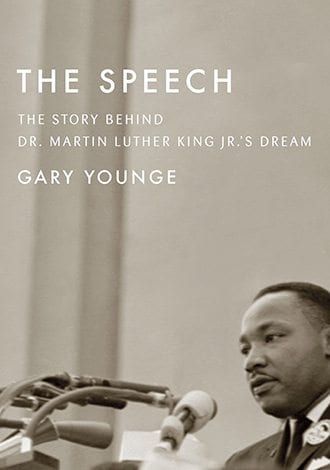

Legacy of the ‘dream’: New book studies Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous oration

In The Speech, author Gary Younge explores the history of the “I have a dream” speech.

Fifty years after the March on Washington, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I have a dream” speech stands out as the most memorable moment in the historic gathering — and perhaps in the entire Civil Rights Movement.

But the “dream” refrain that made it so famous almost never happened.

King had been using the “I have a dream” passage for more than a year before the march — including at a Detroit rally earlier that summer and in Chicago just a week before — but decided not to revisit it in Washington. Even one of his closest aides, Wyatt Tee Walker, warned him against invoking the dream that day, saying it was “trite” and “cliché.”

Instead, King based his speech on the “bad check” metaphor of the promissory note that has “come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’”

So when he approached the podium as the last speaker at the March on Washington, “I have a dream” was nowhere to be found in his prepared text. But as he closed in on the end of his speech, the famous gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, who was standing nearby, shouted out to him, “Tell them about the dream, Martin!”

It was then that King pushed aside the written text, changed his demeanor and extemporaneously went into “I have a dream.” Clarence Jones, who wrote the draft text of the speech, leaned over to the person sitting next to him, saying, “Those people don’t know it, but they’re about to go to church.

Whether King departed from his planned speech to include the “I have a dream” passage because of Jackson’s cry, or as a response to the mood of the crowd remains unknown — but the result was one of the defining moments of the 20th century.

This is just one of the many behind the scenes stories in Gary Younge’s new book, The Speech: The Story Behind Dr. Martin Luther King’s Dream, which draws on extensive interviews with Civil Rights leaders and King confidantes, including Andrew Young, James Farmer, Fred Shuttlesworth and Clarence Jones, to explore the making of King’s most famous oration and the legacy it leaves behind 50 years later.

In addition to showing how the text of King’s speech came about, Younge, a columnist for The Guardian and The Nation, also details the broader context for “I have a dream” in the Civil Rights Movement and the March on Washington — which is where some of the most fascinating historical details come out.

For instance, on the day of the March, Washington, D.C., had nearly shut down — elective surgeries were canceled, local sports teams postponed their games and the sale of alcohol was banned. Thousands of troops were deployed to the area, and the Justice Department had secretly installed a switch in the sound system that would enable them to cut off the microphone if anyone hijacked the podium.

And after his speech, only 44 percent of Americans had a favorable opinion of King, and the FBI’s assistant director for domestic intelligence called him “the most dangerous Negro of the future of this nation.”

But Younge says that much of this historical backdrop has been lost in how most Americans think about King and his speech half a century later. So instead of the radical “indictment of American racism” that once had the federal government scared, the address is today seen as “patriotic,” Younge says, so much so that even “hard Republicans would never admit to not liking it.”

The softening of King’s image — that is, the erasure of the radical aspects of his life and work — has meant that much of “I have a dream” has been “misused and misappropriated.”

One of the best examples is King’s line that people should not be judged “by the color of their skin but by the content of their character,” which is frequently employed by conservatives to oppose affirmative action and other policies designed to benefit people of color. But as he points out, King himself was a strong proponent of affirmative action — to suggest that his words meant otherwise is “ridiculous” and “unconscionable.”

“It’s a phrase used by people eager to portray racism as an egregious historical episode that’s happened and has now been solved,” says Younge, who notes that this is the same logic that was also used to undermine the Voting Rights Act in June. “They use it to say, ‘We will not take race into account, and therefore we will never take racism into account.’”

For Younge, the legacy of King’s speech is a reminder of the forgetfulness of public memory. “He said to us, ‘It’s not so useful that everybody has the right to eat at the same establishment if they can’t afford what’s on the menu,’” Younge says.

“He’s misunderstood as a guy who just wants people to be nice to each other, but when you look at his life trajectory, he’s clearly calling for an entire systemic shift.”