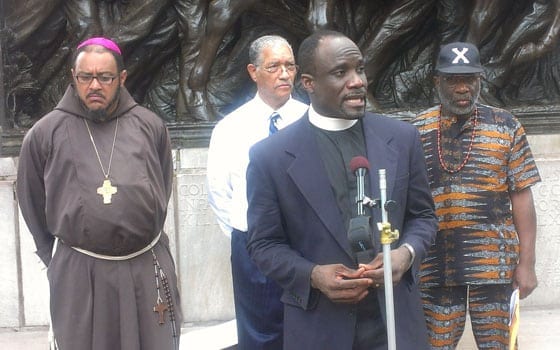

Black leaders held a press conference outside of the State House Wednesday morning opposing the “three strikes” legislation. Speakers include (L-R) Bishop Filipe C. Teixeira, Nation of Islam Minister Don Muhammad, Center for Church and Prison Director George Walters-Sleyon and Black Information Center Director Sadiki Kambon. (New Democracy photo)

A controversial measure known as the “three strikes” bill is several steps closer to becoming law. Last week, a conference committee approved a revised version of the bill, and soon afterwards, the State House of Representatives and the Senate overwhelmingly voted in favor of it.

Now, the bill sits on the desk of Gov. Deval Patrick, who has until Sunday to approve or veto the bill, or to send it back to the legislature with recommendations for changes.

The “three strikes” bill would impose mandatory sentences and reduce or eliminate the possibility of parole for repeat offenders. Supporters call it “Melissa’s bill,” a tribute to the 1999 murder victim Melissa Gosule, and claim it will keep violent offenders off the streets.

But critics contend the bill would funnel more people into an already crowded prison system, cost taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars, eliminate judicial discretion and harm communities of color.

“We’ve been opposed to this bill for a long time,” said Christopher Ott, communications director of the American Civil Liberties Union(ACLU) of Massachusetts. “We think it’s bad public policy that politicians are so concerned about looking tough on crime in an election year that they’re willing to sacrifice justice, public safety and economic savings.”

Liza Lunt, an attorney with the firm Zalkind, Rodriguez, Lunt and Duncan LLP, specializes in criminal defense and civil litigation. “The really short-sighted aspect to this is that no study has been done on the potential impact on the people of Massachusetts,” she said. “Not just the people being incarcerated, but also what it will cost.”

Housing one prisoner for one year costs the state about $50,000. Longer prison terms and reduced parole eligibility could cost over $100 million per year, according to Massachusetts Sentencing Commission data. And in the absence of any research, the effectiveness of this bill is also unknown.

As a report released by the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute at Harvard Law School explains, the bill is out of synch with the national trend to move away from three strikes laws. While 25 states passed habitual offender laws similar to Massachusetts’ between 1993 and 1996, only one has done so in the past decade. And of these initial 25, 16 are already rolling back some of the provisions to allow for more sentencing flexibility.

It is this inflexibility that troubles many of the bill’s critics. “They’ve taken out any judicial discretion,” said Lunt of the newest version of the bill. “There’s no ability for a judge to tailor a sentence to an individual.”

Traditionally, the judge determines the sentence based on all the facts and circumstances surrounding the crime — and the defendant.

Under the “three strikes bill,” however, mandatory sentencing would eliminate judicial discretion and all the power would shift to the prosecutor, who determines which crime — and by extension, which sentence — a defendant will be charged with.

“I think it will affect communities of color disproportionately, as these draconian measures always do,” Lunt continued.

As she explained, the bill would lead to higher rates of incarceration, not only in the application of the bill, but also because prosecutors may use it as a bargaining tool to get longer prison sentences in plea deals with defendants trying to avoid getting a strike.

“Defendants who are three strikes eligible,” she said, “…will agree to a much lengthier sentence than he or she otherwise would because of this threat of the three strikes sentence will be over the person’s head.”

Black and Latino communities are already overrepresented in the state’s prison population, and critics say the bill would only exacerbate this trend. A letter, written by the Massachusetts Black and Latino Legislative Caucus to fellow congressmen points out, that while blacks and Latinos make up just 12 percent of the Commonwealth’s population, they comprise 56 percent of the prison population.

“This bill is an unacceptable missed opportunity to fix this grossly disproportionate representation while we are otherwise amending our sentencing laws to increase incarceration,” the letter reads. “Unnecessary and ineffective jail sentences devastate communities: they preclude valuable job training and educational opportunities, fracture families, and perpetuate a cycle of violence and crime that has had serious consequences on communities of color.”

Rather than harsher punishments, many activists argue that the state should instead put its resources toward programs that will help reduce crime in the first place.

Calling the bill “highly problematic,” Rev. George Walters-Sleyon, executive director of the Center for Church and Prison, said, “Massachusetts should be emphasizing how do we make these guys viable citizens.”

Mass incarceration, he continued, is not just a fiscal or legislative issue, but also a community one that has resulted in the “continuous breakdown of the black family structure.”

Now that the fate of the bill rests in Gov. Patrick’s hands, opponents are reaching out directly to the governor to make their disapproval known. When asked what ordinary people can do to fight this bill’s passage, Lunt responded: “What people can do right now is email or call the governor’s office and tell the governor that they don’t want this bill.”