Willie Mays was talented, but what made him one of the greatest was his baseball IQ

Baseball may no longer be considered America’s national pastime, but it has given the country more heroes (and villains) than the other major team sports combined.

It is a sport rife with anecdotes, legends and numerical trivia committed to memory. Observers differ as to who was or is the game’s greatest player, but none deny that the athlete who thrilled the most fans over the longest period was Willie Mays.

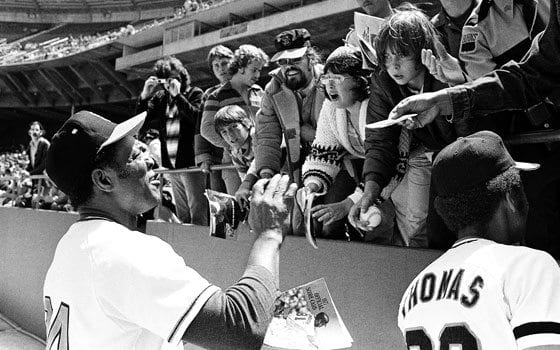

Millions of fans of all ethnicities claimed number 24 as their favorite player. Whether with his bat, glove, arm, mind or baserunning, Mays exhibited an excitement and intellect that often defied belief. In his authorized biography “Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend,” former New York Times and Wall Street Journal reporter James Hirsch (author of the bestseller “Hurricane: The Miraculous Journey of Rubin Carter”) has delivered a timely, measured study of a national idol.

Born near Birmingham, Ala. to a 19-year-old mill worker father nicknamed “Kittycat” (for his quickness on the ballfield) and 16-year-old high school basketball star named Annie Satterwhite, Mays was raised by his mother’s younger sisters Sarah and Ernestine.

The girl aunts were 13 and 9 years old when they took him in. Though his father contributed money and athletic encouragement when possible, Aunt Sarah became the most important figure in young Willie’s life. While Annie Satterwhite never married “Cat” Mays, she did marry another man and had a total of 10 children.

“Cat” Mays taught Willie to accentuate the positive, respond to Jim Crow with work rather than words, and avoid social vices. Because of his athletic talent, schoolteachers and extended family conspired to protect Mays, a disinterested student, from the chores and academic obligations that busied other boys.

As a teenager, Mays was a (colored) state championship quarterback in football, his county’s leading scorer in basketball, and the youngest baseball player on the TCI wire mill team, the semi-pro Chattanooga Choo Choos, and the Negro Leagues’ Birmingham Black Barons. On the mill squad, his 36-year-old father was a teammate.

In the fading Negro Leagues, Mays absorbed lessons on baseball strategy, accommodation to racism — and fashion. In 1950, three years after Jackie Robinson broke the major leagues’ color barrier, Mays signed with the New York Giants. He struggled early on as a hitter, but dazzled in the field, his throwing arm legendary, and no fair ball seemingly out of his reach.

Manager Leo Durocher emerged as a father figure, instilling confidence in his young centerfielder, and shielding him from the New York press. Mays arrived at an ideal place and time — the baseball Giants were rivals with Brooklyn’s Dodgers and the Bronx’s dynastic Yankees — and television was bringing live baseball into American homes.

Not everyone was excited. When Birmingham citizens gathered for a 1951 homecoming parade to hail the local celebrity, police Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor canceled the festivities rather than honor a colored native.

Mays became a leading cultural figure of 1950s America, his boyish enthusiasm contagious to teammates and unthreatening to sportswriters. He lived alone in Harlem, chaperoned and counseled by former Harlem Rens basketball star and New York Boxing Commissioner Frank Forbes. In an era when even star athletes were more accessible, he delighted neighboring boys by participating in their stickball games.

By all accounts, Willie Mays modernized baseball. He was the first big leaguer to combine the glamorous home run ability of Babe Ruth with the daring base-running of Ty Cobb. His success led National League teams to build their lineups around swift black and Latino stars. He made superhero catches, and Herculean throws.

Hirsch paints vivid details of some of Mays’ most memorable plays, unique not merely for their athleticism, but for their high baseball intelligence. Those who cite Mays as baseball’s ideal five-tool player (one who could hit, hit for power, run bases, field and throw), overlook a sixth and most important element that triggered those storybook feats — Mays’ anticipation and baseball sense.

No other outfielder briefed their pitchers on rival batting orders, or positioned teammates for batters. Mays ran bases not only with his own progress in mind, but to engage fielders while his teammates advanced. Such acumen set him apart from even Babe Ruth, Hank Aaron, and batting scientist Ted Williams.

Hirsch chronicles the racial slights his subject faced in segregated minor league towns and from managers and journalists. Of such incidents, Mays adopted his father’s attitude (and in Hirsch’s opinion, prevailing Southern convention) of “Just play hard.”

When Jackie Robinson publicly denounced him for his silence on race relations, Mays pointed to his involvement with boys’ homes and Job Corps, and in the individual lives of troubled youth such as a then-14-year-old juvenile offender named O.J. Simpson.

When a section of San Francisco erupted in riots in 1966, his public service announcements about a hastily planned Giants game telecast from Atlanta helped restore calm.

Hirsch reveals Mays’ feelings: disappointment when harangued or benched by a manager; disbelief when the Giants abandoned New York for San Francisco; and disdain when asked to make personal appearances or memorabilia without compensation.

His loyalty to teammates, owners and especially young fans engendered forgiveness others found incomprehensible. Mays met injury, bigotry and divorce without complaint. His character was never more evident than when he helped defuse a notorious 1965 brawl in which his teammate, pitcher Juan Marichal, clubbed attacking Dodger catcher John Roseboro with a bat. Mays tackled his teammates entering the fray. He calmed a bleeding Roseboro and escorted him to the Los Angeles bench, speaking words of reason while cradling his wounded head like a brother would.

Mays’ love of the game was transparent; he battled off-season fatigue to play winter ball in Puerto Rico and Japan, and led barnstorming tours featuring black major leaguers until 1962, long after such spectacle was routine.

Despite his on-the-field intelligence, Mays made poor off-the-field choices. He purchased homes and furnishings beyond his means. Friends believed his first wife, the twice-divorced Marguerite Chapman, was materialistic and aloof. His second wife, the former Mae Allen, is unanimously considered a godsend (whom Mays now cares for, as she has Alzheimer’s disease). Mays’ relationship with his adopted (first marriage) son Michael, while attentive when the boy was small, is not as intimate these days.

In retirement, Mays found work as a promotional greeter at a Las Vegas casino, a decision that earned him a six-year ban from major league baseball. He lent unfailing support to godson Barry Bonds when accusations of steroid usage swirled around the son of Mays’ former outfield protégé Bobby Bonds.

On May 6, 2010, the kid who loved Harlem stickball turns 79. If the figure sounds improbable, it is because numbers have never been sufficient to describe one of the greatest players of the last century.

Bijan C. Bayne is a frequent contributor to the Bay State Banner.