William P. Jones’ ‘The March on Washington’ examines radical roots of march

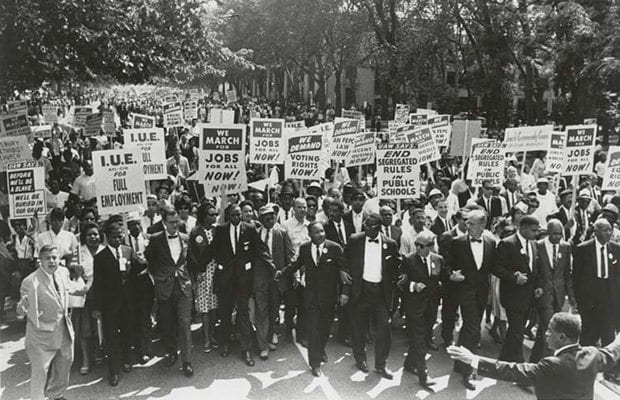

Protesters at the march carrying signs demanding new civil rights legislation.

As the nation gears up to mark the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington, a new book examines the lesser-known history of the landmark event.

William P. Jones: The March on Washington: Jobs, Freedom, and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights, offers a historical look into the making of the march from its radical roots in the 1940s to the organizational role of labor unions and women’s groups, and its ambitious economic agenda.

A history professor at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, Jones says that by shedding light on the past, the book will help readers see that the march was not just an icon of a bygone era, but also a “contemporary event” that is still relevant today.

“The march wasn’t a victory we can celebrate in the past,” Jones says, “but is part of an ongoing struggle that we can learn lessons from.”

The March on Washington focuses largely on the efforts of A. Phillip Randolph, the black trade unionist and leader of Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters, who first conceived of the march in 1941 as a call to end employment discrimination.

Randolph leveraged the march to persuade Franklin D. Roosevelt to issue an executive order prohibiting job discrimination by the armed forces and defense contractors — two of the nation’s biggest employers during World War II.

The possibility of tens of thousands of African Americans mobilizing in the nation’s capital frightened Roosevelt. As a result, less than a week before the march was scheduled to take place, the president issued the Fair Employment Act, an executive order similar to what Randolph had proposed. Roosevelt also created the Fair Employment Practices Committee to enforce these new policies.

While Roosevelt didn’t meet all of Randolph’s demands, it was enough to call off the march.

“We often see the goals of the Civil Rights Movement as starting with racial equality and expanding to include economic justice, but in fact, the reverse is the case,” Jones says. “They were initially concerned with economic justice and the issues about desegregation and voting rights in the South came later.”

After his first plan for a march never materialized, Randolph tried again — but failed — several times over the next two decades. It wasn’t until the 1960s, when Randolph — who had become head of the Negro American Labor Council — was battling segregation within labor unions and the exclusion of blacks from skilled jobs that the idea of a massive demonstration in Washington seemed possible again.

Using their tremendous organizing skills, Randolph and other march leaders secured pledges from the dozens of civil rights, labor and women’s groups across the country to mobilize their members.

“People think that Martin Luther King and others said, ‘Let’s have a march,’ sent out some press releases and people just showed up,” Jones says. “But institutions were central to getting people to the march.”

The date was set for Aug. 28, 1963, to coincide with the eighth anniversary of Emmett Till’s murder.

Like Randolph’s earlier vision, the march was aimed at pressuring John F. Kennedy and Congress into taking more aggressive steps to enforce civil rights. Some of the movement’s specific demands included a comprehensive civil rights law, access to decent and affordable housing, de-segregated education, the right to vote, raising the minimum wage and a federal program to train and place unemployed workers.

March organizers also wanted the federal government to withhold funding from programs that continued to discriminate against African Americans, and to reduce Congressional representation in states that refused to allow blacks to vote.

More than 200,000 people rallied in Washington, D.C., that day and heard speeches by Randolph, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Chairman John Lewis, National Urban League Director Whitney Young, NAACP leader Roy Wilkins and others.

While today, the march is defined by Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I have a dream” speech, Jones says that at the time, King’s words didn’t receive nearly as much attention.

In part, this was because “people didn’t see his speech as an expression of the goals of the movement” — King’s utopian vision starkly contrasted with the radicalism of the nine speakers before him. It was only after King’s death in 1968, Jones explains, that the speech became legend.

“He was assassinated at a time when many people were frustrated with the progress toward racial equality and some of the goals that had been issued at the ‘March on Washington,’” says Jones. “So his speech gained popularity in the 1970s and into the 1980s as an optimistic expression of a period when the Civil Rights Movement seemed to be gaining ground.”

The government didn’t meet all of the march organizers’ demands, but the achievements were profound. The most significant, Jones says, was building support for the Lyndon B. Johnson’s Civil Rights Act of 1964, a stronger version of a bill Kennedy had supported months before the mass mobilization.

But more broadly, Jones argues that the march successfully “shifted the conversation to push for rigorous federal policies aimed at creating racial equality and economic justice.” This not only inspired the Civil Rights Act, but also the Voting Rights Act and Johnson’s War on Poverty.

But today, just 50 years later, the Supreme Court is already reversing course — in particular, with its decision earlier this summer to strike down a key provision of the Voting Rights Act.

“What we saw this summer was an affirmation of the ideal of racial equality — that it’s a good thing to treat everyone equally,” says Jones, “but a decisive retreat from the idea that the federal government should play a hand or has the authority to uphold these ideals. The Supreme Court decision was a direct attack on the achievements of the march.”

This setback is just another reminder of the continued relevance of the march. Says Jones: “It was not something that we won, and now we can move on from. The issues that led people to participate in the march are very similar to what we’re still facing today.”