“Race to Incarcerate: A Graphic Retelling” illustrates exploding incarceration rates

Graphic novel adapts seminal 1999 work by the same name

Over the past four decades, the U.S. prison population has skyrocketed — jumping from about 250,000 in the early 1970s to more than 2.3 million today — so that now, the country’s incarceration rate towers above that of every other country in the world.

The story of how this happened — and the effects it has had — has been told by a number of prominent writers and filmmakers in recent years, from Michelle Alexander in “The New Jim Crow” to Eugene Jarecki in the documentary “The House I Live In.” But a new book imagines the history of mass incarceration in an entirely new way — as a graphic novel.

“Race to Incarcerate: A Graphic Retelling” is an adaptation of Marc Mauer’s seminal 1999 work by the same name, and uses text and illustrations by political cartoonist Sabrina Jones to explain how the United States became the global leader in incarceration and to highlight the impact on communities of color.

Mauer, who is executive director of The Sentencing Project and widely considered one of the country’s leading experts on the criminal justice system, says the idea for the graphic novel came from a prisoner in Connecticut who read the original version of “Race to Incarcerate,” made some comic illustrations of the text and mailed them to Mauer.

“I looked at them, said, ‘These are pretty cool,’ and sent them to my editor,” Mauer says. “She said, ‘Why don’t we turn this into a graphic novel?’”

Mauer couldn’t work with the prisoner who had inspired him — he says the logistics were too complicated — so he enlisted the help of Sabrina Jones, a longtime political cartoonist who draws for the magazine World War 3 Illustrated. Jones says that since Mauer’s original was a “rational” presentation of dense policy and data, she wanted to “add a layer of drama and emotion” to the narrative.

“My goal was to help the normal human imagination connect and empathize with the individual people who are being affected by this movement towards mass incarceration,” she says.

Jones does this by highlighting the people who have shaped — and have been shaped by — this movement toward mass incarceration, from Charles Dickens, who was an early critic of the country’s prison system, to Nelson Rockefeller, the New York governor who pioneered harsh drug laws in the early 1970s, and Kemba Smith, an activist who, as a pregnant college student, was sentenced to 24-and-a-half years for conspiracy because her abusive boyfriend was running a crack cocaine ring.

“My goal was to help the normal human imagination connect and empathize with the individual people who are being affected by this movement towards mass incarceration.”

— Sabrina Jones

Jones also follows the presidents from Richard Nixon — who declared the War on Drugs in 1971 — to George W. Bush, showing how each one contributed to the “tough on crime” movement that has bolstered the U.S.’s record incarceration rate.

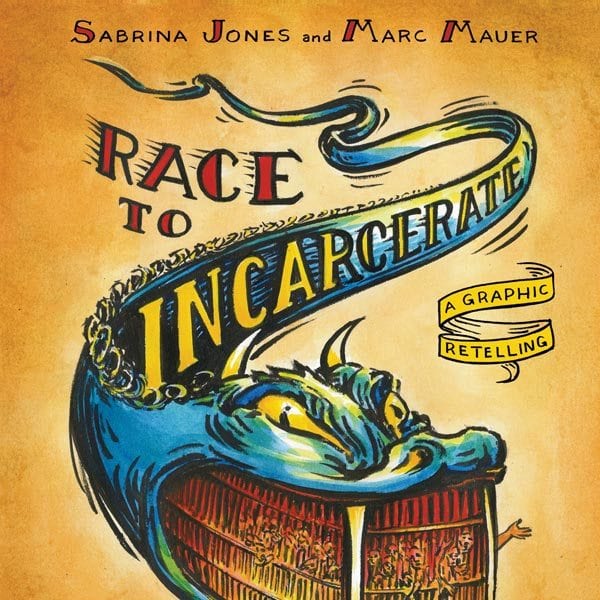

But one of Jones’ most powerful illustrations, which appears several times throughout the book, is not of a human but of a monster — a giant serpent whose long teeth cage people inside its mouth.

Jones says the inspiration for this drawing came from medieval artwork, which often portrays hell as the mouth of a beast. And in modern parlance, the serpent conveys the “monstrous” growth of the U.S. prison system and the idea that prisoners are trapped in the belly of the beast, she says.

This image also appears on the book’s cover, but with a slightly different design that Jones says mimics vintage tattoo art and lettering, “an homage to a prisoner’s art form,” she explains, “a reference to prison culture to give it a little bit of a positive spin.”

While the format of this book may be different from earlier editions of Race to Incarcerate, Mauer says his fundamental message remains the same. “There should be consequences for people who commit crimes or harm other people, but one of the problems is that we’ve come to equate those consequences primarily with incarceration,” he says. “We need a complex mix of factors to produce public safety: access to opportunity; and economic resources to deal with social problems such as poverty, substance abuse and poor schooling; and criminal justice when it’s appropriate.”

Mauer argues that the prison system has become so large that it’s robbing resources and attention from many of those other approaches.

“I think if we reverse some of those priorities,” he says, “we’d get much better outcomes in public safety, we’d have less racial disparity and we’d have fewer horrible consequences than we’re seeing today from the prison system.”