“Princess Noire” Chronicles Talent and Temperament of Nina Simone

“Princess Noire” Chronicles Talent and Temperament of Nina Simone

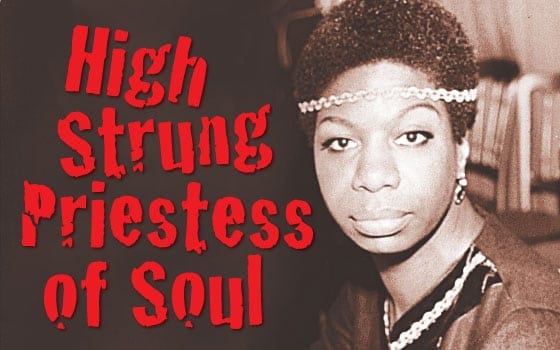

Just when one thinks the waters of aptitude are safe and talent is not commensurate with psychosis, along comes another biography affirming that artistic creativity comes with a cost. In “Princess Noire,” author Nadine Cohodas tells the story of singer-pianist Nina Simone, the celebrated performer nicknamed “The High Priestess of Soul.”

Born Eunice Waymon in Tryon, N.C. to a traveling minister mother and a father employed as a barber, trucker and small grocer, Eunice was sister to much older siblings and younger twins. Eunice displayed instrumental talent as a todddler. Her mother’s employer and another white townsperson paid for the little girl’s piano lessons with a British teacher named Mrs. Mazzanovich, who had moved from the Northeast.

“Miss Mazzy,” as Eunice came to call her, proved patient with the promising student, drilling her in Bach. Eunice aspired to a concert piano career. When she was 11, she gave a recital in Tryon’s whites-only library. When a white couple were given her parents seats and the Waymon’s were asked to sit further back, the child refused to play until the slight was rectified.

Miss Mazzy arranged for Eunice to receive a summer scholarship to Juilliard in 1950. There she studied for admission to the equally prestigious Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. She lived at West 145 and St. Nicholas Ave. in a bustling Harlem light years away from her southern hometown. She had trouble adjusting to the pace, marveled at the fancy clothing New York women wore and made few friends. Her summer curriculum consisted of a piano instruction course, repertoire and Fundamentals of Piano Practice.

Eunice did not pass her entrance audition to Curtis Institute and for a time, attributed it to racism. One teacher felt she possessed “great talent” but was “not a genius.” She moved to Philadelphia where she played local social benefits and took a job accompanying students at a vocal studio for a dollar an hour. Eunice spent a hefty $25 per lesson on private instruction from Vladmir Sokoloff, who was preparing her for another Curtis Institute audition.

She later moved to Atlantic City where she opened her own vocal studio, living above the rented space. The manager of Atlantic City’s Midtown Bar offered her a job and the first night of her engagement, Eunice did not sing. The manager ordered her to sing, or be fired. She knew classical and gospel music, and a few pop songs favored by her vocal students. When the manager asked how she wished to be billed, Eunice fused the elements of her given name into the more exotic “Nina Simone.”

In 1955, Frank Brookhouser, the “Man About Town” columnist for the “Philadelphia Evening Bulletin,” cited her “emotionally charged voice, individual style … reflects her classical training” and heard “sad memories” in her stylings. Nina also had a quirk — she waited for chatty patrons to quiet down before she played, even staring at offenders. Other club dates followed, as she outgrew the Curtis Institute’s audition cutoff age of 21.

In spring of 1957, agent Jerry Field signed Nina to the Queen Mary Room of Philly’s swank Rittenhouse Hotel, first for $100 a week, then $175. She signed her first recording contract with an indie label, Bethlehem Records. Though they recorded her with talented sidemen bassist Jimmy Bond and drummer “Tootie” Heath, she left the label and signed with Columbia Records, and at 27 years old, opened at Manhattan’s Village Vanguard backed by the Kenny Burrell Trio. She scored a chart hit with a song she disliked but mainstream audiences loved, the show-tune “I Love You Porgy.” Even as Nina headed to work the Playboy Jazz Festival in Chicago, she considered the money as a means to pay for a career as a classical pianist.

