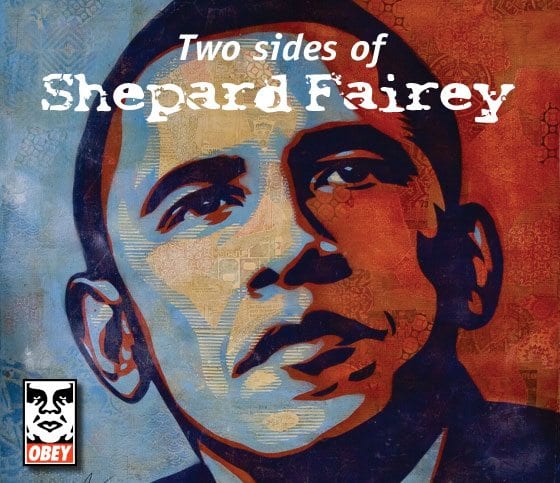

From his humble beginnings plastering images of Andre the Giant on street signs to his lofty perch as the creator of arguably the most iconic image of President Barack Obama, Shepard Fairey (below) has made his name by pushing boundaries. (Top: “Obama HOPE,” 2008, courtesy of Obey Giant Art; Inset: “Obey Icon Pole,” 2000, courtesy of Obey Giant Art; Above: Portrait of the artist, courtesy of Obey Giant Art)

| Pieces like 2007’s “Guns and Roses Stencil” exemplify Fairey’s penchant for drawing from the visual language of dissent, protest and pop culture, borrowing from forms like propaganda posters. (Image courtesy of Chloe Gordon) | In pieces like 2004’s “Obey Tupac Blue,” Fairey showcases his gift for making iconic images of figures who are icons themselves, transforming familiar photographs into spare, modernist distillations. (Image courtesy of Obey Giant Art) | The 2007 mixed media mural “Two Sides of Capitalism: Good” exemplifies Fairey’s knack for subverting familiar iconography for his own purposes. In this case, he infuses the dollar bill, one of the central figures in American capitalism, with populist slogans like “Power to the People” and “Manufacturing Dissent,” alongside his trademark Obey Giant image. (Image courtesy of Jonathan LeVine Gallery) |

Shepard Fairey gained early fame from his image of wrestling legend Andre the Giant, still peeling on traffic signs, derelict buildings, utility boxes and billboards throughout the world.

In 2008, Fairey traded irony for advocacy, creating the unofficial poster that became a defining image of Barack Obama’s campaign. Appealing to mainstream and counterculture voters alike, his poster spread with viral speed, mobilizing participation in the Super Tuesday elections.

Now, a year later and just weeks after the inauguration of President Obama, the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) is hosting Fairey’s first museum retrospective, “Shepard Fairey: Supply and Demand.”

Days before its Feb. 6 opening, Fairey was interviewed on “The Colbert Report,” “Charlie Rose,” and National Public Radio’s “Fresh Air.” In Boston, Mayor Thomas M. Menino had his picture taken with Fairey before a 20-by-50 banner installed by the artist on a side of Boston City Hall. The banner is one of 17 outdoor works commissioned by the ICA to accompany the show.

As an artist who regards his Andre postings as a form of dissent as patriotic as the Boston Tea Party, Fairey might have expected an unalloyed welcome here.

But en route to the ICA’s sold-out opening night party where he was to be a guest DJ, Fairey was arrested by Boston police on a graffiti charge from 2000. Released on personal recognizance, he spent last Monday at district courthouses in Brighton and Roxbury. Meanwhile, in Manhattan, Fairey’s lawyers were filing suit against the Associated Press, challenging its claim to compensation for the AP photograph that he pulled off the Internet as the basis for creating his campaign poster.

Testing boundaries is all in a day’s work for Fairey, whose unauthorized use of public space to post his art had already earned him 14 prior arrests for vandalism.

Heir to an artistic tradition that includes Marcel Duchamp’s 1919 reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” with a goatee and, 40 years later, Andy Warhol’s silkscreens of Campbell’s soup cans, Fairey samples the images of others’ like a DJ mixes tunes. He seldom cites sources, arguing that he transforms his borrowings into new images that are protected by fair-use exceptions to copyright law.

From stamp-size stencils to refined, large-scale works from private collections and museums, the 244 works on view at the ICA until Aug. 16 follow Fairey’s own 20-year campaign that started with Andre the Giant.

Although organized by themes such as music, portraiture and propaganda rather than in chronological order, the exhibition shows how far Fairey has gone with the modest, widely available tools of street art that inspired him as a teenager in Charleston, S.C.

He blends the do-it-yourself ethic and fast, low-budget devices — stencils, stickers and screen-printing — of skateboard graphics, punk T-shirts and album packaging with the images and tactics of corporate advertising and propaganda.

The works on view are a sort of cultural history. He draws from the visual language of dissent, protest and pop culture, borrowing from the styles of early Soviet Constructivist propaganda, Works Progress Administration posters of the ’30s, World War II patriotic signs, ’50s Americana, ’60s psychedelia, and images from the wars in Vietnam and Iraq.

