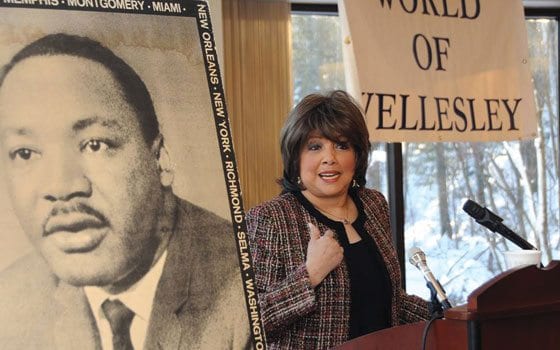

Award-winning TV journalist Carole Simpson recalls a meeting with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. that changed her life

For former ABC news anchor Carole Simpson, life has been a parade of firsts.

She became the first woman to broadcast radio news and the first African American woman to anchor television news in Chicago. She went on to become the first African American woman correspondent for a major network, and then rose to become the first African American woman news anchor for a major network.

Later, in 1992, Simpson became the first woman and the first minority to moderate a presidential debate.

But as expected, alongside her trailblazing success came considerable difficulty. In her new memoir, “NewsLady,” Simpson chronicles her battles with racism and sexism during her 40-year tenure as a journalist, showing that persistence always pays off.

Simpson grew up on the South Side of Chicago in the 1940s and ’50s, where she excelled in school and dreamed of becoming a journalist — an unheard of goal for a black girl at that time. Instead, her parents and teachers encouraged her to become a teacher, a more “reasonable” aspiration. But Simpson was stubborn, and eventually obtained a journalism degree from the University of Michigan.

After graduation, however, she found herself the only one in her class without a job. She was also the only person of color. So she turned to teaching at Tuskegee University in Alabama and then started working toward her master’s degree at the University of Iowa.

But the Watts riots of 1965 changed everything. After massive protests and violence broke out in the poor black neighborhood outside Los Angeles, news organizations all over the country suddenly wanted black reporters who could access the communities and ask the questions white reporters could not.

Simpson’s phone soon started ringing with job offers. “There were many black journalists who, like me, had been having trouble finding jobs,” Simpson writes. “But now our color had become an advantage, not a hindrance.” Accepting a reporting job at Chicago’s WCFL Radio in 1965, Simpson became the first woman to broadcast news in the city.

Although Simpson proved herself to be a talented reporter, sexism and racism continued to nag her. The news director of the station only assigned Simpson soft pieces, like childcare conferences, gala events, beauty pageants and baby animals — “women’s stories.”

Colleagues also attempted to sabotage her. During her first weeks on-air, Simpson said one man walked into the broadcast booth, “pulled down his pants and ‘mooned’ me while I was reading news about American deaths in Vietnam.”

Another time Simpson was reporting live on-scene when an anchorman knelt below her, reached up under her skirt and fondled her. “Did I shriek? Did I mess up? No, my delivery was smooth because I had learned not to be distracted by what was going on around me,” Simpson writes, recalling the incident. “Thanks to those shenanigans from my early radio days, I was able to finish any live report, whether I was in the midst of gunshots, surrounded by riot police beating black protestors, or walking in a minefield in Angola.”

Because of this and other incidents, Simpson says that sexism was a greater obstacle in her career than racism. “I more often heard, ‘you can’t do this because you’re a woman,’ rather than, ‘you can’t do this because you’re black,’ ” Simpson told the Banner in an interview.

But Simpson only used these obstacles to motivate herself. “I wasn’t going to let ‘No’s’ stop me,” she writes. “I would use them like vitamin pills to give me the strength to wage my struggle to reach my goals.”

And during her first year as a radio news reporter, Simpson received help from an unlikely source — Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. In 1966, Dr. King traveled to Chicago, but no one in the press knew why. Determined to get the story, Simpson tracked him down to his hotel and waited 12 hours for him to emerge from his room.

When Dr. King finally did come out, he approached her and told her, “I admire your perseverance,” and explained that he came to Chicago to challenge housing segregation. As he got into the elevator, he said, “Young lady, I expect great things from you.”

With that brief conversation, Simpson scooped all the other reporters. “That put my name on the map — I had become someone in the Chicago press corps because none of the national reporters, none of the best reporters in Chicago had gotten that, but I had,” she told the Banner. “So I feel like I owe my career to him, because he really made me somebody.”

From there, Simpson’s career quickly took off. She relocated to Washington, D.C. where she became a senior correspondent and weekend anchor for ABC News, and covered major stories like Nelson Mandela’s 1991 release from prison. Simpson was also selected to moderate the 1992 presidential debate between George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton and Ross Perot. She was the first woman and the first minority to do so.

While much progress has been made since Simpson started her career in the 1960s, the new challenge in journalism is what she calls the “sexualization of television news.”

Anchors are selected for their looks, not their knowledge, Simpson explained, and skirts are getting shorter, shirts are getting lower and everything is getting tighter.

“I think it’s partly due to the economics of the industry — losing audiences, losing viewers — so they’re desperate to do whatever they can to attract viewers,” Simpson continued. “One of the things that seems to be ‘in’ these days is having beautiful people who don’t know anything delivering the news.”

As a result, important questions are not being asked and important stories are not being covered. “The black unemployment rate being twice as high as the white unemployment rate — why is that? Has anybody looked into that?” Simpson asked. “Do you realize that there are 17 million children going to bed hungry every night in America? Nobody’s looking into these stories.” Simpson faults the business side of news today.

But journalism shouldn’t be subjected to a business model, she argues. Journalism is “codified in the first amendment,” she said. “It’s the only profession that’s constitutionally guaranteed, and we don’t have a free press if we have bosses who want people who are pretty rather than smart.”

After 40 years as a broadcast journalist, Simpson retired from ABC in 2006 and moved to Boston to “be with family and to watch my grandchildren grow up.” She now teaches journalism at Emerson College.

When asked what she likes about her new home, Simpson laughed and cited proximity to family. “But,” she said, “all people talk about in Boston are sports! . . . I just can’t get into it.”