Towering obstacles in prosecuting the Oscar Grant killing

There’s a good chance that former Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) police officer Johannes Mehserle will be charged in the videotaped New Year’s Day killing of Oscar Grant, a young African American, in Oakland. But getting a conviction in the fatal shooting will be a far different matter.

On the surface, the case seems to be about as close to a slam dunk for a successful prosecution as any suit involving apparent police misconduct could be. There are at least two compelling videos that appear to show an unarmed and handcuffed Grant face down on the BART platform. Grant does not appear to be resisting the officers. Witnesses testified that Grant posed no threat to the officers. BART officials have offered the weak explanation that Mehserle might have mistakenly thought that he was reaching for his Taser gun. But expectations, witness testimony, videos and an implausible explanation by BART for the deadly shooting may not be enough to nail Mehserle.

The first obstacle to convicting cops charged with deadly force is the use of videos. Defense attorneys who represent cops charged in questionable fatal shootings have honed the discrediting of videotaped evidence to a fine art.

In a number of highly charged cases in cities across the country where the videos of police abuse have been widely televised to shocked millions, skilled defense attorneys have still won acquittals. They tell jurors that the videos are grainy and fuzzy, that the sound and recording quality are poor, that the tapes have missing pieces, and they omit events that show what provoked the officer to use force. They pound home the notion that such videos can be interpreted in many different ways. Their spin to jurors is that videos give a distorted, clouded and therefore invalid picture of why an officer may have used deadly force.

Defense attorneys don’t stop there. They also question the honesty, motives and background of the videographers. In the Grant killing, the two videos that were widely shown were shot by two young persons with cell phone cameras, one of whom refused to give his name.

In the rare occasions that a prosecutor brings charges against an officer for overuse of deadly force, the officers’ defense attorneys are top-notch and have had much experience defending police officers accused of misconduct. Police unions pay them and they spare no expense in their defense. The cops almost never serve any pre-trial jail time, and are promptly released on ridiculously low bail.

The next obstacle is the investigation. Police officials and prosecutors move at a deliberate, even glacial pace in compiling evidence, witness testimony and officer statements. The time delay works to the officer’s advantage, ensuring that their version of why officers used force is in total sync with the version given by other officers present. Mehserle’s quick resignation after the Grant shooting further blurs things — by leaving the department, he evaded an internal investigation and giving possible damning statements.

Then there’s the jury. Police defense attorneys seek to get as many middle-class whites on the panel as possible; the presumption is that such jurors are much more likely to believe the testimony of police and prosecution witnesses than black or young witnesses, defendants or even the victims. That’s no small point. In the great majority of deadly force killings, the victims are young African Americans, as Grant was, or Latinos, and the witnesses generally are young people and/or minorities, as was the case in the Grant killing.

Prosecutors have a daunting job trying to overcome pro-police attitudes and the negative racial stereotypes. Two Penn State University studies on racial perceptions and stereotypes, one in 2003 and a follow-up study in 2008, found that many whites are likely to associate pictures of blacks with violent crimes — even in some cases where crimes were not committed by blacks, they misidentified the perpetrator as an African American.

Defense attorneys always play hard on victims’ prior misconduct, bad behavior or any criminal conduct. The Grant case would likely be the same; early press reports repeatedly mentioned Grant’s alleged criminal record. This feeds into the stereotype of “bad-behaving” blacks, and the idea that the victim is somehow responsible for the officer using deadly force.

The biggest obstacle of all is the blurred standard of what is or isn’t acceptable use of force. It often comes down to a judgment call by the officer. In the Rodney King beating case in 1992 and again in the Sean Bell killing in New York City in 2007, defense attorneys turned the tables. They painted King as the aggressor, claiming that the level of force used against him was justified. In the Bell case, officers claimed that Bell and his companions were trying to run them down and they feared for their lives.

Convicting the cop who allegedly killed Grant, or any cops who wantonly kill, is a colossal task for even the most diligent prosecutor. The Grant case will be no different.

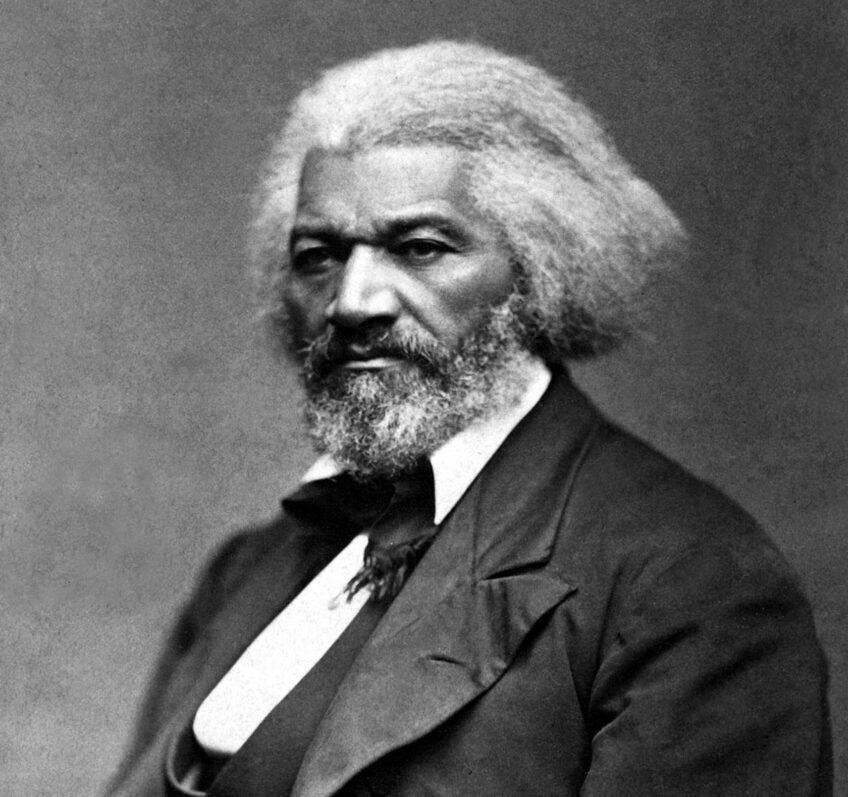

Earl Ofari Hutchinson is a syndicated columnist, author and political analyst.