On Feb. 11, 1990, South African political leader Nelson Mandela walked out of a prison after 27 years to fulfill his mission: dismantling the country’s apartheid regime. By 1994 the Nobel Prize winner had achieved just that by establishing the first democratic elections in South Africa and becoming its first black president. The towering statesman died last week at the age of 95.

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was born on July 18, 1918, in a tiny village in rural South Africa, known as Mvezo. “Rolihlahla” in the Xhosa language means “pulling the branch of a tree,” or more commonly refers to “troublemaker.” Mandela’s mother — Nosekeni Fanny — was the third of his father’s four wives.

His father was set to be chief, but a dispute with the local colonial magistrate changed the future that had been carved out. Mandela’s father lost his title and fortune, which forced the family to move to an even smaller village, Qunu.

The student

A family friend suggested to Mandela’s father that he have his young son baptized in the Methodist Church so that he could attend school. Mandela became the first in the family to receive a formal education, and as a reflection of the British bias within the educational system, he was given the first name “Nelson.”

When Mandela was 9, his father died of lung disease, and a high-ranking Tembu chief adopted Mandela. Chief Jongintaba Dalindyebo moved the young Mandela into his royal residence. Mandela took classes with the regent’s son and daughter in a one-room school next to the palace. He studied English, Xhosa, history and geography; he also learned the history of his country and people and how whites had arrived and taken the country from them.

Chief Jongintaba began grooming the teenage Mandela for high office, sending him to a Wesleyan — Methodist — mission school and Wesleyan College, which most Tembu royalty attended. Mandela succeeded there academically and also pursued track and boxing.

At 21, Mandela enrolled at the University College of Fort Hare, the only higher-learning center for blacks in South Africa. It was considered to be Africa’s Oxford or Harvard. He studied Roman Dutch law, which would have prepared him for a career in civil service as an interpreter or clerk — the best jobs available for black men. He also met Oliver Tambo there; the men would develop a lifelong bond.

During his second year, Mandela was elected to the Student Representative Council, or the SRC. But many students had been unhappy with how powerless the SRC was on campus, and a majority voted to boycott the elections. Mandela resigned from his post to join those students in their protest. School officials expelled him for insubordination.

Furious with Mandela, Chief Jongintaba told him to apologize so that he could return to school in the fall. The chief also announced that he had arranged a marriage for Mandela. Feeling trapped, Mandela ran away to Johannesburg, where he worked at odd jobs. He also finished his bachelor’s degree through correspondence courses at the University of South Africa.

In 1942, he enrolled at the University of Witwatersrand to study law and became active in the anti-apartheid movement and the African National Congress. For several decades, Mandela headed up a peaceful, nonviolent campaign against the South African government’s racist policies that included the 1952 Defiance Campaign and the1955 Congress of the People. He and Tambo also founded a law firm through which the pair offered free and low-cost legal advice to blacks.

The revolutionary

Mandela was arrested, along with 150 other dissidents, in 1956 and charged with treason; all were acquitted. During this time, a new generation of activists, known as the Africanists, was developing within the ANC and questioning the organization’s pacifist approach, which reflected the Mahatma Gandhi model of civil disobedience.

By 1959, the Africanists had broken away from the ANC to form the Pan-Africanist Congress. At a peaceful PAC-organized rally in the township of Sharpeville in 1960, in which thousands of people gathered to protest apartheid laws, police opened fire on the crowd, killing 69 people, including women and children. The South African government banned both the ANC and PAC in 1960, and both groups went into exile — and moved from passive to armed resistance.

Mandela made the move, too. In 1961 he co-founded Umkhonto we Sizwe, an armed offshoot of the ANC that focused on political sabotage and guerrilla tactics. He coordinated a three-day national workers’ strike that same year, for which he was arrested. The U.S. Central Intelligence Agency had tipped off the security police about Mandela’s whereabouts.

In October 1962, Mandela was sentenced to five years for coordinating the strike. But in 1963, during what became known as the Rivonia Trial, he and other ANC leaders found themselves facing life imprisonment. They were charged with guerrilla warfare and sabotage — the equivalent of treason — and for planning an invasion of South Africa. Mandela admitted only to sabotage. However, he, along with eight other defendants, received a life sentence.

The political prisoner

Mandela would spend 27 years in prison, 18 of them on Robben Island, off the Cape Town coast. While he received the harsh treatment as a black political prisoner, he was able to earn a bachelor’s degree in law through a University of London correspondence course. His mother and a son died in the late 1960s, but Mandela was not allowed to attend their funerals.

In a 1981 memoir, South African intelligence agent Gordon Winter unveiled a plot by the government to assassinate Mandela: The political prisoner would be allowed to escape and then shot during the recapture. The news of the foiled plan only made Mandela an even more potent symbol of black resistance, and an international outcry for his release began.

