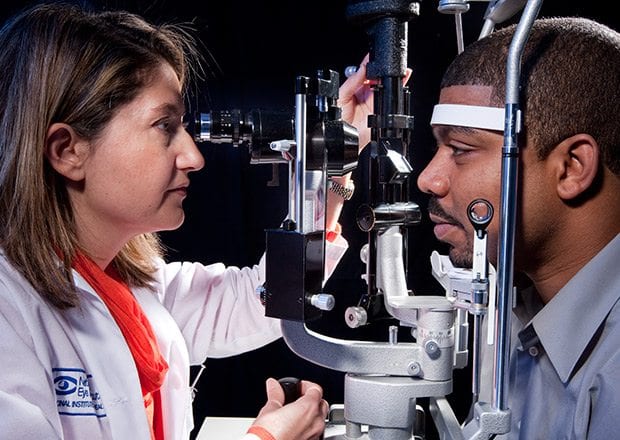

Jean-Bernard Charles, M.D., M.P.H.

Ophthalmologist,

Whittier Street Health Center

Joseph Carter (not his real name) overlooked his increased thirst and frequent urination. His blurred vision and those pesky floaters that sometimes blocked his vision got his attention, though. The report from the ophthalmologist was a rude awakening. “You are diabetic,” his doctor said. “And you’ve had it (diabetes) for a long time.”

That was news to Carter. There was no history of diabetes in his family. Nor did he recognize the symptoms. “It never clicked in my brain that I was drinking more water than usual,” he explained. Besides, he reasoned that he was young and healthy. Nothing could possibly be wrong with him.

Carter, 57, had diabetic retinopathy, which causes damage to the blood vessels in the retina. He is not alone. Up to 50 percent of people who have had diabetes for 15 years or more have diabetic retinopathy, according to Dr. Jean-Bernard Charles, an ophthalmologist at Whittier Street Health Center. The retina acts like the film in a camera and converts images to electric signals and sends them to the brain. In other words, one cannot see without a healthy retina.

Diabetic retinopathy is one of the leading causes of blindness in this country, according to the National Eye Institute. It is estimated that more than 4 million people with diabetes are afflicted.

By the time of his diagnosis Carter’s condition was at the advanced stage. The fragile blood vessels that formed in the retina had ruptured. That explained the bits of blood — what he called floaters — obscuring his vision. The blurring was a result of swelling in the macula, a small area in the center of the retina. The macula is responsible for pinpoint vision.

Diabetes retinopathy is often progressive. It starts with swelling in the retina’s tiny blood vessels. Eventually the vessels are blocked, depriving the retina of oxygen. New blood vessels form but are so delicate they can burst with just a sneeze. The rupture results in inflammation and scar tissue and if left untreated can cause retinal detachment.

The condition is largely preventable, especially when blood glucose levels are controlled. “We recommend a yearly screening eye exam,” explained Charles. Screening can often detect the condition even if there are no symptoms. In some cases, when found and treated early, vision can be restored, said Charles. Otherwise, treatment merely prevents progression of the condition. Sight lost may not be regained

When Carter reported to his district clinic in Trinidad he discovered that diabetes was not his only problem. He had high blood pressure, high cholesterol and his kidneys were functioning at 50 percent capacity — all consequences of diabetes. Symptoms for all these diseases were silent. His vision was the only giveaway that a very serious disease was lurking.

Carter eventually underwent a vitrectomy, a surgery to remove the blood and scar tissue in the retina. As is usually the case, both eyes were affected. Although the vision in his left eye was worse, Carter elected to have the surgery in his right eye. “The left eye was too bad to salvage,” he reasoned. “I wanted to save the vision in my right eye.”

Things were going pretty well, according to Carter. Although his vision was poor, he could see well enough to get around. All that changed one day when he went to retrieve something from the refrigerator. He accidentally hit a glass bottle that fell and shattered.

Although he cleaned up the pieces his poor eyesight caused him to miss a fragment or two. Carter, who was barefoot at the time, stepped on a piece of glass, which started a cascade of misfortunate events.

He cut his right foot. The wound eventually healed with antibiotics and stitches. But two years later an ulcer appeared. “It would not heal properly,” Carter explained, even after two years of constant treatment. Finally, In January 2013, he had his right leg amputated below the knee.

About 60 percent of non-traumatic lower-limb amputations among people aged 20 years or older occur in people with diagnosed diabetes, as noted by the American Diabetes Association. In 2010, that accounted for roughly 73,000 amputations.

The good news is that his leg healed well. In July of last year he received a prosthesis and is able to walk independently with a cane. “It gives me a sense of stability and confidence,” he explained, and allows him to take a cab to his appointments at Whittier Street Health Center without assistance.

If he could turn back the hands of time, Carter said he would make a few changes. “I would have checked for diabetes. People should start at age 20 since it can attack at any age.”

Every six months he gets his eyes checked at Whittier. The doctor has a good report. “It’s clean and clear,” the doctor says, which means that there is no blood buildup in the retina.

Carter says he wants to keep it that way. He knows his vision cannot improve, but he wants to save what he has left. He knows the key to success.

“I keep my sugar under control,” he said.