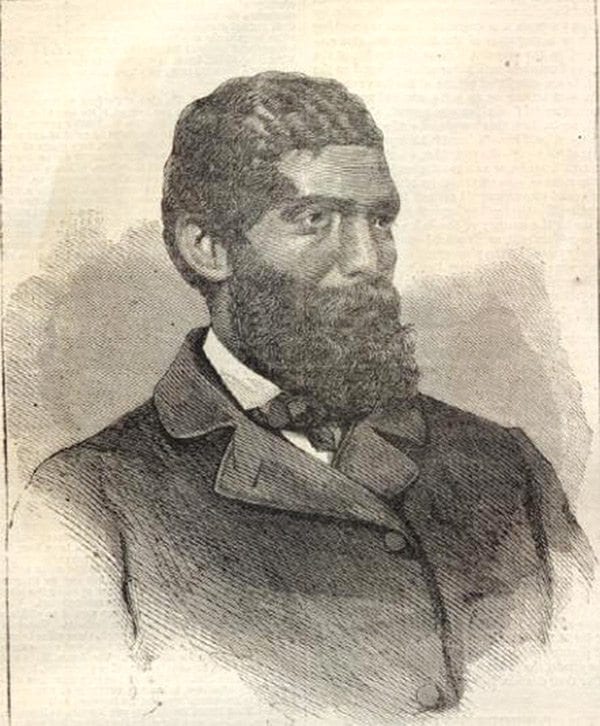

Dr. John S. Rock, a preeminent mid-19th century black abolitionist, dentist, doctor and lawyer, was one of Boston’s most eloquent and uncompromising champions of the rights of African Americans. He was born in Salem, N.J., on Oct. 13, 1825 to free parents Maria and John Rock. Educated in the public schools, Rock became a licensed schoolteacher in 1844. He taught in a one-room grammar school in his hometown for four years.

During that period, he studied medical textbooks and applied to several medical schools, but he was denied admittance because of his color. Thus, Rock turned to the field of dentistry, and after undertaking an apprenticeship with Samuel C. Harbert, a white dentist in Salem, he opened a dental practice in Philadelphia, Pa., in January 1850.

But Rock did not give up the hope of becoming a physician. He continued to apply to medical schools and, at last, gained admission to the American Medical College in Philadelphia. While attending that school, he practiced dentistry and taught classes at a night school for African Americans. In 1851, he received a silver medal for the creation of an improved variety of dentures.

Rock graduated from the American Medical College and married Philadelphia native Catherine Bowers in 1852. The couple moved to Boston the following year. They initially boarded at 66 Southac Street, the residence of abolitionist Lewis Hayden, where escaped slaves, targeted by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, found refuge. After Rock set up a practice in medicine and dentistry at 86 Cambridge Street, the Boston Vigilance Committee — an integrated abolitionist organization of which Hayden was a member — commissioned him to provide health care to ill fugitive slaves.

Rock was the second African American physician inducted into the Massachusetts Medical Society, the first being Dr. John V. DeGrasse, who was admitted in 1854. By that year, Rock and his wife had found a home at 60 Southac Street. She gave birth to three sons, Toussaint Lewis Hayden Rock, on April 13, 1854, John S. Rock Jr., in 1856, and Julian McCrea Rock, on Oct. 10, 1857.

Before moving to Boston, Rock had already been a prominent civil rights activist, fighting for black suffrage, and delivering lectures decrying the institution of American slavery, the American Colonization Society and the Fugitive Slave Act.

Like the abolitionist and orator Frederick Douglass, John Rock regarded the American Colonization Society as the slaveholder’s puppet and the black man’s enemy — an organization concerned solely with banishing free blacks. It supported neither the abolition of slavery nor the freeing and expatriation of the enslaved, and in Rock’s view, its scheme to remove free African Americans from their native country was no less wicked in principle than the African Slave Trade.

Rock was a gifted speaker. His lectures received favorable reviews. The Middlesex Journal, for example, wrote that they evinced “a fine education, superior scholarship, and much careful research.” The Philadelphia Christian Recorder found in Rock’s oratory “no bluster, no empty rant and beating of the air, no mere clamoring after effect,” and “no hollow words of empty sound.” The paper added, “His voice, smooth, pleasant, mellifluous, is exactly adapted to his calm and graceful action, and to his elegant diction.”

So it came as no surprise that he instantly became a sought-after public speaker in Boston. On more than one occasion, Rock was invited to speak on the anniversary of the death of Crispus Attucks, a black man, considered by many as the first martyr of the American Revolution.

He gave a speech at Faneuil Hall on March 5, 1858 at the Crispus Attucks Commemorative Festival, organized by abolitionist William Cooper Nell to protest the United States Supreme Court’s ruling in Dred Scott vs. Sandford (1857). Rock defended black men against malicious attacks on their reputation. Arguing that they were courageous, he cited the history of the bloody battles for freedom in Haiti, in which blacks “whipped the French” and gained their independence.