In 1989, while a student at the Rhode Island School of Design, Fairey stenciled the face of Andre the Giant onto stickers, T-shirts and posters. He described the experiment in street art as “a total goof at the time.” But the enigmatic image caught on. Others joined him in pasting it throughout Providence and before long, posting their own bootleg versions. In a pre-Web form of viral marketing, a grassroots social network turned the image from a secret handshake among insiders into a global street-art phenomenon.

A few years later, Fairey abstracted Andre’s face and combined it with the word “Obey.” He was inspired by John Carpenter’s 1988 camp horror movie “They Live,” in which a drifter (played by another popular ’80s pro wrestler, “Rowdy” Roddy Piper) finds a pair of sunglasses that lets him read the subliminal messages displayed on billboard ads, which command viewers to “Obey” and “Consume.”

“It was really stupid, but had a profound premise,” the boyishly handsome Fairey, 39, said during an exhibition preview, wearing a T-shirt, jeans and sneakers. “The movie crystallized a lot of what I felt but didn’t know how to convey succinctly.”

While making mock use of propaganda to counter it, the Obey project provided Fairey with the means to take charge of his message and medium.

“I want to communicate with as many people as possible,” said Fairey, “not just through galleries and museums.”

In an interview with show co-curator Emily Moore Brouillet included in the exhibition catalog, Fairey says, “If my manifesto would be condensed to two sentences, they would be: empower yourself and question everything.”

The image of Andre quickly became a kind of counterculture “Big Brother” and, in the process, built a community and brand for Fairey. The Obey Giant Web site (http://obeygiant.com) is a merchandising hub for Obey wares, which range from $7 sticker packs and signed limited-edition posters to a fashion accessories line.

With or without the word “Obey,” the image is visible in just about every work on view. In the lovely stencil collage “Monkey Pod Tree” (2008), dime-size stars with Andre’s face dangle off branches like Christmas tree ornaments. A star with Andre’s face hovers in the background of “Obama HOPE” (2008), a mixed media stencil collage on paper that commands the show. An identical version from the same stencil is in the permanent collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

Fairey enjoys the crossover of his commercial, street and fine art endeavors.

“If they work hard, individuals can create their own Utopian way of doing things within capitalism,” said Fairey, who with his wife, Amanda, has two young daughters. The couple runs a graphic design company at Obey Giant headquarters in Los Angeles that has such clients as Virgin and Honda.

Just as Warhol duplicated silkscreens of soup cans and celebrities in his studio, which he called his “Factory,” Fairey employs a system of mass production that keeps “supply and demand” high.

Fairey’s images are building blocks that he “tiles up” to create larger pieces or expands in size and complexity. His signature palette of red, off-white and black had its start when, as a teenager, he depended on a cheap copying machine. Since then, the limited palette has served him well. Fewer colors mean fewer steps in the printing process, and the spare use of color increases the impact of his carefully designed stencils.

The red gains seductive power in alluring, abstracted figures of veiled women set in richly textured collages that blend art deco wallpapers and vintage news clippings. In the hand-painted, silkscreen collage “Mujer Fatal” (2008), ads for chic ’30s outfits are visible behind a glamorous female figure in guerrilla garb.

Fairey prints the same images on a variety of media. Elegantly simple black and white renderings on wood, metal and record album covers hold their own near a row of skateboard decks illustrated with exuberant, high-gloss graphics. Fairey even presents his designs in rubylith, the red acetate film that is used in the first layer of a printing process. A wall of such prints includes a dreamy image of musician Lou Reed.

Like Warhol, Fairey makes iconic images of people who are themselves icons. He transforms familiar news photographs into spare, modernist distillations, stripping out extraneous details. On view are images of influential figures from the past 50 years, including Fidel Castro, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Muhammad Ali, and the linguist and dissident Noam Chomsky. In another gallery, a parody of a patriotic poster, “Obey Bush One Hell of a Leader” (2004), presents former President George W. Bush as a vampire.

When Fairey depicted Barack Obama, he portrayed the candidate as a forward-looking leader who could reconcile red and blue states of mind. Both patriotic and cool, the portrait as well as its viral method of distribution suited the populist, grassroots spirit of the Obama campaign. Fairey printed a few hundred and released the image on his Web site. Within days, thousands were in circulation.

What will Fairey do next? His 20-year Obey Giant campaign appears to have run its course. An air of finality hangs in the last gallery along with his 10-by-16 murals, which incorporate images that started as stamp-size stickers. Whatever follows, Fairey has already made an indelible mark. Speaking of his Obama poster, Fairey said, “I regard it as justification for my previous 20 years of mischief.”

A map of Fairey’s 17 commissioned outdoor works is available through the ICA at http://www.icaboston.org/exhibitions/exhibit/fairey/outdoor/. Those interested can also join the curator for a Sunday bike tour of these sites on May 17 or June 28.