Theater group Company One’s latest play looks for the comedy in everyday tragedies

Theater group Company One’s latest play looks for the comedy in everyday tragedies

Think of “The Pain and the Itch” as emotional boot camp for the soul. Company One’s new production puts audiences through a rough-and-tumble workout in which no subject, from race to intimations of child abuse, is too difficult or risqué to tackle.

That may sound daunting to prospective audience members in search of entertainment. But Company One artistic director Shawn LaCount argues that the theatrical approach of “taking social issues and putting them under a microscope” is ultimately cathartic — and worthwhile.

“We’re framing parts of the human experience that really need questioning,” LaCount told the Banner in an interview last week. “How do we as a society, a city, a family or individual approach our relationships and social situations?”

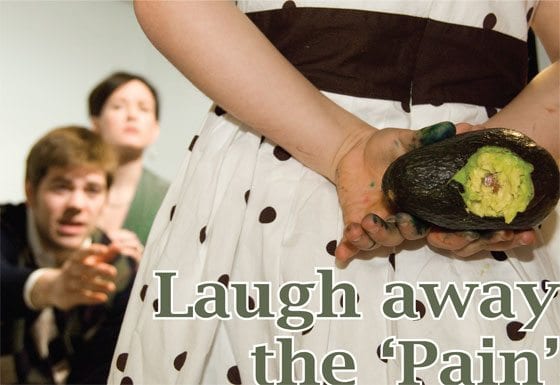

“The Pain and the Itch,” which debuts Friday at the BCA Plaza Theatre at the Boston Center for the Arts, is equal parts mystery and comedy, with a pinch of satire thrown in for good measure. The action revolves around the interactions of a white upper class family, LaCount explained.

“Throughout the play, they are retelling the story of their Thanksgiving dinner to a black man,” he said. That dinner is dominated by concern about the well-being of the family’s young daughter and the presence of a mysterious creature in the house that has been eating the family’s avocadoes.

“We’re not sure why the family is telling the man the story, and the play slowly unravels why he needs to know the information and how important and powerful he becomes in the eyes of the family,” LaCount said.

The play’s portrayal of a self-consciously well-educated family ranges from satiric to downright harsh. It exposes the delusions and inconsistencies of a married couple who are fastidious about their children’s physical safety — they carry their infant around in “a high-tech papoose” and try to keep the house free of potentially harmful chemicals — but remain oblivious to their children’s emotional needs, often forgetting that their preschool-age daughter is present when arguments turn into expletive-laden shouting matches.

Written by actor-turned-playwright Bruce Norris, the Boston production is directed by M. Bevin O’Gara, an artistic associate at the Huntington Theatre Company.

“I really think that Bruce has a cutting way of getting right to the heart of America today,” said O’Gara.

“Most people who would see this play can see something of themselves in it, but it’s not necessarily uncomfortable, because it’s a comedy and gives you the tension release to be able to laugh at yourself,” she added.

The casting process for the production presented a number of challenges, according to LaCount.

“One of the reasons why this play is so controversial is because it calls for a very young girl to be around this difficult family,” he said.

O’Gara explained that three girls between the ages of 7 and 8 alternate in their role as the lone child of the play, while a doll stands in for the married couple’s infant.

“There’s a lot of adults arguing in the play, so when we approached the auditions, we really needed girls who understand the difference between pretend and reality,” the director said. “We explained that to them from day one.”

In fact, O’Gara added, the three girls are sometimes more comfortable with the gap between reality and make-believe than some of the adult actors. While the adults have found it challenging to deliver their most anger-filled lines in the girls’ presence, the three children themselves, armed with precocious confidence, “are now at a point where they’re like, ‘Yeah, I know. It’s fake. It’s OK,’” O’Gara said.

Both LaCount and O’Gara pointed out that the play is set in a “Bush America,” but that its political and social relevance has endured, if not increased, in the early weeks of the Obama administration.

“Art transforms society and society transforms art,” said O’Gara. “When it was originally released, Bruce Norris wanted to write a play about fear in America and the way the family was viewed. Now, there’s a different context of taking responsibility and accepting the consequences of your own actions.”

The allegorical nature of the material now seems to allude to the country’s economic woes as it tackles the unknown, she added.

“The play is about trying to fix a massively bad situation by systematically shooting in the dark,” O’Gara said. “Attempts to rectify the situation dig us deeper into a hole.”

The economic downturn has a literal effect on the play as well, said artistic director LaCount, as Company One — like many other arts organizations — finds itself facing uncertain financial prospects.

“Everyone’s having a hard time. Every two weeks, I get an e-mail about a theater closing,” he said. “We have a relatively small budget and we recently had to cut $20,000 out of that budget. For us, that’s enormous.”

LaCount attributed the budget shortfall in part to cutbacks in foundation grants and awards, as well as the decline in audience numbers as consumers scale back on discretionary spending.

“We’ve had some rough times not making the audience count that we wanted,” he said. “Audiences are not so quick to come out at this point.”

Still, “the nice part about doing gutsy, fringy theater like we do is that you can only fall so far,” he said. “Our staff works mostly as volunteers and we do it because we love to do it and see it as a form of activism rather than business.

“My approach to the economy is that we’ll do whatever we have to do to continue to produce by cutting here or there and making sure we keep a presence in Boston,” he continued. “We try to bring people together who might not otherwise find themselves in the same room — different ages, different classes — to experience the American stories that we all understand, know and have our eyes on.”