Nina’s peers thought she felt herself superior to her genre. She toured Africa with the American Society of African Culture in 1961 (actor Brock Peters, choreographer Geoffrey Holder and classical pianist Natalie Hinderas traveled with Simone). After her first North Carolina gig, her drummer was accused of stealing a white woman’s purse and stashing it in the restroom of the Raleigh train depot. Nina lashed out at the local police until the matter was dropped. She was rehearsing or composing in her den on Sept. 15, 1963, when she heard radio news of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church Sunday School bombing in Birmingham that took the lives of four young Negro girls.

“All truths that I had denied myself for so long rose up and slapped me in the face,” she later wrote, comparing the sentiment to St. Paul’s epiphany at Damascus. The entertainer thought of fashioning a weapon to hurt someone with. Her husband discouraged violence, telling her all she had was her music. Out of that hurt came her famed composition “Mississippi G—dam.”

In the mid-1960’s, Simone achieved a popularity and niche not reflected in record sales. She performed benefits for the Civil Rights Movement, and in an area the author dedicates far too little attention to, was one of the first nationally recognized Negro women to wear her hair naturally. Cohodas excels at painting vivid pictures of Simone in concert, her sullen glares at noisy fans, her trendy or cultural attire, and her moods.

In what would become another of her trends, Simone sued a former record label for $1 million dollars when they released old studio work without her approval. Her objection was as much based on the technical inferiority of the production as the absence of permission. As controversial as “Mississippi G—dam” was, two radio stations discontinued playing her “Four Women,” largely because the dramatic offering featured a stanza about a prostitute named “Sweet Thing” and a street tough named “Peaches.” White listeners were also uncomfortable with the lyrics mulatto character “Sephronia” sang, “My father was rich and white; He forced my mother late one night.”

Simone continued to connect better with live audiences than she did on wax. In London in ‘67, she slammed a piano lid and walked offstage. She shouted “Shut up” to West Indians in the London audience who vocally requested, “My Baby Cares For Me.” The author recounts a number of times she insulted white patrons, often declaring her performance was really for the black attendees. Simone’s anthem “Young, Gifted And Black” became late 1960’s hit and tour favorite, for a decade supplanting “Lift Ev’ry Voice” as an unofficial black national anthem. Simone was a seminal cultural figure of the Black-is-Beautiful era. Maya Angelou profiled her for “Redbook.” She posed for a fashion spread in 1971 for a new magazine for Black women called “Essence.”

Yet signs of emotional disturbance persisted. She berated Cincinnati fans for singing along too loudly to “Young, Gifted And Black.” She swore at weak microphones, fixed her glare or words on new sidemen’s missteps, and at the New Orleans Jazz Festival, moved B.B. King’s keyboard player offstage and brought pianist Don Pullen on during King’s set, telling the stunned musician “You’re a white boy” (and should not be playing with King). The fact that Nina often employed white sidemen mattered little. Neither did her repertoire. Though she covered the Bee Gee’s “To Love Somebody” and artists such as George Harrison and Janis Ian, she fussed at Eric Burdon of The Animals because they had covered her “House of The Rising Sun” to great success.

By the late 1970s the quality of her voice, never her strong suit, faded, and her keyboard playing became inconsistent. She bounced from home to home in Spain and France, finally settling in Carry-le-Rouet near Marseilles. Staff and siblings saw to it that she undergo medical observation. The author does not provide specifics as to Simone’s conditon, and while details may be subject to medical confidence, many biographers unearth their subject’s diagnosis. Cohodas does write Nina was prescribed schizophrenia medication.

Nina Simone’s final concert was in Poland in late June of 2002. She died in April 2003 at age 70 after an apparent second stroke. The Curtis Institute posthumously awarded her an honorary diploma for her “contributions to the art of music.” Simone was aware of the honor before she died. Princess Noire is a welcome addition to the shelf of music biography, and an entertaining look at a tortured soul.

Bijan C. Bayne is a cultural critic.

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Cagen-Luse_Men-at-store-e1713991226112-150x150.jpg)

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Cagen-Luse_Men-at-store-e1713991226112-848x569.jpg)