It’s a commonly-seen phenomenon: An aging relative or friend becomes slower at processing bills and calculating tips, or finds it increasingly difficult to decipher a medical bill; arithmetic errors in the checkbook register make it all the harder to balance the account at the end of the month.

This is an expected part of aging, but such difficulties can also be warning signs of a financial competence decline that makes seniors more vulnerable to abuse by caregivers, scam artists or family members granted control of an elder’s finances.

While the term “abuse” may conjure up visions of physical injury or neglect, the most common form of elder abuse is financial exploitation, according to Naomi Karp, a senior policy analyst for the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s Office for Older Americans.

Karp was part of a financial exploitation panel discussion last week at the Gerontological Society of America’s 2014 Annual Scientific Meeting in Washington, D.C.

Elder financial exploitation is defined as “illegal or improper use of an older adult’s funds, property or assets” by any type of perpetrator, from close a relative to a repair contractor to a telephone swindler. It is a growing but underreported crime. Karp cited recent estimates that 5 percent of community-dwelling seniors have been victims — but that for every reported financial abuse incident, about 43 cases go unreported.

Daniel Marson, a professor of neurology at the University of Alabama-Birmingham School of Medicine, listed warning signs to watch for in aging adults, including increased slowness in processing bills, missing key details (for instance, a warning that payment is overdue), increased trouble with financial arithmetic, and decreased understanding of financial concepts such as medical insurance deductibles.

The ranks of older adults are expected to swell nationwide in the coming decades as the large Baby Boomer generation reaches their 60s and 70s. Here in Boston, following a decline between 1990 and 2000, the older adult population has been on the rise. From 2000 to 2020, Boston will see a 32.1 percent increase in the number of residents 60 and older, and a 21.3 percent rise in those 65 or older, according to projections from the Massachusetts Executive Office of Elder Affairs. Older adults are the fastest growing population segment worldwide and locally.

With this increase, more and more relatives or caregivers may be thrust into a “financial caregiver” role. For some, this may be an easy role that draws on natural abilities or money management experience. Others will lack the skills, confidence or time to do the job well. And some will use the role to rob elders of their life savings.

In Boston, the nonprofit Ethos in Jamaica Plain functions as the state Elder Protective Services agency for Greater Boston in collaboration with Central Boston Elder Services and Boston Senior Home Care.

Sandy Hovey, Ethos’ director of elder protective services, said the agency receives 160 to 200 reports of elder abuse monthly, many of which involve an elder victimized by a financial scam or taken advantage of by a family member.

Hovey did not have figures on the percentage of abuse incidents that are financial, but he said financial abuse is often intertwined with emotional or physical abuse. For instance, a grandson beat his 78-year-old grandfather when he refused a demand for money.

Even after enduring hospitalization for his injuries, the older man declined to press charges against the grandson, Hovey said, illustrating how difficult it can be to intervene in exploitation by elders’ own family members.

In other disturbing examples, Hovey told of an 88-year-old woman nearly evicted from her assisted-living residence after the daughter handling her finances pocketed her mother’s rent money, and a 78-year-old woman who received a call from a stranger who began with “Hi, Grandma,” and said he was in trouble and needed her to mail a check right away but not to tell anyone. This sort of tactic is seen quite often, Hovey said.

Family members given power of attorney have been known to secretly take out mortgages on elders’ paid-in-full homes, he said, leaving unsuspecting homeowners subject to foreclosure.

For well-meaning caretakers needing guidance, CFPB has recently published a series of “Managing Someone Else’s Money” handbooks, available for free download from the CFPB website.

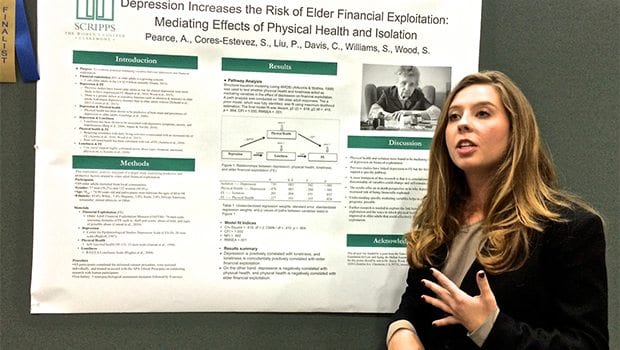

At the GSA conference, a number of researchers were on hand to explain their findings about financial exploitation.

A wide-ranging Scripps College study on risk and protective factors on elder financial abuse, to be published in 2015, identified depression as a risk factor and also found that declining numeracy skills and low financial literacy are more important predictors of financial vulnerability than education levels.

Researchers at Baylor College of Medicine described the Elder Investment Fraud and Financial Exploitation Prevention Program to educate physicians and attorneys to recognize when their older patients or clients may be vulnerable or victimized and refer them for help. EIFFE publishes a “Clinician’s Pocket Guide” with questions to ask patients or clients to gauge their financial capacity.

At the GSA conference, Baylor Professor Robert E. Roush stressed the urgency of recognizing financial exploitation, which he said can leave seniors impoverished, unable to pay for needed health care or even food.

“There’s something tragic about people working all their lives and then being targeted by scammers,” he said. “Older people flat out do not have time to earn that money back.”

For more information, see the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s information for older Americans at www.consumerfinance.gov/older-americans. For local Boston information, contact Ethos at 555 Amory Street, Jamaica Plain, 617-522-6700, www.ethocare.org/protective-services. For urgent reports outside regular business hours, call the statewide Elder Abuse Hotline at 800-922-2275.

Sandra Larson wrote this article through a Journalists in Aging Fellowship, a collaboration of New America Media and the Gerontological Society of America, with support from AARP.