Rock embodied black pride and he loved his people. He told the gathering at Faneuil Hall, “I would have you understand, that not only do I love my race, but am pleased with my color, and while many colored persons may feel degraded by being called Negroes, and wish to be classed among other races more favored, I shall feel it my duty, my pleasure and my pride, to concentrate my feeble efforts in elevating to a fair position a race to which I am especially identified by feelings and by blood.” Displaying a black nationalistic sentiment, the doctor declared that “no man shall cause me to turn my back on my race. With it I will sink or swim.”

The prejudice that some whites had against Rock’s color gave him “no pain,” for he said, “If any man does not fancy my color, that is his business, and I shall not meddle with it. I shall give myself no trouble because he lacks good taste.”

Rock was a crusader for equal rights. At the annual meeting of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society on Jan. 27, 1860, he told the attendees, “I belong to that class of fanatics who believes that every man has the same inalienable rights; that any distinction found upon color is unjust; and that every man should be judged by his merits.” He was concerned about prejudice in the North, which robbed the black man of his inalienable rights, closed to him every avenue of wealth and position, and refused him even the common facilities for gaining an honest livelihood, thereby forcing him to remain poor and degraded, simply because of his color.

Less than six weeks after that speech, on March 5, 1860, at the 90th anniversary commemoration of death of Crispus Attucks, Rock again condemned Northern prejudice, believing that it deprived capable black men of employment opportunities. He said, “The free schools are open to our children, and from them have come forth young men who have finished their studies elsewhere, who speak two or three languages, and are capable of filling any post of profit and honor.” But there was “no field for these men,” he said, owing to “the embittered prejudices” of whites.

Rock may have delivered that lecture on the anniversary of the death of Attucks; however, having failed to see how black people actually benefited from his demise, he was not yet ready to idolize the martyr. The physician confessed to having a strong attachment to his native country and desiring to see it prosperous and happy, but as he saw it, America had not lived up to the promise of its revolution. Whites, he said, may have gained a little liberty, but to blacks American liberty was just “a name without meaning — a shadow without substance,” which retained “not even so much as the ghost of the original.”

Rock believed that the real American revolutionaries were Nat Turner, William Lloyd Garrison — the leading white abolitionist of the day — and John Brown. In his view, the only events in American history that even deserved commemoration at that time were Turner’s slave uprising of August 1831, the creation of the American Anti-Slavery Society and Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry.

Garrison co-founded the American Anti-Slavery Society at a convention in Philadelphia on Dec. 4, 1833. Rock described him as the “perfect embodiment of the moral insurrection of thought.” He said that he admired the abolitionist because, time and again, Garrison taught the American people that “unjust laws and compacts made by fathers are not binding upon their sons,” and that “the ‘higher law’ of God, which we are bound to execute, teaches us to do unto others as we would have them do unto us.”

No more than five months before that speech, John Brown had led an armed slave revolt in the town of Harpers Ferry, Va. If Garrison represented the pen, Rock considered Brown “the representative of that potent power, the sword,” which proposed “to settle at once the relation between master and slave” — peaceably if possible, “forcibly if it must.”

If blacks were going to be freed from the shackles of American slavery, violence, Rock forewarned, would be the only way. “It is a severe method; but to severe ills it is necessary to apply severe remedies,” he said. “Slavery has taken up the sword, and it is but just that it should perish by it.”

On the advice of his doctors, Rock gave up his medical practice in 1859 because of declining health. Undaunted, he decided to pursue a legal career. Through perseverance and diligent study, he became a member of the Suffolk Bar on Sept. 14, 1861, making him the fifth African American attorney to practice in the courts of Boston. That same year, Governor John A. Andrew appointed him Justice of the Peace for Boston and Suffolk County. Rock set up his law practice at 6 Tremont Street in Boston and advertised it in Garrison’s abolitionist paper, The Liberator.

In 1863, during the Civil War, the counselor helped assemble the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, a black unit in the Union Army. He would later lobby the government for equal pay for the members of the 54th and other black soldiers.

Rock’s wife, Catherine, died on Feb. 6, 1864 at the age of 32. About a year later, on February 1, 1865 — the day after Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution — with the help of United States Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, Rock was admitted to practice before the United States Supreme Court. At that time, it was led by Chief Justice Salmon Portland Chase, a recent appointment of President Abraham Lincoln.

A newspaper reported on February 4 that “the court came in as usual . . . and due proclamation was made that the country’s highest judicial tribunal was ready for the transaction of business. Senator Sumner immediately stepped forward, and presented a tall good looking colored gentleman to the court, saying, ‘I beg leave to present your Honors John S. Rock, Esq., a member of the bar of the Supreme Court of Massachusetts, and I ask that he be admitted to practice in this Court.’”

Chief Justice Chase bowed and replied, “He is admitted. Let him step forward and take the oath.” Upon taking that oath, Rock became the first black man to be admitted to the bar of that lofty tribunal. On that same day, through an arrangement with Congressman John Dennison Baldwin of Massachusetts, he became the first black to be received on the floor of the United States House of Representatives.

John S. Rock died of tuberculosis the following year, on Dec. 3.