Historian Patricia Sullivan’s recent book on NAACP details hidden history of Civil Rights Movement

Ossian Sweet seemed to exemplify the black middle class dream. He completed his medical degree at Howard University, went on to establish his own practice in Detroit, later got married and with his wife, travelled to Austria and France to pursue advanced training in pediatrics and gynecology.

But when the successful doctor returned to Detroit and tried to purchase a new home, he was met with resistance. Seeing that they were black, realtors immediately turned the couple away from houses in white neighborhoods. When the Sweets eventually did purchase a home, far above the actual value of the house, white mobs arrived on their property to protest their presence.

One night, a mob numbering in the thousands converged on Sweet’s lawn and started shouting racial slurs and hurling rocks at the house. In response, Sweet’s younger brother fired a rifle from a window in the house, hitting one white man and killing another. The 10 black men in the Sweet’s home were then arrested and charged with murder.

The Sweet story typifies the racial animus of the early 1920s — housing discrimination, violence, unfair police treatment and disproportionate charges. Except in one way: despite the odds stacked against him, Sweet was found not guilty.

With the help of a new interracial civil rights organization, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Sweet raised enough money to hire one of the best lawyers in the country.

The Sweet case marked one of the NAACP’s first major legal victories and underscored the power the association would eventually wield.

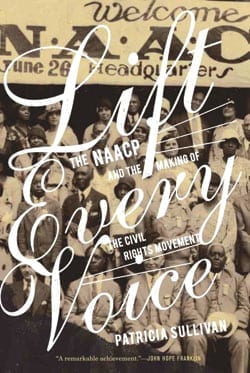

In an impressive new book, “Lift Every Voice: The NAACP and the Making of the Civil Rights Movement,” historian Patricia Sullivan chronicles the history of the NAACP, from its origins in 1909 to the landmark Brown v. Board decision in 1954. Relying on the well-preserved NAACP archives housed at the Library of Congress, Sullivan offers a fascinating view into the personalities, legal cases, struggles and victories of the country’s oldest civil rights organization.

“This book captures a hidden history,” Sullivan, a professor at the University of South Carolina and fellow at Harvard’s W.E.B. Du Bois Institute, said at the 2009 National Book Festival in Washington, D.C. just months after the publication of her work. “The public memory of the Civil Rights Movement pretty much begins with the Brown decision and the Montgomery Bus Boycott,” she explained. “But two generations prior to 1954 laid the groundwork that made the gains of the 1960s possible.”

The NAACP was conceived in 1909, when Oswald Garrison Villard, a white journalist, wrote “The Call,” a manifesto on race relations and an appeal to “believers in democracy to join in a national conference for the discussion of the present evils, the voicing of protests, and the renewal of the struggle for civil rights and political liberty.”

Several interracial meetings followed and were attended by prominent figures like W.E.B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, John Dewey, William Lloyd Garrison Jr. and Jane Addams. The name for the organization bears Du Bois’ influence — the use of “colored” instead of “negro” signaled a commitment to the advancement of all non-white people, not just blacks.

The formation of the NAACP was an unprecedented response to the ossification of the racial caste system in America. The 1896 Supreme Court ruling Plessy v. Ferguson established the “separate but equal” doctrine that legitimized racial segregation. Southern blacks were prevented from voting through a number of discriminatory practices, and terrorism reigned throughout the South — in the first 10 years of the 20th century, nearly 900 documented lynchings occurred.

From the outset, the NAACP focused on law and the courts as the grounds for racial reform, a reflection of “its interest in nationalizing the race question.” In 1913 the NAACP formed a legal bureau with the goal of assisting “any case where a colored person because of color is denied a right to which he is entitled,” in Du Bois’ words. Many lawyers worked on litigation in the national office, but civil rights giants Charles Hamilton Houston and Thurgood Marshall stood on the front line.

But the NAACP’s legal work was complemented by an equally important grassroots campaign. Du Bois established “The Crisis,” a monthly magazine that highlighted the NAACP’s activities and the injustices done to blacks across the nation. The association also sent field workers like Ella Baker throughout the country to conduct extensive research, raise funds, organize communities and mobilize black people around the NAACP’s core issues — voting rights, lynching, housing and education.

The synergy between the NAACP’s legal team at the national office and the association’s local branches led to numerous victories that began to erode the grip of Jim Crow. In 1918 and 1920, the NAACP was instrumental in introducing two anti-lynching bills to Congress. Both bills ultimately died, but the association succeeded in sparking “the first major congressional debate over federal protection of civil rights since the Reconstruction era.” More importantly, the association’s aggressive anti-lynching campaign seemed to influence public opinion — 20 years after the NAACP’s founding, lynching had declined considerably.

Many other victories followed. In 1924 the association challenged the Texas law that prohibited blacks from voting in the Democratic primary. The Supreme Court unanimously sided with the NAACP, ruling that the white-only primary was a violation of the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause. And in 1938, the NAACP brought the case of Lloyd Gaines, who was rejected from the University of Missouri Law School on racial grounds. Again the Supreme Court upheld the 14th Amendment, ruling that Gaines should be afforded the same education as whites.

Sullivan’s meticulously researched book is more than just a history of the NAACP — it is also a history of the black freedom struggle in the early 20th century. As she demonstrates throughout her work, the evolution of the association occurred in parallel with the evolution of black America. The Great Migration, blacks in the military, the crossover of black voters into the Democratic Party and the expanding racial segregation in the North all shaped African American life, and with it, the NAACP’s approach to securing racial equality.

But for Sullivan, the immense victories of the 1960s are not the end of her story. Many mechanisms of racism that were developed in the early 20th century are still present today, she reminded her audience at the 2009 National Book Festival. “We live with the consequences of that today,” she said. “We see [it] persisting in our schools, in housing patterns, in incarceration rates, so it’s a story that doesn’t have an end.

“But . . .” she continued, “this history is a hopeful one at its core.”