After the late Martin Luther King Jr. settled in for his doctoral studies at Boston University in the fall of 1951, one of his priority non-academic tasks was to make three vital contacts in Roxbury.

The first one, made on the advice of his father, Daddy King, was to the Howland Street residence of the late Rev. William H. Hester and his wife, Beulah, a prominent social worker. Dr. Hester was an old friend of Daddy King’s and longtime pastor of the Twelfth Baptist Church, one of the city’s most prominent churches. Thus began a long relationship among Dr. King, the Hesters and the Twelfth Baptist Church. King became a “preaching regular” at old Twelfth church during his Boston University days. After his emergence to fame, whenever he came to Boston, he would usually telephone the Hesters or visit Twelfth Baptist if his schedule allowed. Although he had preaching appointments at several other black churches, he always considered Twelfth Baptist his “Boston home church.”

The second vital contact was Mary Powell, then part-time secretary of Twelfth Baptist Church and special graduate student at the New England Conservatory of Music. Mary lived on Greenwich Street near Douglass Square at that time. She was married to a relative of Dr. Benjamin Mays, was a native of Atlanta, was a friend of Daddy King and Ebenezer Church and knew all the King children. It was Mary Powell who played Cupid in bringing Martin and Coretta Scott together — right here in Boston.

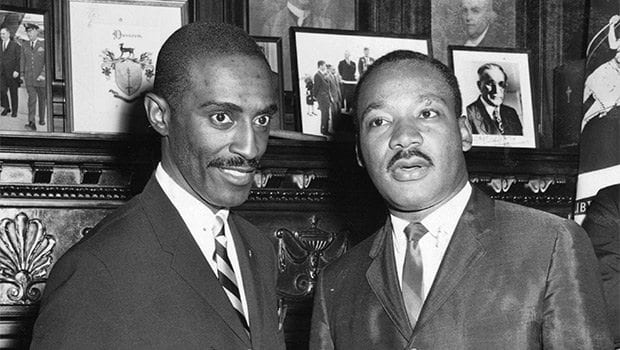

Dr. King speaks in Boston.

The third person, also a native of Atlanta, was Mrs. Barbara Wright, a retired school teacher and friend of the Senior King family. She had moved to Boston and had become active as a religious educator at Twelfth Baptist Church and in the city’s weekday school program. Mrs. Wright lived on Rockland Street and later on Dale Street. She knew Martin Jr. since his birth. Martin kept close contact with her from his student days into his famed career whenever he came to the Boston area.

When Dr. King preached at Twelfth Baptist Church in 1951, I was a seminary student and had just commenced my duties as a minister to youth. We became respected colleagues and friends.

During his commuting period as pastor at Dexter Avenue in Montgomery and the wrapping up of his dissertation responsibilities at Boston University, Martin maintained close ties with his “Twelfth Baptist connections.”

In the late Spring of 1954, when all of his University obligations were completed and he was preparing to finalize his academic stay in Boston, he preached a sort of departure sermon at Twelfth Church. At the close of the service at old Twelfth, Dr. King and his wife, Coretta, stood outside old Robert Gould Shaw House on Windsor Street having casual parting conversation with me. “M.L.” asked if I would consider coming to Montgomery to serve as his minister of youth. My northern orientation made me answer in the negative. Little did I dream where his future would lead him. I remained in Boston and as Martin Luther King Jr. emerged on the national scene, I became senior pastor at Twelfth.

In my role as senior minister of Twelfth Baptist and as a member of the state Legislature, I continued to have contact with Dr. King and provided personal services to him on his many visits to the city.

One of my greatest joys was to be able to join the planning of his great march on Boston in April 1965, and to join with my two black legislative colleagues, Royal Bolling Sr. and Franklin W. Holgate, to pass the bill that invited Dr. King to address a joint session of the Massachusetts Senate and House of Representatives. This was his first invitation to address any legislative assembly in the nation.

Dr. King and the Poor People’s Campaign of 1968.

On the occasion of his tragic assassination, I was sent as a delegate of the governor of the Commonwealth to attend his funeral in Atlanta, which I attended along with Senator Edward Brooke.

Later I was proud and privileged to be a part of the legislative action that helped make January 15 a holiday in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Four profound convictions of Dr. King were expressed and apparent in his early days in Boston in the ’50s. They later developed as major planks in his proclamation to the nation and to the world.

They are as follows:

First, as a Christian minister, he felt that God had revealed himself to us in Jesus Christ — and Jesus Christ had given to humankind two of the greatest tools to bring peace and to make the world a better place to live in — love and nonviolence, which were interwoven. He emphasized that “love is the most endurable power in the world …and the most potent instrument available in mankind’s quest for peace and security.”

Secondly, a conviction that immoral structures set up in America were destroying the potential of black young people. He explained them as the “spiritual emptiness and the spiritual evil of contemporary society.” He challenged young people to oppose those structures and free themselves to become “the best of whatever you are.”

Thirdly, Martin was convinced that the nation was treating a certain segment of its people as something less than human and that until it corrected this, the nation would be in trouble. He said, “man must never be treated as a means to the end for the State, but always as an end to himself.”

The fourth great conviction that was expressed by Martin in his Boston days and which became the trigger issue that led to his assassination, was his universal concern — his expressed objection to America’s bloody role in Vietnam. In very simple terms, Dr. King said, “All life is interrelated. We are all caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied into a single garment of destiny. We are made to live together because of the interrelated structure of reality… We aren’t going to have peace on earth until we recognize this basic fact of the interrelated structure of all reality.”