The Kennedy brothers and me: Seemingly so different, but brothers under the skin

The Kennedy brothers and me: Seemingly so different, but brothers under the skin

Outwardly, in 1960 there could hardly have been any greater distance between John, Robert and Edward Kennedy and me. Outwardly, we could hardly be having more disparate experiences.

They, with their whiteness and wealth and lives at the very top of America’s racially stratified society. Me, a black working-class boy of 12, growing up in one of Boston’s two black “red light” districts and seemingly facing a future that — by dint of poverty and race — was, at best, cloudy.

Yet within the decade, the transformation of American society that the Kennedy brothers were both a product of and helped further would find me traversing on my own some of their old college trails — living first in Jack’s freshman dormitory, then Jack and Teddy’s upper-class dormitory, and joining Jack and Bobby’s undergraduate club. I felt about my attendance there as they must have felt: that it was my destiny.

But long before then, I had felt the Kennedy brothers and I had two powerful things in common.

The first was Boston. Not just the Boston of the shiny American-war-of-independence myths, nor the Boston whose world-renowned colleges, universities and hospitals lent the city a glossy patina. Most of all, I felt we were connected via the other, grittier Boston: the working-class city of old-fashioned, deeply entrenched mores — and prejudices.

Although the Kennedy brothers and their sisters had in fact grown up everywhere but Boston — Hyannisport, Bronxville and Palm Beach, among other places — the Kennedy family was straight up from that Irish Catholic immigrant mass that began collecting in Boston before the Civil War.

In 1960, in the last months of JFK’s (barely) successful campaign for the presidency, I entered the seventh grade of the same public secondary school that Joseph P. Kennedy, the family’s patriarch, had navigated to great success nearly 60 years before. I’ve always believed one can’t underestimate the impact that campaign and victory had on an entire generation of Boston youth. I began to feel its impact on me almost immediately — beginning with a surge of pride in a school I wasn’t then sure I liked, because the school band was subsequently invited to march in JFK’s inaugural parade.

It would be more than two decades before I felt I had plumbed all the facets of my connection with those three Kennedy brothers. Two decades before I fully understood how important it had been in helping me, a Chicago-born black boy, come to a consider myself a Bostonian.

And a black Bostonian. The second reason I came to feel so close to the Kennedy boys was their involvement in the civil rights movement exploding across the nation — and in Boston, too, via the school desegregation struggle that led to the 1974 federal court school desegregation order.

To be sure, JFK’s involvement was at first as distant as he could make it. Personally, he barely knew any blacks, and the increasing intensity of civil rights activism during the first two years of his presidency exasperated him. It enormously complicated his trying to move his political agenda through a Congress in which the Southern segregationist bloc was still powerful.

Yet, to my adolescent eyes, JFK fused two concepts that were to become the foundation of the political consciousness I was then forging for myself. One was the idealism of the civil rights movement — that sense of the need for individuals to act heroically in pursuit of their rights as Americans, and to stand with those less fortunate and under siege. The second was the lofty, centuries-old Boston ideal that exalted public service over private-sector gain.

In that regard, how fortunate I, he and white America as a whole were to have in African Americans a people committed, despite three and a half centuries of brutal oppression, to the pursuit of their rights by any peaceful means necessary. Blacks’ choice of nonviolent reform over violence gave America, and, in that moment, JFK, time to better understand what democracy means. Systemically speaking, then, JFK was the perfect complement to his other brother-under-the-skin, Martin Luther King Jr.

Bobby’s transformation after JFK’s assassination and his heartfelt speech to an anguished, predominantly black throng in Indianapolis on the night King was murdered in April 1968 sealed his place in my pantheon of heroes — a decision that was to be underscored in the unbelievably tragic moment of his assassination little more than a month later.

It was left to Teddy, as it turned out, to both provide a moral center for, and lead the legislative nuts-and-bolts effort of, the ongoing campaign to retrieve America’s promise from the dustbin of its history. His extraordinarily substantive record in that regard speaks volumes about the work that was needed — and still is needed — to make America a more perfect union.

I can and do look at the Kennedy brothers in national, even cosmic terms. Their contributions to the betterment of humankind will stand the test of time. But I also remember them with what for me is a deep pride of place.

They were Boston boys, and they were my brothers.

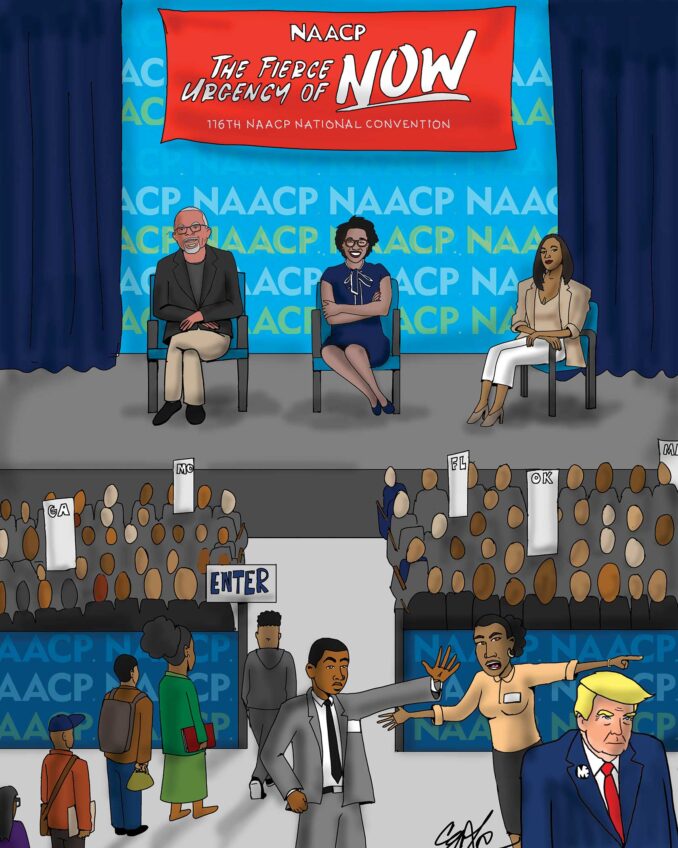

Lee A. Daniels is director of communications for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.