A long, long way from home: Remembering the life of musician Richie Havens

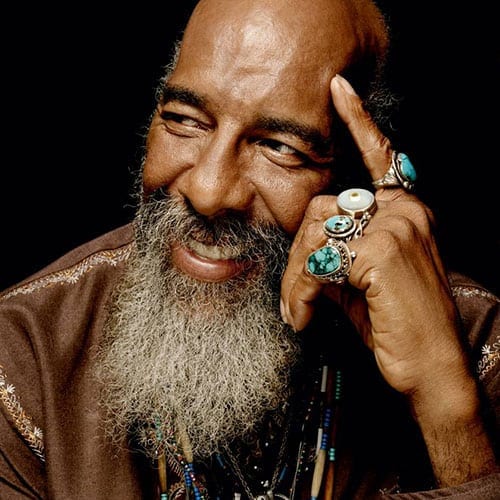

The prospect of a face-to-face interview with Woodstock icon Richard Pearce Havens was, to a degree, intimidating. Thankfully, it led to illumination, once you got beyond the turquoise rings, the flowing dashiki, the aura of serenity coupled with the avuncular manner of a sidewalk sage. Although Havens stood six-foot-three, he emitted a beatific, Buddha-like grace attuned, it seemed, to some distant music of the spheres.

Invariably, Havens’ hands caught one’s eye. Huge and enveloping, their dominant feature was the thumb. This was one of his keys to success, for the largeness of his left thumb was ideally suited to barring chords in open tunings, a technique uncommon in the early ’60s folk music circuit. Here was a signature sound: unique, percussive, an unmistakable soul shakedown, helping to launch a career which began in 1957 with doo-wop singing on street corners in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn.

In a career spanning 72 years — 1941-2013 — as an actor, activist, musician and singer-songwriter, as an educator and spokesperson for peace, love and the environment, Havens matured with one inestimable advantage: along with those of his eight siblings, his childhood was suffused with music and parental love.

Richie Havens

Family of Performers

His father, of Blackfoot Native American ancestry, crafted Formica tables. “My father was an ear piano man,” Havens recalled, “he could just hear something and play it.” Havens’ mother, employed as a bookbinder, loved to sing. Yet it was his Barbadian-born grandmother who provided the crucial link to roots. Under her tutelage, Havens was immersed in a mixed bag of Caribbean folk music, Jewish folk songs and Irish ballads.

Speaking reverently of his parents, he went back to 1904, when Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show was the rage of the nation. The show was a full-blown theatrical spectacle, a touring company of desperados and cowboys, boasting gunfights, stage robberies, a re-enactment of Custer’s Last Stand and guest appearances by Buffalo Bill and Deadeye Dick. Geronimo, the notorious Apache chieftain, was loaned from prison, recruited to play the part of the medicine man Chief Sitting Bull. Less known is sepia-tinted photograph from some time later depicting Geronimo driving with buddies in an advertisement for Cadillac.

Also part of the show was Havens’ grandfather, a horse trainer born in Montana who “joined the Wild West Show and came to New York, where he left the show.” A generation later, he explains, “my parents met in Brooklyn.”

By age 16, Havens was singing gospel with the McCrea Gospel Singers and doo-wop as a member of The Last Men. Despite these musical forays, “the ’50s was a flat line,” he claims, an era chilled as much by the Cold War as by Mother Nature, a time when Manhattan beckoned, the island being a spawning ground for folks derisively called beatniks.

A Musician in the 1960s

Gravitating to Greenwich Village in 1961, the 21-year-old Havens became immersed in a countercultural mecca of social-political-musical ferment. He began to write and perform poetry. For two years, by daylight, he was a sidewalk portrait painter, “mostly pencil, a little charcoal.” By candlelit nights, however, Havens haunted smoky dens fragranced with sandalwood and patchouli, clubs such as the subterranean Gaslight Café, Café Wha? and Gerde’s Folk City. Sundays the sandal-footed musical apprentice could be found at Washington Square Park. The Village’s countercultural ambience provided the apprentice musician an eclectic range of styles and inspirations, contributing to what would become Havens’ often plaintive trademark sound and introspective delivery. These would alternate with sudden flights of energetic crescendos, propulsive blues or flamenco flourishes with one leg slapping the floor in frenetic rhythms, eyes shut tight in a meditative trance, spirits alight perhaps.

