Status quo strong at Sundance, but the tide’s turning

PARK CITY, Utah — It’s the place where independent film meets Hollywood glamour. High on this mountain town’s exclusive slopes, the 25-year-old Sundance Film Festival is supposed to showcase what’s on the cutting edge of the silver screen, inviting up-and-coming artists to become part of the very media landscape that shapes and dictates pop culture.

Ironically, though, the whole scene — the screenings, the parties, the panels, everything — is populated predominantly by a homogenous group of established filmmakers and business folk who already dictate that discussion. The hot spots where people rub shoulders are as overwhelmingly white as the snow-capped mountains that surround downtown.

What is so delicious about this irony is that the tide is turning, in both the content on display and the business model for shopping it.

One of the festival’s most watched and discussed films was “Push: Based on the Novel by Sapphire,” which tells the story of a troubled black high school teen fighting for her survival in 1980s Harlem. At home, she is locked in the physical and verbally abusive clutches of her mother. Outside her apartment, she is trying to earn her education while adapting to life as a teen mother, after being impregnated by her father twice.

The tale is startlingly honest and brutal. Director Lee Daniels said he knows that those who haven’t been exposed to such difficult circumstances could find the raw material unsettling.

“I did it because it was an expression of our frustration as black people,” he said.

During a packed press conference, Daniels voiced his skepticism about whether the film would be as well received in the Midwest as it had been in New York City, where it was shot. While that remains to be seen, the film did astoundingly well in Park City, winning Sundance’s Grand Jury Prize, the festival’s top dramatic film award, as well as the Audience Award. Actress Mo’Nique, who played the abusive mother in the film, also received top honors for her performance.

Daniels called the reception encouraging, saying that his goal for “Push” — which includes the subtitle about its source material to differentiate it from a science fiction film also called “Push” slated for release next month — was to demonstrate that while not all experiences are shared, pain and joy can be.

“It’s not about being black or white, it’s about self-identification,” Daniels said.

Other films dealing with race created quite a bit of buzz as well, including “Prom Night in Mississippi,” a documentary chronicling the life of high school students in Charleston, Miss., as they prepare for their prom. The event was significant, largely because it was the school’s first integrated prom — and it was held in 2008.

“My hope and 90 percent of my motivation was for young people to reflect on their attitudes and prejudices,” said Paul Saltzman, the documentary’s executive producer and director, who rode the film’s buzz to an appearance on CNN the day after its screening.

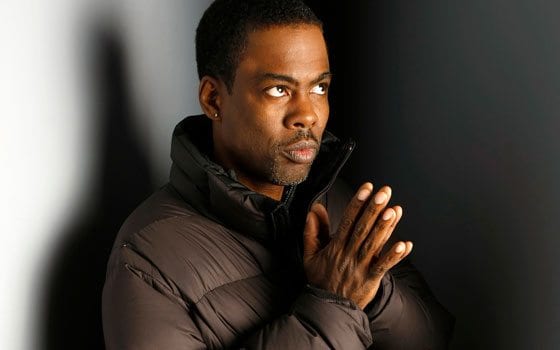

Another film earning a Sundance award was the HBO documentary “Good Hair,” which received a Special Jury Prize for U.S. Documentary for its portrayal of Chris Rock traveling around the world to explore the cultural significance of hairstyles.

The reaction to these films was encouraging, and pointed to an odd cultural dichotomy within the festival.

There were dozens of parties about town during Sundance, but one soiree featured a long line snaking beyond the velvet rope. The Def Jam/Island Records party was considered one of the hottest tickets in town, with hop-hop blaring from the doors and a predominantly white clientele outside, waiting eagerly to enter.

Other tents required passes, and at times, being a person of color meant having to show your press badge multiple times. At one particular party to which the press was specifically invited, a bouncer declined to let anyone else in, whether or not they had the badge. Another event to which members of the press were explicitly invited, the Ray-Ban/Creative Coalition Visionary Award presentation, featured an especially smug bouncer who flat-out denied official Sundance credentials.

While other Sundance volunteers were accommodating and helpful, the behavior of a few represented the elitism and exclusivity of Hollywood, a particularly intriguing dynamic, given the festival’s juxtaposition with the evolving political climate on display in Washington, D.C.

Panels and screenings were put on hold the day of President Barack Obama’s inauguration, and there seemed to be an excitement about change in the Park City air. But at the same time, there was fear of what that change might mean for an industry that has always been a closed society, one usually reigned by nepotism and favoritism.

Change was a key topic during one of the most highly attended panels of the festival’s opening. The panel, titled “Distribution Using Social Media Technologies,” discussed the ways in which studios are scrambling to make a profit while distributing a film on the cheap.

One filmmaker told the tale of having spent $700,000 making his feature film, only to be informed by a distributor that they would pay him just $50,000 for it. Not only that, the director said — the distributor told him he would lose any rights to creative control of how the film was marketed.

Unhappy with the offer, the filmmaker began looking for alternative ways to create buzz for his film, including generating an audience through the Web. That method of distribution was a popular subject at Slamdance, the alternative film festival located just a couple blocks up from the Sundance tents.

“Slamdance has been known for showcasing new talent,” said Peter Baxter, who co-founded the festival 15 years ago.

Baxter, an independent filmmaker himself, created the festival out of his own frustration.

“Basically it came from being rejected by Sundance,” he said. “We decided we would come together as a film community. We believed we were worthy of screening.”

Baxter’s frustration was exacerbated by the fact that even though Sundance touted itself as an open forum for new talent, many of the films being shown already had a lot of Hollywood support behind them.

“We were beginning to see films made that already had alliances with distributors [and] studios,” Baxter said.

Few of the films at Slamdance have any star power behind them, according to Baxter. While he does want the films showcased there to be picked up for distribution, he said he wants it to be a place where filmmakers and the audience have a say about what gets presented to the mainstream.

One of the avenues Baxter has worked on for helping Slamdance presenters accomplish that goal is Indieroad.net, an online model that will allow filmmakers to show their work online during the festival. If business players can’t get to the festival but want to stay in touch with new films being shown at Slamdance, Baxter said, IndieRoad.net provides an option.

“The online model, in the long run, I think it will succeed,” Baxter said.

Baxter noted that such new delivery methods may take some getting used to, but he said he believes the changing industry is taking power away from those who have held onto it for so long. So while there may be a chill in the hills of Park City, there are those who are warming up to what they see as an opportunity for change and empowerment.

“I believe the audience will become the gatekeepers [of] how popular a film will be,” Baxter said. “It’s a very exciting time.”