laude from Bowdoin College and, like his father, attended Harvard Law School. He eventually became a judge of the Court of Common Pleas in Philadelphia. Julia graduated cum laude from Fisk University.

From 1908 to 1911, Bullock taught economics, history, government and Latin at Atlanta Baptist (now Morehouse) College under the strong leadership of John Hope, its first African American president. While there, he also coached the football team to a record of thirteen wins and three losses. He practiced law in Atlanta from 1912 to 1915 and, thereafter, accepted a two-year appointment as dean of the State Agricultural and Mechanical College for Negroes (now Alabama A & M University) in Normal, Alabama.

Bullock gained admittance to the Massachusetts Bar on Sept. 11, 1917. That year, he tried to enlist in the U.S. Army to fight in World War I, but was rejected for service because he had a slight heart murmur. Not one to give up easily, he became educational secretary for the YMCA at Camp Meade in Maryland, serving from November 1917 to January 1918. And on Feb. 20, 1918, he boarded the ship Rochambeau for France as a special representative of the National War Work Council of the YMCA, and assisted in its war effort overseas as an athletic director, choir leader and French language instructor. He completed duty in May 1919.

Politics

A prominent leader among black folk of Boston’s South End and Roxbury, Bullock had political aspirations. Seeking to represent the 13th Suffolk District, he and African American physician Andrew B. Lattimore ran for state representative as Republicans in 1920; however, Democrats Frank J. Burke and Timothy J. Driscoll defeated them in an election tainted by voter intimidation and explicit racial appeals. Blacks charged that on the day before the election they received circulars headed, “Massachusetts Election Commission, State House, Boston, Mass.,” charging that they had illegally registered to vote and warning them against voting in the election. Additionally, Bullock and Lattimore asserted that, though they conducted a clean campaign, their white opponents, having been “soundly beaten on the real issues,” distributed cards exhorting the voters of Ward 13 to “re-elect two white representatives, Burke and Driscoll.”

After that unsuccessful bid, Bullock ran for the seat again on Nov. 7, 1922. In that campaign, he and Jessie F. Emery secured the Republican Party nomination but lost the election to Democrats Richard Daniel Gleason and Edward F. Wallace.

Bullock, whose grandfather was killed by the Ku Klux Klan in the South, wanted to ban groups that promoted racial hatred. On Oct. 23, 1922, when he was a candidate for state representative, he filed with the clerk of the House a bill to prohibit the organization of the Klan in Massachusetts, declaring it “a menace to the public peace.” Under the proposed measure, any person who joined a society or order of the Klan within the state would have been subject to a fine of $500, two years imprisonment or both.

State appointment

In 1924, Attorney General Jay R. Benton tapped Bullock for the post of special assistant attorney general for Massachusetts. In that position, he was responsible for assisting the Metropolitan District Commission in performing any legal work that arose out of the construction of the Northern Artery — a highway running from Boston to Somerville’s Wellington Bridge.

In 1927, Gov. Alvan T. Fuller appointed Bullock to the Massachusetts Board of Parole and Advisory Board of Pardons, where his chief concern in considering prisoners for parole was the safety and welfare of the public.

As a state parole board member, Bullock attended the National Crime Conference in Washington, D.C. in December, 1934. On his first day there, he suffered the indignity of being treated as a second-class citizen. Invited to call at the suite of his colleague, parole board member P. Emmet Gavin, when he entered the hotel where Gavin was staying, an employee directed him to use the freight elevator. Bullock indignantly replied, “Why, I don’t intend to use the freight elevator.” He called Gavin, informing him that he had been denied use of the regular hotel elevator. Incensed, Gavin advised him to wait outside and, with other members of the Massachusetts delegation, confronted the hotel manager and threatened to leave immediately unless Bullock was promptly admitted and treated courteously. The hotel yielded to Gavin’s demand and there was no further trouble, as Bullock found its staff both courteous and apologetic.

At that conference, Bullock presented a resolution recommending the adoption of the Costigan-Wagner Anti-lynching Bill, which would have made it a crime for any law enforcement officer to refuse to protect a person in his charge from a lynch mob. He argued that drastic legislation was needed because lynchings were “undermining the social fabric of the nation,” and the states in which the crime had been committed had “constantly failed or refused to give protection.”

Succeeding governors reappointed Bullock to the Parole Board, on which he served until 1936, when he was named division director of the Department of Correction. During his six-year appointment, Bullock and his family moved from 56 Windsor Street to 101 Munroe Street in Roxbury. He returned to the parole board in 1943. The following year, Governor Leverett Saltonstall appointed him to parole board chairman at an annual salary of $9,000, making him the first African American to serve as chairman and, likely, the highest paid one in public service in Massachusetts at that time.

Bullock left for the South Pacific on Sept. 23, 1945. Navy Secretary James V. Forrestal had appointed him to a commission of six men to study racial conditions among enlisted men stationed there during World War II. The findings of the commission were relied upon to begin the process of racially integrating the U.S. Navy.

Reformer

As parole board chairman, Bullock promoted reasonable prison reform. He advocated a policy of separating adult convicts from juveniles, saying, “We need a system where prisoners can be properly classified and housed. Hardened prisoners don’t belong with youngsters.” On Aug. 30, 1948, at the annual Congress of Correction in Boston, Bullock remarked that “imprisonment as merely a punitive measure” had “not served to reduce crime.” He said that since 95 percent of U.S. prisoners were at some point paroled, prisons needed to do more than simply punish criminals, and he urged a policy of preparing them for their release as the major objective of all correctional institutions.

On occasion, Bullock gave lectures. At the twenty-third annual convention of the Northeastern Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs at the Olney Street Baptist Church in Providence in 1919, he spoke on the work of African American troops in France. In 1921, he delivered a lecture before the Everett Board of Trade entitled, “The Negro: A Great Asset.” And on Christmas Eve, 1933, he took as the topic of his address “Can Races, Creeds and Classes Live Together in Peace?” He said, “I say there can be no peace as long as this country gives itself to segregation, as long as the black man does not have the freedom of the court, as long as the colored people of the South are prohibited the right to vote and have their vote counted, and as long as social customs of the country draw a line of demarcation.” He added, “The black man has the right to demand the ordinary rights and privileges of American citizenship, and when that day comes then we can meet on Christmas and really say, ‘Peace on earth.’”

In March 1963, Bullock took issue with Boston Police Commissioner Edmund L. McNamara’s claim before the Boston City Council that police officers in patrol cars were more effective at deterring crime than those who walked the beat. Bullock informed the council, “We don’t need men in cars. We need the man on the beat who knows every family.”

Honors

Bullock served as executive secretary of the Boston Urban League, and he was a member of the board of directors of the Boston Center for Adult Education and the executive board of the Law Society of Massachusetts. He served on the Boston Zoning Commission as well, having been appointed by Mayor John F. Collins in June 1965.

Dartmouth College awarded Bullock an honorary degree at its 201st commencement on June 13, 1971. At the age of eighty-nine, he was a recognized leader of the Baha’i faith and had traveled all over the world in the interest of the religion. He died in Detroit on Dec. 17, 1972, leaving behind his daughter, Julia A. Gaddy of Detroit, and his son, Matthew W. Bullock Jr. of Philadelphia.