During these early days of Camelot and the New Frontier, beehive hairdos and the occasional leopard skin pillbox hat, Havens forsook childhood dreams of becoming a surgeon. Instead, his schedule became three coffeehouses nightly, playing — and praying — for good tips when the basket was passed after 20-minute sets.

Appropriately enough, Richie Havens’ first recording, Mixed Bag, was released during America’s Summer of Love, in 1967. It was a soulful mélange reflecting an era of experimentation and skepticism — folk, blues, jazz, gospel and rock. Highlighting its militant pacifism and bittersweet realism, “Handsome Johnny” (co-written with Lou Gossett, Jr.) was counterpoised to John Lennon & Paul McCartney’s “Eleanor Rigby” and Bob Dylan’s “Just Like a Woman.” A short time later, this sage of flower power was informing Rolling Stone: “Music is the major form of communication. It’s the commonest vibration, the people’s news broadcast, especially for kids.” Within the year, these kids would turn out for the greatest love-fest ever seen on planet Earth.

The Show in Upstate NY

Although now enshrouded in an amber glow of nostalgia, Havens’ opening performance at the Woodstock Music and Art Fair was an unexpected twist of fate. “I opened Woodstock by default,” Havens reminisced late one October night in Stoughton, Mass. “I was supposed to go on as number five, but there wasn’t anyone to go on, so they convinced me to go on first. They had a lot of convincing, too, because the concert was 2 1/2 to three hours late. But they couldn’t get anybody to the field, because the road they had opened to bring the instruments and the amps and the groups was blocked. So I sat around. Eventually, they got hold of a local guy who had a bubble helicopter and since we had the fewest instruments they took my bunch of guys there first.”

“Shortly after that something happened that on one ever talks about. The Army came in. It was Army helicopters that got the bands to the stage. Not too many people know that. But if it wasn’t for the Army, Woodstock would never have happened.”

“After seven encores, I looked out over the audience and realized that this whole generation was looking for freedom and in actuality, at that point, we were exercising the freedom that we thought we needed to have. We were all doing it right there. So I started strumming my guitar and singing ‘Freedom’ and ‘Motherless Child’ came out, and then part of another song I used to sing when I was in a gospel group when I was about 16, which was ‘I Have a Telephone in My Bosom, and I Can Call Him Up in My Heart.’ And ‘Clap Your Hands.’ That was how ‘Freedom’ was made up.”

After a 2½ hour delay, Richie Havens was the first musician onstage at Woodstock.

Life After Woodstock

In 1969, Johnny Carson invited the loquacious ex-Brooklynite to perform on The Tonight Show. Havens received such a rapturous, indeed tumultuous, ovation, a bemused Carson invited him to perform the following evening. It was only the second time in the show’s history that a return invitation would be extended. Despite commercial success and critical acclaim, Havens never relinquished a critical eye on “politricks,” a notion he discussed with Jamaica’s The Wailers (Bob Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer) in Kingston just prior to his Woodstock appearance.

Following Woodstock, Havens’ acoustic alchemy turned to freewheeling interpretations and collaborations tinged with cosmic consciousness and occasional indignation, which, as writer George Sand once observed, is the highest form of love. After his immensely successful rearrangement of George Harrison’s solar benediction, “Here Comes the Sun,” Richie joined The Who’s stage performances of the world’s first rock opera, Tommy. Three years later, he would play the lead role of Othello in Catch My Soul, a rock-and-roll interpretation of Shakespeare’s classic tragedy. Havens then co-starred with Richard Pryor in Greased Lightning, the balladeer joining the comedian in retelling the story of Wendell Scott, the first African American to obtain a NASCAR racing license. Inspired by Egyptian President Anwar Sadat’s unprecedented visit to Jerusalem in 1978, the ever-flexible social activist released “Shalom, Salaam Aleichum” which became a No. 1 hit in Israel.

