Much has changed in the 25 years since the Stewart case. Some things haven’t

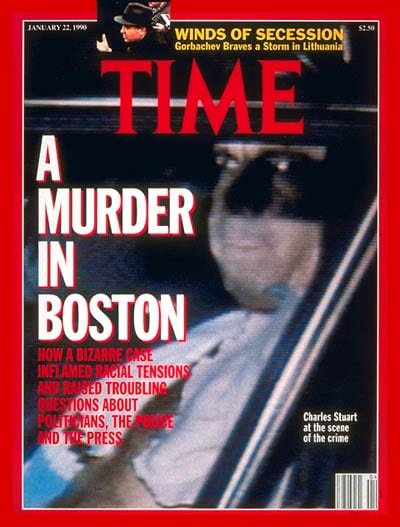

One of Boston’s more shameful chapters opened 25 years ago with a frantic call to police dispatchers from Charles Stewart, who claimed a black man shot him in the stomach and his wife in the head.

That call, along with the vague description of a 6-foot tall black man wearing a black sweatsuit set in motion a weeks-long dragnet that ensnared black teenagers and men of all shades, sizes and descriptions. While violations of blacks’ 4th Amendment protections against illegal search and seizure were routinely violated by police in the ’80s, the volume of invasive stops and searches and the raw aggression visited on black youths during those weeks left an indelible mark on a generation of black Bostonians.

Two months later, when Charles Stewart took his life, jumping from the Tobin Bridge, the revelation that he had shot his own wife and himself in the stomach, fabricating a take of a robbery ostensible to collect life insurance added salt to the wounds of a black community that had already been through a punishing ordeal of heavy-handed policing and a news story that cast the Mission Hill neighborhood and the black community in a decidedly negative light.

Stewart’s blame-a-black man ruse, though ultimately unsuccessful, was yet another black eye for Boston, a city still marred by the racist legacy of segregated schools and fierce white opposition to busing. The denouement of the case included a healthy helping of navel-gazing in the media and, most promisingly, a special commission, headed by attorney James St. Clair, convened to examine police practices.

The report from the St. Clair Commission focused heavily on the need for a civilian review board to investigate allegations of police misconduct. The commission found that 50 percent of complaints against the police were filed by African Americans (then 26 percent of the city’s population) and 9 percent from members of other minority groups.

“Given the Internal Affairs Division’s (“IAD”) failure to routinely provide thorough and timely investigations of alleged misconduct, and the fact that the Department sustains less than 6% of complaints against officers, it is no surprise that the overwhelming majority of community residents we spoke to have little confidence in the Department’s ability or willingness to police itself,” the report reads

Fast forward 25 years, and some things have changed. The Mission Main housing project where Stewart killed his wife underwent a $127 million redevelopment and is now a mixed-income community where college students and young professionals live next door to the remaining subsidized units.

And the Police Department did create a Civilian Ombudsman Oversight Panel, but, as the Banner reported last year, it hears few cases.

Most of the men who were stopped, searched and otherwise humiliated by the ham-fisted detectives during the weeks after Stewart’s shooting are, like this reporter, too old to feel the brunt of unfair police practices, but teens interviewed by the Banner and the ACLU complain of an ongoing pattern of civil rights abuses.