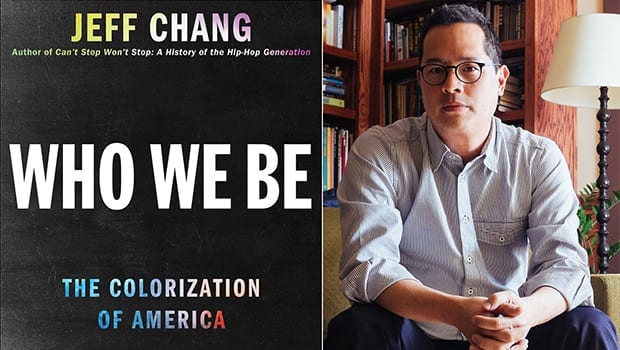

Jeff Chang is a new sage thinker with his finger on the pulse of American culture. His first book, the critically-acclaimed Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation, collected a cornucopia of honors, including the American Book Award and the Asian-American Literary Award.

Next, he edited Total Chaos: The Art and Aesthetics of Hip-Hop, an anthology of essays and interviews. Here, he talks about his latest opus, Who We Be: The Colorization of America, nominated for an NAACP Image Award in the Outstanding Literary Work – Non-Fiction category.

Don’t let yourself be dissuaded by the grammatically-incorrect title, or its Ebonics chapter headings like “I Am I Be” and “What You Got to Say?,” for the actual text isn’t written in inscrutable slang as implied, but rather makes a most articulate analysis of the evolution of American society from the March on Washington to the present.

Kam Williams: You used to just write about hip-hop. What inspired you to expand your focus for this book?

Jeff Chang: When I finished Can’t Stop Won’t Stop, I realized that the big hole was in talking about all those who had influenced me during my intellectual awakening, during the mid-1980s and into 1990s. These were people from the generation that fell between the gap of the Civil Rights Generation and the Hip-Hop Generation — teachers and thinkers like Gary Delgado and Ron Takaki and Gloria Anzaldua, writers like Ishmael Reed, Ntozake Shange and Jessica Hagedorn. They helped to theorize multiculturalism, and their ideas carried us through the culture wars.

KW: Why did you decide to examine the evolution of American culture over the last half-century?

JC: I guess every project has been a little autobiographical — this is the era that I have lived through. And now that I teach and mentor, I am always surprised and a little sad at how little my students know about what people their age did during the 1980s and 1990s. We weren’t silent. They hear endlessly about the proud brave youth of the 1960s and even the 1970s, but not much history has been done on those who came afterward. In part, this is a function of demographics — we are the shadow generation between the so-called Boomers and Millennials. In part, ours is not a history of glory and victory. When it comes to racial justice, it’s been quite the opposite. It’s not a story with a happy ending.

KW: Where do you envision America to be a half-century from now?

JC: I’m less successful at predicting than I am at reading history. I do write from a sense of urgency, though. I worry that if we don’t move toward a consensus for racial justice, that we’ll instead continue the current trends of re-segregation and end up with a more rigid, insurmountable racial caste system in 2042. That would be a horrible outcome for everyone, including whites.

KW: Do you think you have a unique perspective as a Chinese/Hawaiian- American?

JC: I’ve been blessed to come from a background in which my family has intermarried with every race and culture imaginable. My family looks a lot like President Obama’s, but much bigger. I suppose I look at the society I’m living in the way I look at my family. Because we are family does not mean there aren’t problems, but we owe it to each other to keep on talking, to try to work them out. This may make me a bit Pollyanna-ish, but you gotta believe in something, and every belief comes from somewhere, and that’s mine.

KW: Who We Be reminds me of Marshall McLuhan’s The Medium Is the Massage [not his famous essay The Medium Is the Message] which was a dizzying mix of essays, asides, aphorisms, photos and drawings. Are you familiar with that book?

JC: I am! Dizzying was exactly the right word. From the beginning I wanted the book to be visual — in the writing and in its content and presentation. McLuhan pointed out in the mid-’60s, that we were now living in a mixed-up culture where visuality was much more important. The word “colorization” comes from TV, and this is also happening right at the time McLuhan and Fiore are making their book. So, in a lot of ways, I was trying to recognize that history, while merging it with the history of the representation of people of color in the post-civil rights era.

KW: How would you describe your approach to cobbling together the content you included in your book?

JC: The organizing metaphor was seeing — how we see race. I knew I had to move in this direction after Can’t Stop Won’t Stop, and I had some elements — Morrie Turner’s cartoons and his amazing life story, on the one hand, and the street art of the Obama presidential campaign, on the other. Greg Tate, Lydia Yee, Roberta Uno, Vijay Prashad and others hit me with other key pieces that helped to shape the narrative. And as I was finishing the book, Vijay Iyer hit me sideways with his insight about listening versus seeing race. He made me understand that jazz and soul and blues are of an earlier period in which listening was central. Hip-hop comes up in an era of seeing — and so it gets complicated.

KW: What message do you hope people will take away from the book?

JC: That we need to have a real conversation about race that does not try to ignore the legacies of discrimination, debasement and inequity. And we need to transform the culture of violence that continues to lead us in each generation to have to explosively protest the way that bodies of color, often specifically black bodies, are targeted and contained. I think the best way for us to approach this is to recognize and name re-segregation as we see it, and, through cultural interventions, push toward a new consensus for racial justice.

KW: What do you make of the nationwide demonstrations in response to the failure of the grand juries to indict the police officers in the Eric Garner and Michael Brown cases?

JC: They are among the most sustained and widespread protests against state violence against African Americans in history. And they are being organized and moved in a decentralized way by thousands of ordinary Americans — mostly youths, mostly women. There are no central leaders, despite the media’s focus on some older charismatic men, and that makes them impossible to stop. They give me clarity about my work and they give me hope that we might be in a transformative moment.

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Cagen-Luse_Men-at-store-e1713991226112-150x150.jpg)

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Cagen-Luse_Men-at-store-e1713991226112-848x569.jpg)