For the next three decades, Havens flourished as an Aquarian ambassador in kinetic touch with his Native American ancestry, an awareness that transforms the deceptive simplicity of “The Indian Prayer” on Mixed Bag II into an experience of spiritual transcendence. This heightened ancestral awareness culminated in his decisive role as a founding member of the Native American Music Awards, the first of which aired on April 22, 1998. Thirty years after his inspirational August 15, 1969, helicopter ride over Max Yasgur’s dairy farm, when some 500,000 festival goers below appeared as a dayglo mosaic of humanity, Havens released his autobiography, They Can’t Hide Us Anymore.

For this musical Brahman, traditional indigenous reverence for the environment naturally inspired ecological activism. He became a co-founder of the North Wind Undersea Institute, a hands-on learning center headquartered in a Victorian sea captain’s mansion on City Island in the Bronx. Moving from conversationalist to advocate, Havens explained: “Growing up, I learned that all the things we have labeled as social issues, such as homelessness, hunger, drugs, joblessness, are in fact environmentally based issues. They really are not social issues. The ramifications of being in any of these places is social, but the problem comes from the earth. To me, such issues are part of the environmental awareness that we should have. Today it is called environmental justice.”

At President Bill Clinton’s Environmental Inaugural Ball on Jan. 20, 1993, Havens serenaded the audience with reminders of Tibetans under Chinese occupation; closer to home, he admonished revelers “to explain the touch, the feel, the fabric of our lives.” Many television viewers were already familiar with his railroad Americana for Amtrak, Havens’ barely audible background vocal reminding us there’s “something about a train that’s magic.” These wistful vistas reemerge in Havens’ deferential interpretation of The Band’s “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” songwriter Robbie Robertson’s elegy for the closing months of the Civil War. “In the winter of ’65 …”

Soundtrack For A Revolution, released in 2009, is an invaluable study of the modern Civil Rights Movement. For this video documentary, Havens sings “Will the Circle Be Unbroken?” A half-century removed from his youthful stint with the McCrea Gospel Singers of Brooklyn, his rendition underscores commentator Coretta Scott King’s belief in “the indispensable role that songs of rebellion and hope played in helping activists fight against brutality and injustice.” In the same vein, Havens anchors a spirited, front-porch version of “Tombstone Blues” in Todd Haynes’ enigmatic 2007 investigation of the Dylan mystique, I’m Not There. In another testament to the timeless quality of Havens’ art Quentin Tarantino airs “Freedom” in his controversial 2012 release, Django Unchained.

Legacy of an Activist

Four decades later, in 2008, Havens’ last recording, Nobody Left to Crown, reveals a pervasive skepticism and deep unease, resonating as a lover’s ongoing quarrel with America. Selections such as “Fates,” “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” “Hurricane Waters,” “Lives in the Balance” and “Zeus’s Anger Roar” comprise an uncompromising indictment of life in an era of inconvenient truths and governmental gridlock.

For an artist so closely identified with an unrelenting ecological consciousness, it is ironic that this beloved troubadour passed away on Earth Day, April 22. On August 18 at the Bethel Woods Center for the Arts, a Day of Song and Remembrance will witness the scattering of Havens’ ashes at Max Yasgur’s farm. As an exemplar of evolved consciousness and a model for future generations, Havens represents a vital part of the American character: a conviction that the most radical idea in America is the long memory.

Kevin J. Aylmer currently teaches American and world history at Roxbury Community College and formerly served as the reggae, African and world music consultant to the original House of Blues in Cambridge, Mass.