Cholesterol gets a bad rap. But actually it’s one of the good guys. Your body could not survive without it. Cholesterol is a major component of the walls of cells, offering support as well as protection from unwanted invaders. It is a key component in several hormones, including estrogen, progesterone and testosterone. There’d be no vitamin D without cholesterol.

The liver makes most of the body’s cholesterol. In truth it makes enough for all the jobs it has to accomplish. Contrary to a commonly-used term, cholesterol is not “bad.” Nor is it “good.” There’s only one cholesterol. It’s actually a victim of circumstance. Because it is a waxy, non-soluble substance, it has to travel in the bloodstream on protein carriers called lipoproteins, which are named according to their density. LDL, or low density lipoproteins, escort cholesterol to the cells, while HDL or high density lipoproteins, clean up the excess leftovers and return them to the liver for disposal.

LDL’s biggest cargo is cholesterol, but it transports triglycerides and other lipids as well.

Here’s how cholesterol gets its bad rap.

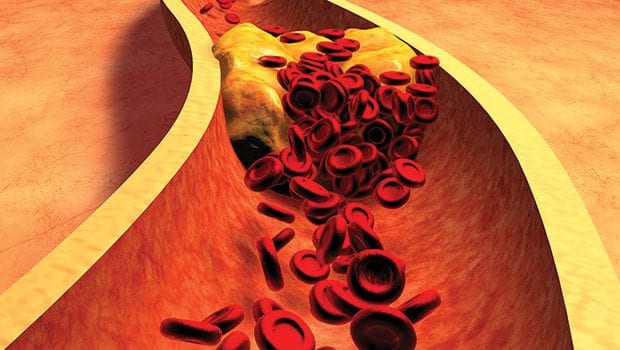

The LDL particles, especially when dense and small in size, can cling to the walls of arteries causing a blockade that can eventually prevent the passage of blood and nutrients. Because cholesterol is a part of this transit system, it gets most of the blame for forming a plaque called atherosclerosis.

It is this plaque that is associated with heart attacks, strokes and peripheral arterial disease.

The LDL does not have affinity for a particular artery. All arteries — regardless of their location — are fair game. The reason it is so strongly linked to heart attacks is because of the devastating outcome. Heart disease is the number one killer in this country.

Author: Ernesto ArroyoPradeep Natarajan, M.D., M.MSc specializes in preventive cardiology at the Massachusetts General Hospital Corrigan Minehan Heart Center.

Stats

High cholesterol is common. “No race is spared,” said Dr. Pradeep Natarajan, who specializes in preventive cardiology at Massachusetts General Hospital. “But risk factors may vary among groups.” According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one out of every three adults has high cholesterol. Half do not get treated and two-thirds do not have it under control

People tend to ignore conditions that do not directly affect their daily activities. However, cholesterol is not to be ignored. It is linked to two leading causes of death. It can precipitate kidney failure if arteries leading to the kidney are attacked and it can result in amputation if the legs are afflicted.

Testing

High cholesterol is silent. Similar to high blood pressure, you don’t know you have it unless you are tested. The recommended test is called a lipid panel, which measures total cholesterol, HDL, LDL and triglycerides. Generally, desired readings are less than 200 for total cholesterol; more than 40 for HDL; less than 100 for LDL and less than 150 for triglycerides.

The results are not always that clear-cut. Total cholesterol could test as normal, but include higher than desired LDL. To get a better look, some health providers perform additional calculations to determine one’s risk of heart disease more accurately. For instance, the cholesterol to HDL ratio (chol/HDL) is considered a better risk predictor of heart disease. A number below five is acceptable, according to the American Heart Association.

Screening should begin at 20, according to Natarajan, with subsequent testing every four to five years for those of low risk and those who test normal. People of high risk, such as those with a genetic disorder (hypercholesterolemia), or those with diabetes or heart disease should be tested more frequently. The exact screening schedule is based on individual circumstances.

At one time a 12-hour fast (no food or liquid, just water) was required before screening. That rule has been somewhat relaxed recently. However, a meal high in fats just before the test can artificially raise the triglyceride levels.

Prevention and treatment

With the exception of a genetic predisposition to the disorder, high cholesterol is largely preventable. The oft repeated foursome applies here: exercise; a healthy eating plan of fruits, vegetables, whole grains and healthy fats; weight control and abstinence from smoking When first diagnosed with high cholesterol, change in lifestyles is first in order with one exception. “An LDL greater than 190 requires medication,” said Natarajan. “That’s the top 95th percentile.” That means that the LDL is on the high end and poses a risk for cardiovascular disease.

If lifestyle cannot control cholesterol levels, medication, such as statins, niacin and fibrates, is prescribed. Healthy lifestyles, however, remain integral to treatment.

New guidelines

The medical profession has made a recent major shift regarding the effect of diet on high cholesterol. After years of warning consumers about eating foods high in cholesterol, such as red meat or eggs, it’s been found that food actually contributes little to the body’s cholesterol. This warning might have backfired. “We told people not to eat any fat,” said Natarajan, “but they continued to eat refined carbohydrates.” Unfortunately, one bad habit replaced another. Sugar-sweetened beverages and foods like white rice can produce cholesterol and triglycerides.

The modified warning does not apply to all fats. Trans fats are still taboo. Unsaturated fats, such as those in tree nuts and salmon, however, are recommended.

Another shift centers on the risk of a cardiovascular event, such as a heart attack or stroke, and the use of statins. For years the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute presented a self-assessment tool that, depending on answers regarding blood pressure, cholesterol, smoking, age and gender, estimated a respondent’s risk for a heart attack within 10 years. A risk exceeding 10 percent raised a red flag.

In 2013 the AHA and the American College of Cardiology revised the test by adding the risk factors diabetes, diastolic blood pressure and race. They changed the 10-year risk estimation to a composite of both heart disease and stroke with a cutoff of 7.5 percent.

The change has not resonated favorably among all cardiologists. While the test still applies to people with known risk factors for heart disease, it now advises a group of seemingly healthy people to consider statins based only on age and race. For instance, the ACC/AHA guidelines suggest that African American females aged 70 and older with no listed risk factors “should be on a moderate to high intensity statin.” According to a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, this change would increase the number of people eligible for statins by roughly 13 million people.

Regardless, Natarajan sees some advantages to the revised tool. It now includes race as a factor. The previous assessment tool stemmed from findings from the Framingham Heart Study, which included no people of color. “It opens up an avenue of discussion,” he explained. “Does this model fit my patient in front of me? At what point should we consider statins?”

There is still much to learn about cholesterol. It is indeed a complex compound. What we do know is that it tends to travel in bad company — high blood pressure, smoking, obesity, diabetes and unhealthy diet. The good news though is that when you take measures to tackle cholesterol through healthy living, you take on the others at the same time.