NEW YORK — Emerging from the foyer of a former rectory in the East Village, Tommy Walker looks up and down the street.

No talent in sight.

The interviewer is somewhere down the block, smoking a Partagás. The interviewee is en route from uptown, picking up a coffee along the way. No reason to panic. At some point soon, the Cuban cigar will converge with Starbucks, and fusion will occur inside the converted parsonage.

Two things rarely stop working in Walker’s world — his mouth and his feet. Cell phone pocketed, the film producer takes off on a brisk pace down Second Street toward First Avenue, talking about his work on “The Black List,” a compelling video portrait series of prominent African Americans.

Volume 1 of the acclaimed documentary debuted during the Democratic National Convention last August. Volume 2 airs Feb. 26, at 8 p.m., on HBO.

“It wasn’t so long ago, I was out of this business,” says Walker. “But they just keep pulling me back in.”

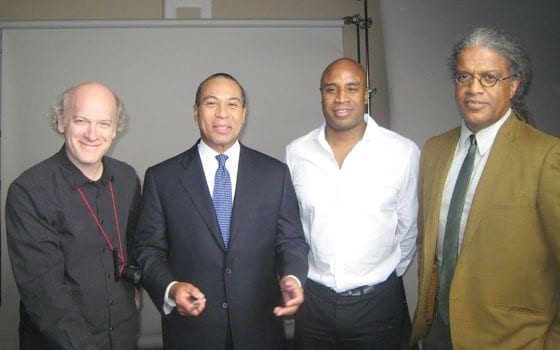

As executive producer of “The Black List,” Walker drew on wide-ranging contacts in the arenas of sports, politics and entertainment to muster an A-list of black celebrities to share their stories and insights in highly personal segments filmed by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, whose large-format photographs have appeared in the pages of Vogue and Vanity Fair, as well as on museum walls all over the world.

The filmed interviews take place straight to camera, with a monochromatic backdrop and a single light, recreating in video the distinctive look of Greenfield-Sanders’ award-winning still portraits. Whether it’s Colin Powell, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar or Suzanne de Passe, the subject talks directly to the audience, responding to the comments and questions of the unseen interviewer, radio host Elvis Mitchell, who prods, cajoles and flatters from behind a separate camera.

The effect is startling — convivial, close and compelling — and a tribute to the skills of Mitchell and Greenfield-Sanders.

Before being recruited to work on “The Black List,” Walker produced and co-directed “God Grew Tired of Us,” a 2006 documentary following the lives of a group of refugees, the “Lost Boys of Sudan.” The film, narrated by Nicole Kidman and executive produced by Brad Pitt, won the Sundance Film Festival’s 2006 Grand Jury Prize.

“People remember your last film,” says Walker. “You have to be ready to do something else.”

You’d expect nothing less from someone who makes documentaries with a social conscience — one of the toughest genres in the business. Who wants to bankroll them? Produce them? Air them?

Yet that’s been the main focus of Walker’s work.

The University of Virginia history major began his career doing postproduction for the “National Geographic Explorer” series in 1985. In 1991, he joined media gadfly Danny Schechter (“The News Dissecter”) as production manager for the PBS documentary, “Mandela In America,” which followed the African National Congress leader on his triumphant sprung-from-prison tour to the U.S., including a rollicking stop on the Hatch Shell before 500,000 people, where he danced with Winnie to Hugh Masakela’s wailing trumpet.

In 2004, Walker produced the Emmy-nominated, feature-length documentary “With All Deliberate Speed,” a thoughtful if sometimes bleak examination of the impact of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision 50 years after future Justice Thurgood Marshall successfully argued the school segregation case in front of the Supreme Court.

The theme of justice resonated throughout Walker’s childhood. His father, the late John T. Walker, was the first black bishop of Washington, D.C., and a close friend of Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

Walker attended St. Albans School on the grounds of the National Cathedral, perched along the heights of Wisconsin Avenue and overlooking the more secular precincts of Georgetown and the reclaimed swampland of official Washington.

In an environment saturated with lawyers and politicians, Walker found himself gravitating to the media. He worked for a summer at D.C.’s ABC affiliate, WJLA-TV, before graduating and moving to Los Angeles in the mid-1980s, where he honed his video and audio production skills on the sets of such shows as “Bustin’ Loose” and music videos like Bobby Brown’s “My Prerogative.”

“I woke up one day and I wasn’t sure where I was taking my experience,” says Walker.

A turning point occurred in June 1989, when he travelled with his father to Honduras, the poorest Spanish-speaking country in the Western Hemisphere, to make a documentary about conditions there. Soon he was covering elections in Central and South America, working on PBS’ news magazine, “Rights and Wrongs,” and doing commercial work in New York for Toyota, Daimler Chrysler and Hewlett Packard to keep creditors at bay.

For “The Black List,” Walker choreographed interviews and managed production day-to-day — shipping equipment, hiring crew, and rarely, if ever, getting off the phone.

“Compared to filming in Sierra Leone, this was relatively simple,” laughs Walker.

The conversation is interrupted by the wafting odor of Cuban tobacco. Elvis Mitchell strolls up. A taxi stops, and environmental activist Majora Carter steps out. Time to work.

“You know,” says Tommy, stepping across the marble threshold, “the question you never get used to is, ‘What are you doing next?’”