In the U.S., the Reagan administration maintained a policy of so-called constructive engagement regarding the apartheid government of South Africa, rejecting economic sanctions and divestment from the country, which the United Nations General Assembly demanded. Ronald Reagan, who considered the ANC a terrorist organization, said in 1981 that he was loyal to the apartheid regime because it was “a country that has stood by us in every war we’ve ever fought, a country that, strategically, is essential to the free world in its production of minerals.” (Long after his release — until 2008 — Mandela and other ANC members were not allowed to visit the U.S. outside of U.N. headquarters without a special waiver from the secretary of state because of their “terrorist” political affiliation.)

In 1982, he and the other ANC leaders were moved to Pollsmoor Prison, a maximum-security prison. President P.W. Botha granted Mandela’s release in 1985, but only if he renounced armed struggle. Mandela rejected the offer. Despite the groundswell of support for Mandela’s release, negotiations seemed to stall while Botha remained in office.

Botha suffered a stroke in 1989 and was replaced that year by Frederik Willem de Klerk. Mandela’s release finally took place in February 1990, and de Klerk also lifted the ban on the ANC, removed restrictions on political groups and suspended executions.

Mandela emerged from prison as committed and uncompromising as ever, urging other nations to continue their pressure on the South African government for constitutional reform. He also stated that the armed struggle would continue until blacks received the right to vote.

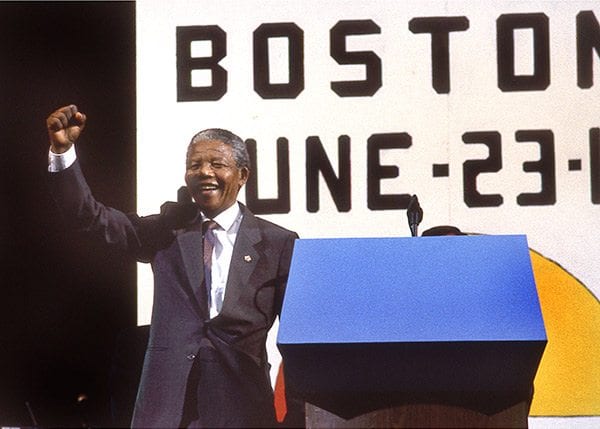

The triumphant president

In 1991, Mandela was elected president of the ANC, with his colleague Tambo serving as national chairperson. Mandela also engaged in often strained negotiations with de Klerk on developing the country’s first multiracial elections. Violence erupted — the 1993 assassination of ANC leader Chris Hani was just one example — and Mandela addressed the nation, urging calm.

In 1993, Mandela and de Klerk were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their work to dismantle apartheid. On April 27, 1994, South Africa held its first democratic elections. The following month, Mandela, at 75, was inaugurated as the country’s first black president. De Klerk was his first deputy.

Mandela released his autobiography, “Long Walk to Freedom,” in 1994. He had secretly written most of it while incarcerated. In 1995 the Queen of England presented him with the Order of Merit.

While in office, Mandela focused on transitioning the government from apartheid rule to a black majority. He utilized the country’s love of rugby to promote reconciliation between blacks and whites, even urging blacks to support the much loathed national rugby team. In 1995, the country hosted the World Cup. Mandela’s initiative was the subject of the film “Invictus,” starring Morgan Freeman as Mandela.

Mandela also worked to bolster the South African economy, which was near collapse. He established the Reconstruction and Development Plan, which funded initiatives to create jobs, fair housing and basic health care. In 1996 he signed into law a new South African Constitution, which guaranteed rights of minorities and freedom of expression as well as a solid centralized government.

The elder statesman

Mandela decided not to run for re-election in 1999 (ANC member Thabo Mbeki won election that year). Officially retired from politics, Mandela settled into his role as one of the world’s most revered elder statesmen, as well as an international civil rights icon. He actively raised funds for his foundation, which has built schools and clinics in South Africa’s rural areas. In his “retirement,” Mandela also went on to write several more books, including “No Easy Walk to Freedom,” “Nelson Mandela: The Struggle Is My Life” and “Nelson Mandela’s Favorite African Folktales.”

Mandela was committed to fighting AIDS, a disease that killed his son in 2005. He spoke at the International AIDS Conference in Durban in 2000 and in Bangkok in 2004. He also spoke out against the Mbeki government’s controversial response to the AIDS crisis (Mbeki questioned the link between HIV and the disease).

In 2001, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. In 2004, at age 85, Mandela retired from public life and returned to his native village of Qunu. He formed the Elders in 2007 to address global issues and promote peace. Members of the independent group of world leaders include Bishop Desmond Tutu, Kofi Annan, Ela Bhatt and Jimmy Carter.

Mandela’s 90th birthday in 2008 was the subject of international celebrations; one highlight was a concert in London’s Hyde Park. He also made a rare public appearance during the 2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa.

Among his numerous honors and awards, Mandela received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from George W. Bush in 2002. In 2004, the city of Johannesburg awarded him the highest honor: the Freedom of the City.

Mandela was married three times: to Evelyn Ntoko Mase, from 1944 to 1957, with whom he had two sons and two daughters; Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, from 1958 to1996, with whom he had two daughters; and Graça Machel, whom he married in 1998.

The Root