American heritage on display at the DeCordova Museum

Just in time for the Fourth of July, a traveling vaudeville exhibition of our nation’s psyche rolled into the DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park in Lincoln.

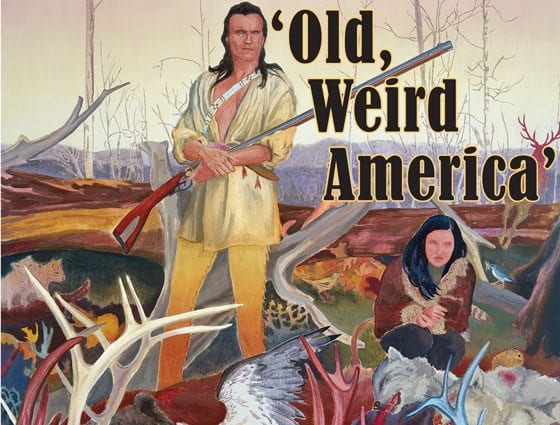

Fresh from its debut at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, whose senior curator, Toby Kamps, organized this exhibition, “The Old, Weird America: Folk Themes in Contemporary Art” presents contemporary works by 18 U.S. artists who are excavating fresh truths, old ghosts and abiding mysteries out of our nation’s heritage of memories and myths.

On view until Sept. 7, the exhibition borrows the title and theme (with permission) of a 1997 book by cultural critic Greil Marcus, “The Old, Weird America: The World of Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes,” which explores how Dylan rooted his music in old blues and folk songs.

More a panorama than a melting pot, the show presents artists with a mix of perspectives, including urban, gay, western, black, Hispanic, Native American and Appalachian. Whatever their preoccupations, they share an interest in what is missing or lost in our national narrative and reviving a past that is not even past — including the unfinished business of the Civil War. Many of the artists employ an art-making process that evokes America’s past in its attention to handiwork and traditional materials.

A cluster of installations turns the museum’s cavernous main gallery into a kind of carnival midway.

Allison Smith displays a row of life-sized dolls dressed as Civil War soldiers. Smith’s seven handmade figures, which resemble her, wear costumes she constructs out of 19th-century materials, including ceramic, linen, cotton and wool. Openly lesbian, Smith finds in the costumes of other eras a way to explore issues of identity and the experience of living outside the mainstream.

Sam Durant’s “Pilgrims and Indians, Planting and Reaping, Learning and Teaching” (2006) restages two dioramas that he purchased from the defunct Plymouth National Wax Museum. Mounted on a rotating platform, they literally tell two sides of the story.

One shows the traditional, feel-good scene described in the title. As the platform turns, another diorama depicts Captain Myles Standish slaying a Pequot Indian, an event that precipitated a bloody battle and its victory party — the Jamestown Colony’s first Thanksgiving in 1621.

A sprawling stage set of an installation by Margaret Kilgallen (1967-2001), “Main Drag” (2001) portrays a seedy neighborhood populated by panhandlers, surfer girls and woman-owned businesses — a car wash, bake shop and Internet café. Combining the bold graphics of hand-lettered signs and cartoon images of female figures, her funky structure celebrates the do-it-yourself ingenuity of its scrappy occupants.

Cynthia Norton’s enigmatic “Dancing Squared” (2004) is a kinetic sculpture that suspends four identical square-dance dresses from a four-armed frame. Each is a crinoline-lined, eyelet-trimmed confection of red-and-white square patchwork. Every five minutes, the dresses spring to life, whirring in a circle while the disco ball crowning the frame scatters spots of light on the walls. As they spin, the dancing dresses evoke the mystical, ecstatic precision of whirling dervishes or Shakers.

Works on paper appear alongside the installations. Brad Kahlhamer packs his ebullient ink-and-watercolor images with motifs that evoke his dual heritage as a Native American raised by German American adoptive parents in Wisconsin. In one, a snake-like totem pole slithers among assorted doodles and cartoons as well as skillfully sketched female friends, teepees, bison, skeletons and scruffy-looking eagles on the hunt.

In other galleries, paintings recast historic scenes with 21st-century techniques that heighten their violence.

Aaron Morse portrays James Fenimore Cooper’s buckskin-garbed hero, Hawkeye, as Daniel Day Lewis played him in the 1992 movie version of “The Last of the Mohicans.” In his painting, “The Good Hunt” (2006), the figure of Hawkeye stands before a denuded wilderness, surveying a pile of slaughtered wildlife. His eyes are gray slits without eyeballs, like those of an android action figure. Glass beads sparkle on the orange tongue of a slain bear, the bloody fangs of a fox, the glazed eye of a great-horned sheep and a live lizard’s silvery body.

Mixing pigments with urethane, Barnaby Furnas uses a high-octane palette to render explosive moments in American history with videogame spark. In “Assassination (Abraham Lincoln)” (2007), the blast of the assassin’s gunshot surrounds the president with a halo. “John Brown” (2005) imagines the resurrection of the militant abolitionist, who hovers above a battery of flaming rifles that resembles a field of flowers.

Dario Robleto’s “The Pause Became Permanence” (2005-2006) is a shrine to the three last surviving Civil War widows, one the wife of a Confederate soldier, and two whose husbands fought on the Union side. A cabinet displays their obituaries in black frames adorned with handmade paper flowers containing pulp from soldiers’ letters, and lockets of hair made from audiotapes of the last known recordings of Civil War soldiers.

Reading like a recipe to accompany incantations, Robleto’s list of materials includes ground hipbone dust, glass from the melted sand of the first atomic test, fragments of 45-rpm dance-craze records, and shell casings and medals from various wars. Like an alchemist, he transmutes evocative materials into relics that embody what has been lost, stirring a kind of empathy across time.

A virulent past that remains present — America’s complex and still-toxic legacy of slavery and racism — is the subject that African American artist Kara Walker has been exploring throughout her career. The recipient of a prestigious MacArthur Foundation “Genius” grant in 1997 at age 27, Walker is known for fearless and startling works that disturb just about everyone and excuse no one.

On view here is Walker’s searing 15-minute video, “8 Possible Beginnings or: The Creation of African-America, a Moving Picture by Kara E. Walker” (2005). Using the genteel tools of Victorian era cut-paper silhouettes and Balinese-style shadow-puppetry, Walker creates a savagely satirical epic creation myth. Mimicking a silent movie, the black and white film uses subtitles to tell its tale, which unfolds to excerpts from the soundtrack of the 1946 Disney film, “Song of the South.”

Restive captives on a slave ship are tossed overboard. They float to “The Motherland,” an island that morphs into a giant black female figure. She swallows and then defecates them onto a plantation in “The New World,” the antebellum South, where a muscular black male slave jigs with a skinny white male master who impregnates him. Other episodes include a scene in which Br’er Fox and Br’er Rabbit lynch three slaves.

This exhibition gathers artists whose weird tales illuminate our shared terrain, a landscape that is both battlefield and hallowed ground. Visit, and pack a picnic to savor the landscape outside the museum, a forested glade of sculptures alongside a sparkling pond.

“The Old, Weird America: Folk Themes in Contemporary Art” is on view through Sept. 7, 2009, at the DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park, 51 Sandy Pond Road, Lincoln. The museum is open Tuesday through Sunday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., and on select holidays. Admission is $12 for adults, $8 for seniors, college students and youth ages 6 to 18, and free for children 5 and under.

For more information, call 781-259-8355 or visit http://www.decordova.org.