Shakespeare on the Common

‘King Lear’ will be performed through August 9

The Commonwealth Shakespeare Company opens its magnificent production of “King Lear,” on stage at the Boston Common through August 9, with a stark prelude.

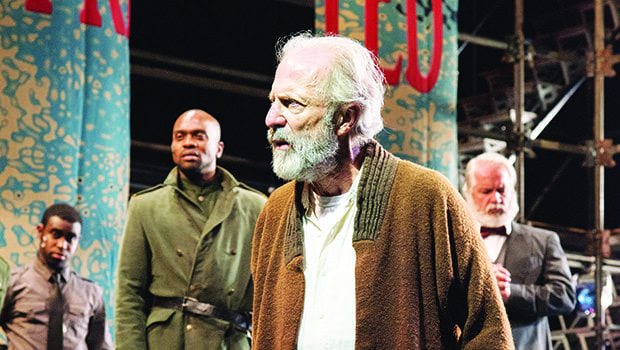

King Lear — distinguished Boston actor Will Lyman — is seated on a throne. His three daughters, dressed in black, join hands and circle him in a dance. At first, the king and his daughters smile. But then Lear’s face registers horror as his daughters bind and blindfold him.

Lear awakens from this nightmare. But the reality he wakes up to is no better in Shakespeare’s tragedy, the Commonwealth Shakespeare Company’s choice for in its 20th annual production of “Free Shakespeare on the Common.”

As the play begins, Lear, intending to retire, prepares to divide his kingdom among his daughters so that “future strife/May be prevented.” But he demands that each daughter vie for her portion of his realm by pledging her love. Bad idea.

Goneril and Regan outdo each other in their claims of devotion; but Lear’s youngest sister, Cordelia, refuses to take part and simply asserts the love due to a father. Enraged, Lear casts her out along with his loyal friend, the Earl of Kent, who protests Cordelia’s banishment. Lear soon finds himself homeless, penniless and mad after Goneril and Regan refuse to house him and his rowdy band of men.

Running about three hours including intermission, this spellbinding production is faithful to Shakespeare’s words and delivers in its full strength one of the greatest plays in the English language. Directed by Steven Maler, the company’s founding artistic director, the production encompasses the play’s humor and horror, its sublime beauty as well as wit, and its moments of redemptive grace amid disaster.

Superb performances and staging make King Lear’s turbulent journey from blindness to wisdom gripping from start to finish.

Lyman, a handsome man often cast as a romantic lead, brings depth and vulnerability to his role as an aging king who loses all by being blind to those worthy of trust, and by trusting those who betray him. Lyman also brings to his role a gifted actor’s ability to draw the best from those around him by not overplaying his part. Lyman’s rendering of Lear is commanding in its humanity. His Lear blunders, suffers, rages and grows wise not as a standalone figure, but, just as Shakespeare wrote the part, through his interactions with others. Lyman and his fine fellow cast make these relationships come alive, generating intense on-stage chemistry.

Complementing the 13 actors in lead roles is the company’s ensemble of young actors, who perform as attendants, soldiers, knights and courtiers.

Mickey Solis excels as Edmund, the scheming illegitimate son of the Duke of Gloucester, who convinces the duke that Edgar, the duke’s legitimate son, plans to kill him for his money. Solis portrays Edmund as an irresistible villain, exuberant in his unbridled ambition to gain wealth “If not by birth…by wit.” His Edmund faces the audience to confide his plans, and as the duke reads the letter Edmund forged as evidence of Edgar’s plan, Edmund silently mouths the words, sharing his triumph with us. Solis is equally convincing in dying Edmund’s redemptive moment as he says, “Some good I mean to do.”

Equally riveting is Jeremiah Kissel in the role of Edmund’s counterpoint, the banished Kent, who disguises himself as a ruffian to continue serving the king. He joins Lear’s band of men and handily beats up Goneril’s servant Oswald for disrespecting the king. Kissel’s Kent is grave, down to earth and ready to fight, embodying Lear’s description of him, “He’s a good fellow, I can tell you that; He’ll strike, and quickly too.”

At the forefront of the loyal camp is the Fool, who taunts the king for his folly. After a few moments of cabaret-style mugging, Brandon Whitehead fully inhabits this mammoth role.

Like the characters in Samuel Beckett’s tragicomedy “Waiting for Godot” who rely on humor to survive their bleak existence, Lear and his Fool wear bowler hats as they trade insults.

Katherine O’Neill works such telling details into her expressive costumes, which vary from the shabby professorial garb of a homeless Lear to the sisters’ militant leatherette skirts and boots. The French troops that Cordelia marshals to defend her father sport natty white military jackets. As Lyman’s Lear howls, mad with grief, he wears a wire wreath that evokes another soul crazed by loss, Ophelia, Hamlet’s abandoned love.

Scenes vary from a court to a storm-whipped heath; rapid-fire mood shifts within scenes can turn such events as a rollicking gathering into a brawl. The fast-moving production keeps pace with the play’s emotional momentum through agile acting as well as nimble staging.

Spare geometric sets by Tony award winner Beowulf Boritt underscore the tragedy’s complex power plays and allow fluid scene changes that render the play’s moment-by-moment revelations and turns of fortune.

A throne stands on a raised platform that doubles as a cliff. A row of vertical fabric panels is a backdrop that actors pull down one by one to expose new characters or change a setting. They rip down the curtains just as events tear down Lear’s false grasp of his world along with his hold on power, wealth and sanity.

Production value

Also serving to illuminate each scene’s emotional tenor are subtle lighting by Peter West and deft sound design by Colin Thurmond, which incorporates evocative electronica passages by Gabriel Prokofiev (grandson of 20th century composer Sergé Prokofiev). But when the time comes to conjure a shattering storm, they pull out all the stops to create a multisensory assault of sound, light, and showering rain that coincides with Lear’s moment of utter helplessness and awareness.

Choreography by Yo-el Cassell and fight direction by Jeremy Browne contribute to the production’s lively pace and articulate use of body language, not only for fights but also to reveal character.

As Goneril, the elegant and statuesque Deb Martin pours herself into her vicious role. With her chiseled profile and pulled-back hair, she towers over her husband, the Duke of Albany. As the duke, Mark Soucy persuasively grows in authority as he takes action to counter the murderous plot Goneril and Regan share with Edmund.

Jeanine Kane also is well-suited for her role as Regan. With her soft features, Kane looks the part of the good daughter that Lear believes her to be, but she comes to match her relentless husband, the Duke of Cornwall (a convincing Maurice Emmanuel Parent), in cruelty.

Holding her own against her monstrous sisters is the gentle but strong Cordelia. However, rather than expressing tenderness, Libby McKnight injects her Cordelia with combative energy, a choice that stiffens her portrayal.

As Edgar, Ed Hoopman morphs from dorky good son into a man on the run. Disguised as a beggar, Edgar escapes to the windswept heath where he encounters Lear. Cast off by Goneril and Regan, the king has become their prey. Accompanied only by Kent and the Fool, the defenseless and near-mad Lear is moved by pity for the beggar, and shields him from the storm. Lear tells Edgar’s quivering, babbling figure, “Thou art the thing itself: unaccommodated man is no more but such a poor bare, forked animal as thou art.”

Ending with a scene as stark as its start, the production closes with a bewildered Edgar alone on the stage, looking out at the audience.