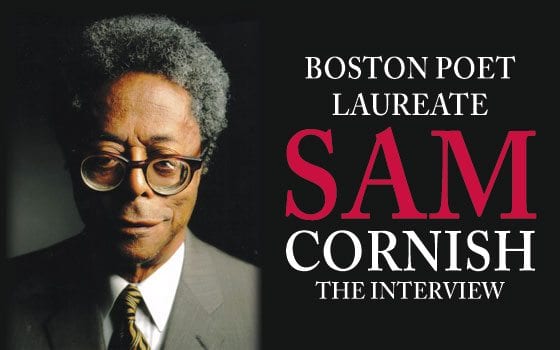

Poet talks history, politics and the Black Arts Movement

When I lived in the Brighton section of Boston in the 1980s I used to see poet Sam Cornish walking down Commonwealth Avenue.

With his thick glasses, powerful stride and intense stare, I thought to myself, ‘this cat means business.’ I never approached him, but I knew of his reputation as part of the “Boston Underground” school of poets, and knew he taught at Emerson College.

It wasn’t until he was appointed to the position of Boston Poet Laureate did I actually meet him, and now our paths have crossed more than a few times. Cornish was born in Baltimore, and for a long time commuted between his native city and Boston. He was a poor kid, raised by his mother and grandmother after his father died.

He was influenced by the small press movement in poetry, as well as the Black Arts Movement, but basically he has been viewed as a poet who is hard to classify. His poetry deals with slavery and civil rights, as well as pop culture: from Louie Armstrong to Frank Sinatra.

His poetry is usually stripped down and potent. Cornish’s breakthrough book of poetry was “Generations,” published in 1971.

The book is organized into five sections: Generations, Slaves, Family, Malcolm and others. He combined his own family with figures from African American history. Cornish received a National Endowment for the Arts Award in 1967 and 1969, he was the literature director at the Mass. Council of the Arts and owned a bookstore in Brookline for a number of years.

He has a number of poetry collections under his belt, the most recent: “An Apron Full of Beans” (CavanKerry). I talked with Cornish on my Somerville Cable Access TV Show: “Poet to Poet: Writer to Writer.”

Sam, you told me that you did not consider yourself to be part of the Black Arts Movement in the ’60s and ’70s. Yet I have read in a few places that people consider you an “unappreciated” figure of the movement. How would you define yourself?

What might distinguish me from poets of this generation in the movement, folks like: Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Giovanni, etc., was that I was influenced by a number of writers and sources that may not have been part of the influence and education in the Black Arts Movement.

Some of the poets in the movement came from a conventional Negro background. The Negro middle class: doctors, lawyers, teachers. I came from a poor family, raised by my mother and grandmother. My mother was forced to go on welfare when she could no longer work. I went to a neighborhood school and frequented the public library.

I bought books and as a result became interested in poetry. The poets that moved me were T.S. Eliot, Langston Hughes; prose writers like James T. Farrell and Richard Wright. As an adolescent I loved Farrell’s character Studs Lonigan. I could identify with him and I was motivated to find other books that I could identify with. I read books by George Simeon, the great French writer of psychological murder mysteries, for instance.

Who published many of the writers of the Black Arts Movement?

The Broadside Press. It was a small press that was based in Chicago. It was started by a man named Dudley Randall. They were publishing young black writers who were very militant and defined themselves as being “black” rather than “Negro.” There was a very strong political stance to them.

Didn’t you have a strong political slant to your work?

If I did it was politics that grew out of the 1930s. That was a mixture of left-leaning, the communist and the socialist.

This was in contrast to the militancy of the ’60s?

Yes. Because a lot of that was directed at whites generally. It was confrontational or abrasive. You were now BLACK and different from previous generations. You had no patience with your forefathers, your parents, those who were living as NEGROES. It was a very angry and self-destructive ideology. People like James Baldwin, Langston Hughes and Robert Hayden were viewed as not being pro-black.

Your poetry seems to be stripped down rather than weighted with ornate flourishes.

For me it is a choice of language. How do you describe something? How do you create a poem? How do you communicate? I would say that it is the influence of the hard world or the naturalistic writer, where you use the language that’s employed in common speech. At the same time you recognize the lyric possibilities in this language.

I have had my days when I had tons of words on the page. I realized though that it was necessary to use fewer words.

You told me that a poet should reveal something about himself in a poem?

I’m back and forth about that. There are poems where you can’t find the poet. There are novels where you can’t find the writer. I just feel very strongly that it is important to present yourself as honestly as you possibly can. Hold yourself up as a mirror people can see their selves [in] and vice a versa.

Poetry does provide an opportunity for people to hide themselves behind the language. They use the poem as a form of escape. And that’s OK as a form of entertainment.

You have talked about the photographer Walker Evans, who used to hide a camera under his coat, and snapped pictures of people that truly captured the moment, on the New York subway for instance. Should a poet be Walker Evans-like?

For me perhaps. But maybe not for others. I like the idea of interacting with people — different kinds of people.

So you must have been an admirer of the late Studs Terkel?

Very much so. He transcended the genre.

Your breakthrough poetry collection was “Generations,” published in 1971. How was it a breakthrough?

It might have been a breakthrough because the number of black writers being published at that time were few. The Beacon Press of Boston published it. As a black writer there may have been anger in the book. It was not an anger directed at White America. It attempted to describe living in an America that is black and white, and all the other things that go with it. The book is arranged like most of my books are: from past to present. It begins with a slave funeral and it ends with a sense of Apocalypse. The history comes from things I heard from home, and things I picked up from the neighborhoods, not to mention popular culture.

We have discussed Alfred Kazin’s memoir “A Walker in the City.” Kazin was inspired by pounding the pavement on the teeming streets of NYC. How about you in Boston?

I used to walk with a pocket camera, and took pictures as I walked. I would also walk with a notebook. I would describe things I would see, and imagined them as little scenarios. That was an important part of my day.

I get the impression that you are the consummate urban man. Could you survive in the country?

If I did live in the country I would like the freedom to move back and forth. I like to be near theatres, bookstores and cinemas.

You had your own small press: the Bean Bag Press. You hung with small press legends like Hugh Fox, and co- edited the anthology: “The Living Underground: An Anthology of Contemporary American Poetry” (Ghost Dance Press: 1969) with him. What is vital about the small press in the literary milieu?

Publication. The major presses publish very few books of poetry. They also have a fixed standard as to what they select. So you often get the same voices. The small press allows us to have a variety of voices. It allows us to be challenged, upset, disturbed and sometimes angered by what we read. The major press’ books are pleasant and fun to read. But they are not disturbing. They are basically not truthful. The small press has novelty, surprise, can be violent, and sometimes it can be damn good poetry.

What are your goals in your position of Boston Poet Laureate?

Right now I am available for people through the library and also through Mayor Menino’s office. If people call and request my presence at a school or senior citizen’s center, or where people would like a poet, I go. I try to be the person to bring a poem to people who might not read poetry, or those who want to talk to a poet about the craft.

Doug Holder is founder of the Ibbetson Street Press. This interview initially aired in 2008.