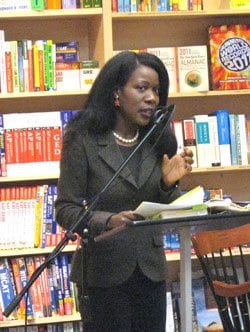

Author: Sandra LarsonPulitzer Prize-winning author Isabel Wilkerson discusses “The Warmth of Other Suns” at Porter Square Books on Jan. 31.

Between 1915 and 1970, some six million African American citizens left the South and its oppressive Jim Crow laws and became immigrants in their own country, seeking greater freedom in the cities of the Northeast, the Midwest and the West.

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Isabel Wilkerson chronicles this vast movement in her book, “The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration.” It has been an untold story, she says, locked up in the hearts and minds of the participants and often unknown to their children and grandchildren.

“One reason this story hasn’t been told in this way until now, is that the people didn’t talk about it,” she told an audience recently at Porter Square Books in Cambridge, one of many stops on a cross-country book tour she has been on since the book’s publication last September. “That was a generation that did not talk about the hardships they might have faced.”

Wilkerson, who is African American, said she learned the stories of her own parents’ migrations from Georgia and Virginia to Washington, D.C. only when she began reading her work to her mother.

“[But] these stories matter,” she said. “These individuals, multiplied by six million, made such a huge demographic sea change in this country.”

Wilkerson interviewed more than 1,200 people for the book, going to picnics and to churches, senior centers and American Association of Retired Persons meetings, she said, in what became a 15-year project.

She chose to tell the great migration story by focusing in detail on the lives of three individual migrants. Ida Mae Brandon Gladney rode the train with her husband and young children in 1937 from Chickasaw County, Miss. to Chicago; George Swanson Starling fled Eustis, Fla. for Harlem in 1945 after trying to organize orange pickers; and Robert Joseph Pershing Foster, a trained surgeon not allowed to work in southern hospitals, drove alone in 1953 from Monroe, La. to Los Angeles.

The three made their journeys in separate decades and followed different paths across the country, but they shared the yearning to leave and the strength to overcome obstacles in both the Old Country of cotton fields and orange groves and the New World of cities, apartments and factories.

It’s not hard to explain why blacks were willing and sometimes desperate to leave the South.

“Across the South,” Wilkerson writes, “someone was hanged or burned alive every four days from 1889 to 1929,” for such alleged crimes as “boastful remarks” or “trying to act like a white person.” Some lynchings were announced in advance in newspapers and drew crowds of thousands.

She tells of a black soldier who arrived back home in Georgia after serving in World War I. A group of white men harassed him, ordering him to take off his uniform and walk home from the train station in his underwear. He refused. Days later, a mob attacked him. He was beaten to death, wearing his uniform.

The book recounts some horrifying beatings and killings, but also brings to life the day-to-day, year-after-year insults Southern blacks endured.

Researching Jim Crow laws, Wilkerson said she found the system surprisingly extensive and sometimes ludicrously specific. In Birmingham, for instance, blacks and whites were forbidden to play checkers together.

“Someone actually sat down and wrote that into law,” she marveled.

But despite the dangers and humiliations, escape could be a bittersweet victory. Much was left behind.

Gone were the easy opportunities to “sit and chat over salt pork and grits with a beloved mother or a sister,” Wilkerson writes. In the cold North, migrants would miss the natural environment of the South, “screech owls and whippoorwills … paper-shell pecans, locust trees, dogwood trees, and chinaberries,” and the one-room churches with ancestors buried nearby.

In her research, the author got a close-up glimpse of how people in various “migration streams” carry on the traditions of their particular Southern regions.

The streams largely mirrored the train routes, though they were affected also by where factory scouts from various northern cities went to recruit labor during wartime when white workers became scarce.

Boston’s migration stream drew from the Carolinas, Virginia, Florida and Georgia; the same stream carried blacks to Washington, D.C. and to Harlem. Gladney was part of a second stream that led from the middle Southern states to Midwestern cities such as Chicago, Detroit and Milwaukee. The stream to Los Angeles, Oakland and Seattle mostly came from Texas and Louisiana.

“When I went to Mississippi and to Chicago, I found that there were food choices and accents and references that I did not understand. For example, they ate something called hog head cheese — I hadn’t heard of it. My Georgia-bred mother didn’t make it,” she said. In Texas, she was confronted with another unknown delicacy, oxtail.

“Food is a thing that indicates you’re from a certain background,” she said. “In my stream they ate shrimp and grits and scrapple. And turnip greens with sugar. I never knew other people didn’t put sugar on their greens.”

Doing research in New York, things felt more familiar, she said. “I was in my migration stream. And I’m in it here,” she added. “It’s no accident that I’m in Boston.” Wilkerson, who grew up in Washington, D.C., is a professor of journalism and director of the narrative non-fiction department at Boston University.

In the book, Wilkerson uses the immigration metaphor to show how these Southerners disembarking in northern cities were not unlike arrivals from Ireland and Italy and Poland and Lithuania, all struggling to forge new lives in a strange land. All told, she said, her three characters are inspiring examples of people taking charge of their lives in a way that was denied to them for so long.

Yet, of course, there were differences. The African Americans were immigrants in their own land. Once at their destinations, they had to live in specific delineated areas of town — and paid higher rents than the whites around them. Much-needed jobs often went to European immigrants instead of to American blacks.

“You’re carried all through the book with this reality that [the Southern blacks] were not unlike anyone who came across the Atlantic in steerage,” Wilkerson said in an interview after her talk. “What was driving them were the same desires that any immigrant has. But it makes the story all the more poignant and more tragic that they had to do that when they were citizens already.”