Anniversary focuses on pride, progress

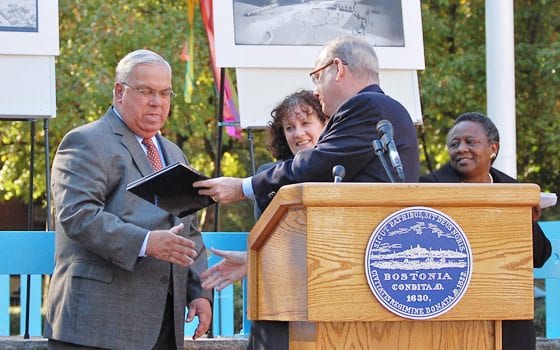

The Boston Housing Authority celebrated its 75th birthday this month and Mayor Thomas M. Menino (top left) was in attendance.

| The agency is honoring the milestone with an exhibit of photos called “Opening Doors: The Boston Housing Authority 1935-2010,” that are on display at the Mayor’s Gallery in Boston City Hall through Oct. 31, 2010. At top is Bromley-Heath Day Care Center in Jamaica Plain, followed by the Columbia Point Health Center in Dorchester in the 1970s. Hundreds gathered at a dedication ceremony for Charlestown public housing development June 20, 1941. Young girls who currently live at Faneuil Gardens in Brighton are pictured at the bottom. (Photos courtesy of BHA) |

The Boston Housing Authority (BHA) turned 75 this month, and the agency honored the milestone with a month-long exhibit of photographs at Boston City Hall and a celebration, complete with a ceremonial birthday cake-cutting, held at the city’s oldest public housing development.

The BHA came into being on Oct. 1, 1935, as construction commenced on the Old Harbor Village development in South Boston. The 1016-unit complex that opened in 1938 near Andrew Square has since been renamed Mary Ellen McCormack for the mother of John W. McCormack, a former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Under fall sunshine in the courtyard of Mary Ellen McCormack on Oct. 8, an enthusiastic audience of public housing residents, tenant leaders and BHA maintenance staff listened to speeches, watched Mayor Thomas M. Menino cut the cake and continued the party over hot lunch served in a nearby church.

“I honestly tell you, I see a revival in public housing. I see a lot of investment,” Menino told the crowd.

“Just look at these grounds,” he said, gesturing to the complex’s expansive courtyard, lush with well-tended grass and shade trees. “And not just here — there’s great work being done on all these developments. People care about what goes on in housing today.”

The BHA seems to be on an upward path, though its long history is checkered with controversy. In his 2000 book, “From the Puritans to the Projects,” MIT Urban Design and Planning Professor Lawrence Vale chronicles public housing in Boston from ambitious mid-century goals of creating public works projects, clearing slums and housing war veterans, to the BHA’s eventual slide into deep trouble, and finally the slow but steady recovery continuing today.

From the start, there were bitter protests by landowners whose properties were seized by eminent domain to clear land for new housing projects. Beginning in the 1960s, the agency was rocked by racial discrimination lawsuits, struggles with drugs and crime, deteriorating buildings and financial troubles.

Vale describes an entrenched system of patronage that kept minority tenants out of the best developments. A 1964 memo from the city’s Advisory Committee on Minority Housing to Mayor John Collins includes a table listing “some of the better projects,” containing zero or few nonwhites, and “other less attractive projects reserved for problem families and Negroes.”

The BHA’s low point came in 1980, when Judge Paul G. Garrity ordered the agency into receivership. Garrity cited “gross mismanagement” leading to “incalculable human suffering” in conditions woefully unsanitary and unsafe.

The changes that began at that time, under the leadership of Lewis “Harry” Spence, have led to what Vale calls “one of the most major turnarounds of a distressed public agency in the history of this country.”

And at the agency’s 75th birthday party, trouble took a back seat to good humor, fierce pride and optimism about the future. Residents cheered and clapped when speakers uttered the name “Old Harbor Village” and lauded the neighborly spirit and warmth of public housing communities. The mayor touted current improvement projects and plans to “green” the developments.

