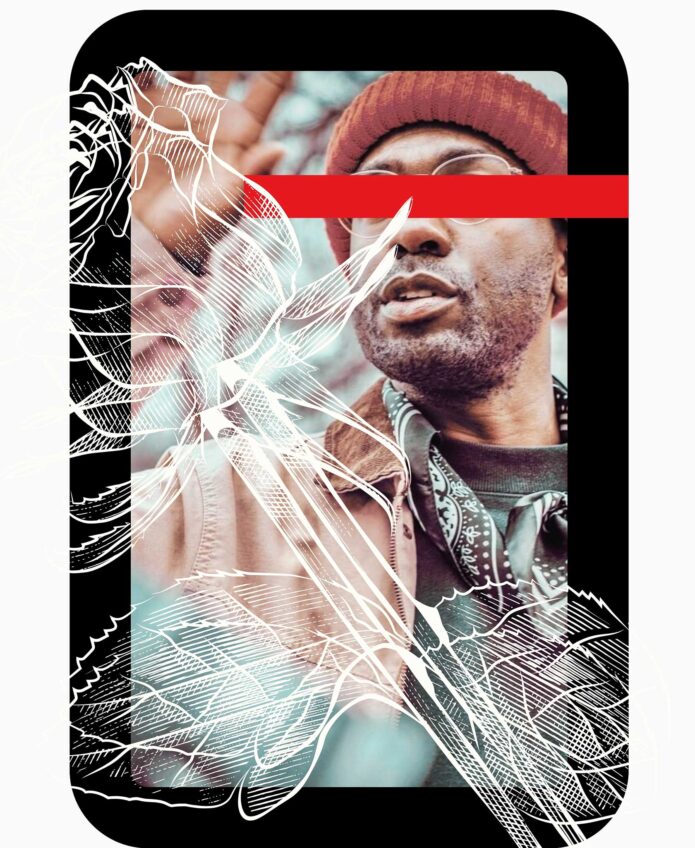

When Doug Lockwood brought “Hamlet” to the Actor’s Shakespeare Project, he already had Omar Robinson in mind for the title role. A seasoned Boston performer and Emerson grad, “Omar brings a natural intelligence and wit to the part. The two go hand in hand,” says Lockwood. The ASP production of Hamlet, playing at the Church of the Covenant through November 6, is a striking, modern twist on the classic tragedy.

Lockwood cut an hour and a half out of the show and arranged the remaining material to focus mainly on Hamlet and his family.

“I was interested in the personal relationships and the sense of claustrophobia in the family,” Lockwood says.

In one scene, Laertes and Ophelia roll their eyes at each other as their aging father Polonius settles in to give them a rambling list of advice. In another, Hamlet makes suggestive jokes with his college buddies about their female conquests. This portrait brings relatability to a play that’s set in a time and space today’s audiences have never experienced.

Robinson’s Hamlet is unlike any other. He says of the part, “Most descriptions had Hamlet as pale and morose, and I had no interest in either of those things.”

While most interpretations show a dreary, depressed heir to the throne, Robinson’s portrayal is possessed by a frenetic, comedic madness. He shouts, runs and laughs maniacally, making jokes and playing pranks. The text is all original to the Bard of Avon, but Robinson reveals a Hamlet who’s buzzing with purpose and energy.

“We’ve been handling the play with a lighter touch,” he says. “There are moments in the play of laughter and genuine love.”

In addition to the more comedic spin on Hamlet, Robinson brings a heavy awareness of his own identity as an African American man. Lockwood also took this into account when casting the show.

“The role has belonged mostly to white folks over the years,” he says. “I was interested in breaking that down. We need to see people of color in major roles more often.”

The play itself is ripe with language describing “blackness,” “darkness” and “shadow.” Robinson says, “It’s all there in the text, we’ve just interpreted it differently. This is not your grandma’s Hamlet.”

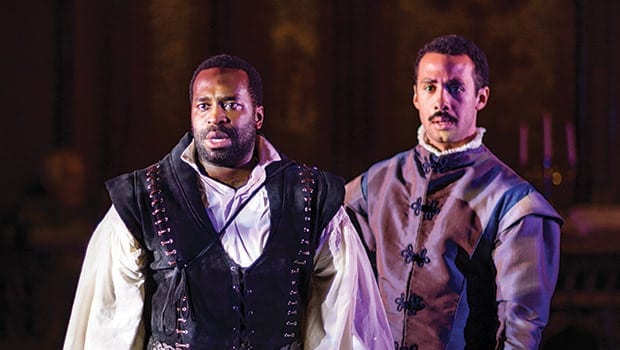

The marked character differences aren’t the only notable influences in the adaptation. Newbury Street’s Church of the Covenant serves as the show’s stage, which brings an added drama to the production. Lockwood says he didn’t realize how much of the play was centered on religion until they began working in the church. The inactive players sit on carved wooden seats behind the altar, like immobile icons judging the mortal audience. When Robinson delivers the “to be or not to be” monologue, he strolls through the aisles of the dark basilica, weaving the weight of heaven and hell into his existential musings.

For Shakespeare newcomers and Bard scholars alike, ASP’s “Hamlet” is a remarkable experience. The lush costumes, expert delivery and gothic setting transport the audience to a Denmark full of murder, turmoil and, surprisingly, laughter. Robinson says, “I think there’s something for the purist who sees what ‘Hamlet’ should be, and for the modern audience who sees what ‘Hamlet’ can be.”