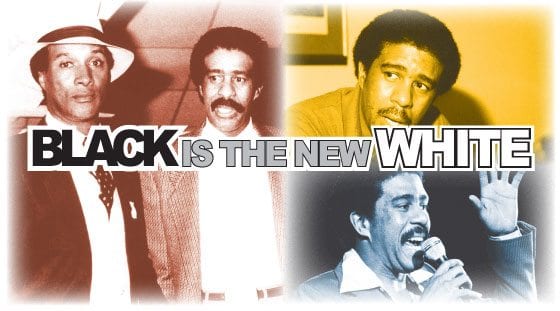

Mooney and Pryor refused to shuffle for Hollywood

Hollywood’s attitude toward black issues and performers has been the subject of criticism from the films of Robert Townsend (“Hollywood Shuffle”) and Spike Lee (“Bamboozled”), to the comedy and interviews of Dave Chappelle. Few inside observers have the laser-like analysis of veteran comedian and writer Paul Mooney, who takes us behind the cameras and into the boardrooms in his memoir “Black Is The New White.”

Mooney, 68, is a survivor of two worlds that consume lesser beings – standup comedy, and Hollywood. Raised in Shreveport, La. and Oakland, he recounts the dues he paid as a dancer on the Bay Area’s most popular teen music show, a fledgling actor, and woodshedding his standup material in nightclubs owned by Joan Rivers, Redd Foxx, and Pauly Shore’s mother Mitzi. Along the way, Mooney met up-and-coming comic Richard Pryor, a singular but emotionally troubled talent whose career was always a couple steps ahead of his friend’s.

The contemporaries bond at a late 1960s club called Candy Store, where Steve McQueen, Frank Sinatra, Mia Farrow, Ava Gardner, Flip Wilson and Billy Dee Williams hung out. Mooney and Pryor find common ground: both their grandfathers were hunters, they grew up in river cities (Pryor famously in a Peoria, Ill. brothel) and they both despised the Hollywood system and its limits on black freedom of speech.

One major difference is Pryor needs more love and affirmation, the classic inspiration for standup comedy, while Mooney received so much adoration in childhood, he is more “self-contained.” Pryor claimed he didn’t care less what the studio suits thought, Mooney doesn’t.

The strengths of this autobiography are Mooney’s insight about his gifted best friend, and his frankness about the entertainment industry. He feels Pryor was a junkie first and a comic genius second, but realizes the public would reverse the order. The author didn’t “hate (Pryor) because he’s a degenerate drug user,” nor “love him because he’s a comic genius. I love him because he’s Richard.”

Mooney’s resume is a psychedelic collage — he was a dancer on Hugh Hefner’s syndicated late 60’s series “Playboy After Dark,” meeting guests such as Linda Rondstadt, Sonny and Cher, Billy Eckstine, and Ike and Tina Turner. He sold shoes by day and honed his act free of charge at the Comedy Store when the spot was new. He toured with an anti-war comedy troupe called “FTA” (for F— The Army) run by Jane Fonda. The book is full of anecdotes about the famous before they were celebs, in some cases before they changed their names.

Mooney spares no details, no matter how scandalous or personal. He writes that Pryor’s transition from a clean cut, Bill Cosby style performer to an in-your-face comic who addressed race relations, was “midwifed by” Malcolm X and Marvin Gaye. Pryor holed up in his home reading the former, and listening to the latter’s 1971 album “What’s Going On.” Mooney introduces Pryor to his old high school buddy and former Black Panther leader Huey P. Newton. The Richard most of the world knows emerged from that period.

Yet America embraced the new, edgy Richard – his mid-1970’s albums won Grammys, his live concert films sold out theatres. In the background, Mooney wrote killer one-liners for the NBC hit “Sanford And Son,” created the famous 1975 “Saturday Night Live” skit in which Pryor and Chevy Chase traded racist epithets during a personnel interview, fighting producers and nervous censors all the way. The execs edited Mooney’s best bits, and producers distanced themselves from his “angry” humor. Routines about driving while black – or sitting U.S. presidents – were too hot even for the liberal 1970’s. To the author, race trumps financial profit in show biz.

Mooney and Pryor were the first mainstream comics to drop the “n-word” and employ the Oedipal expletive. Mooney and Pryor understood white audience members would laugh at the “n-word” out of nervousness and blacks out of recognition of street talk. This made the word territory on which white comics would not tread.

Though Pryor became king of his craft, Mooney says such status tortured Richard, who felt “mainstream popularity” was synonymous with “sellout.” The drinking and drugging are there – another part of Pryor’s life Mooney could not share. Hollywood’s invisible man, Mooney discovered and cast Sandra Bernhard, gave a young Robin Williams work on “The Richard Pryor Show” (before “Mork and Mindy”), and championed the careers of future sit-com stars Brad Garrett and Marsha Warfield at “The Comedy Store.”

It was Mooney who demanded that owner Mitzi Shore pay the comics, among them Jay Leno and David Letterman. “The Store” was Mooney’s longtime base of operations, as Goldie Hawn, Burt Reynolds and Sally Field, Donny Osmond and Lee and Farrah Fawcett Majors caught the shows. Mooney and Pryor had corroborative disappointments — Pryor was promised the starring role in “Blazing Saddles,” a script Pryor originally developed for himself as “Tex X.”

We hear the inside story of Pryor’s notorious demise — shooting up his wife’s car, setting himself on fire while free-basing cocaine, making a painful biopic and enduring multiple sclerosis. During these years, rising comics Eddie Murphy, Keenan Ivory Wayans and Dave Chappelle (who wrote the foreword to the book) borrow from and express their debt to Pryor and all hire Mooney as opening act (Murphy), writer (Wayans), or cast member (Chappelle).

It was Mooney who conceived the popular “In Living Color” character Homey Da Clown. You’ll never guess who taught then-Sen. Obama the fist bump. The author explains why he abandoned usage of the “n” word long after others made the same decision, including Pryor after a late 1970’s visit to Kenya. Poseurs, moguls and addicts are all presented as nakedly as Pryor in his controversial 1977 birthday suit sketch on his NBC show.

This is not a book of jokes; imagine sitting all night in a living room with an entertainment pro regaling you with, “True story, before anyone ever heard of so-and-so….”

“Black Is The New White” tells some agonizing truths about America and the industry that most occupies our fascination. Mooney has used his invisibility as a superpower for good.

Bijan C. Bayne is a Boston-born cultural critic.