BHA Administrator Bill McGonagle and District 2 City Councilor Bill Linehan reminisced about their days growing up in South Boston public housing developments (Mary Ellen McCormack and West Broadway, respectively) and playing ball in the common spaces.

The audience was mostly white, and the only person of color at the podium was Willie Mae Bennett-Fripp, executive director of the Committee for Boston Public Housing (CBPH), an independent agency established by the court in 1981 to give tenants a voice in BHA decisions.

Bennett-Fripp spent her childhood in the Orchard Park (now Orchard Gardens) and Cathedral developments.

“It was a time when we had the Irish side, and the colored side,” she recalled of Orchard Park. Despite the segregation, however, Bennett-Fripp had only warm words about her public housing experience.

“It was a wonderful place,” she continued. “You could play Red Rover on a summer night, and without any exaggeration, you could have 400 children playing outside in the summertime.”

Echoing other speakers, Bennett-Fripp emphasized and praised the supportive community of public housing.

“When you are born into public housing, or when you move into it, you come into a family — a family of love and support,” said Bennett-Fripp, as a chorus of hearty agreement rose from the audience. “Just like Billy [McGonagle] was emotional just now when he expressed the love a neighbor felt to help his family in need, there are thousands of those stories to tell.”

McGonagle and Menino highlighted the redevelopment and repair work spurred by a recent influx of federal funding. The city has just broken ground on improvement projects at Cathedral in the South End, Amory Street and Bromley-Heath in Jamaica Plain, and Old Colony in South Boston. The $40 million outlay represents a portion of the $73 million in American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) funds the BHA received last year.

“I remember the days when our public housing projects were riddled with crime,” Menino told the crowd. “But now, we’re about to enter a new era of sustainability and success for the housing authority.”

The BHA’s near future seems rosy. But like everything else in public housing, its improvement plans are not without controversy.

The era of creating large high-rise style projects on cleared land is long gone, and improving a development today almost always lowers its density. Updating apartments and creating a more appealing neighborhood means making units bigger and buildings smaller.

“When we redevelop, it’s a balancing act between trying to bring back as many units as we can, and creating housing that fits with the twenty-first century,” said McGonagle in an interview.

But public housing advocates watch and fear this net loss of affordable units, as nearly 20,000 low-income people wait for public housing vacancies. On the other hand, some complain even about the improved projects. In the case of the current Old Colony work, despite the “de-densifying” of an unattractive development, South Boston neighborhood associations are taking issue with a six-story elderly housing building planned within the complex, arguing the height is inappropriate for the surrounding neighborhood.

A set of 33 photos on display at the Mayor’s Gallery in City Hall through Oct. 31 — and perhaps viewable online in the future — provides the barest sketch of the agency’s 75-year life. Older pictures document razing and construction projects, groundbreaking ceremonies and ribbon-cuttings. Some show the dilapidated houses the projects replaced. Juxtaposed with the black-and-white archival images are a number of recent photographs taken by Rachel Boillot, who also worked as an intern archiving the BHA’s photographs and organizing the exhibit along with Lydia Agro, BHA’s director of communications.

The goal for the exhibit was “no stereotypes, no sensationalism, just ordinary life,” said Agro.

Boillot’s large color images feature people: a woman and her daughter on a porch in East Boston’s Maverick development gaze with pride at the flowers they tend; residents of all ages enjoy annual Unity Day festivities in various neighborhoods. The new pictures reflect the multi-cultural faces of Boston’s public housing today, where a system of mostly-white and mostly-black developments has evolved into a majority-minority population in nearly every development, with Latinos the fast-growing group and at least 10 languages spoken, according to BHA charts.

Between its 64 brick-and-mortar developments and the vouchers it administers for Section 8, the federal program that subsidizes monthly rent in privately owned buildings, the BHA serves an estimated 52,000 low-income tenants today.

It takes a huge operation to manage all this. But Boillot’s arresting image of three little girls at Faneuil Gardens development zooms in on the humans behind the numbers — and the agency’s reason for being. With shy smiles, hands on hips, eyes straight at the camera, these girls look ready to take on the world, if only given the chance.