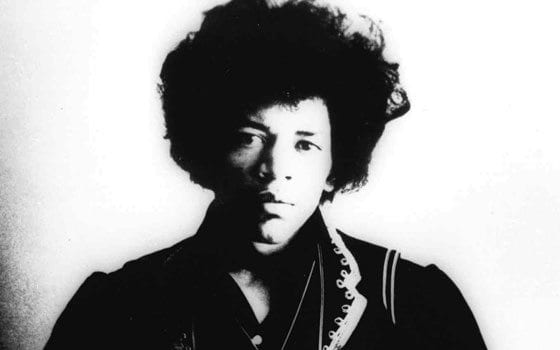

Of all the muddy, drug-fueled images of Woodstock, none stands out more than Jimi Hendrix playing “The Star-Spangled Banner.” It was an eerie solo delivered on the morning of Aug. 18, 1969, complete with amplified feedback designed to mimic the sounds of falling bombs and screaming jets, speeding ambulances and human anguish.

That Woodstock became an iconic symbol of the nation’s angst over the Vietnam War and a generation’s rejection of mainstream values is a matter of little debate. But it remains a mystery that Hendrix would play the national anthem that Monday morning to a crowd that had thinned to about 40,000 from the estimated half-million who ventured to upstate New York. Scheduled to perform at 11 p.m. on Sunday night, Hendrix didn’t make it to the stage until about 8 a.m. the next day.

Hendrix had played the song countless times before, including at the Royal Albert Hall in London and the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles. But at Woodstock, the rendition took on an entirely different meaning. To some conservative critics, the distorted version of the national anthem was tantamount to heresy.

Shortly after the concert, Dick Cavett, one of the most popular talk show hosts of the 1960s, asked Hendrix about the controversy.

“I don’t know, man,” Hendrix replied. “All I did was play it. I’m American, so I played it. I used to sing it in school. They made me sing it in school, so it was a flashback.”

Cavett quickly interrupted the interview and suggested that Hendrix’s version was “unorthodox.”

Hendrix respectfully disagreed.

“I didn’t think it was unorthodox,” he said. “I thought it was beautiful.”

Beautiful or not, it was clearly American — at least to Hendrix.

“We’re all Americans,” Hendrix said during a press conference three weeks after Woodstock. “… It was like, ‘Go America.’ We play it the way the air is in America today. The air is slightly static, see.”

Part of that static was the nation’s complicated history on race. At the time, Hendrix was the only black musician with an enormous white following. Though he performed for years throughout the Deep South, in the mostly black clubs dubbed the “Chitlin’ Circuit,” as a sideman with the likes of Little Richard and the Isley Brothers, Hendrix had to go to London to establish himself as a solo artist.

When he returned, with millions of mostly white rock ‘n’ roll fans enthusiastically considering him one of their own, he was not as embraced by the black community, in part because Hendrix was a reluctant spokesman for black causes.

He spoke with his guitar.

According to biographer Charles R. Cross, Hendrix was suspicious of all analyses that saw race as the eye of America’s hurricane. And he was more suspicious still of black organizations that sought to recruit him, particularly the Black Panthers, a group that Hendrix considered to be prone to violence.

In an interview with David Henderson, author of the biography “’Scuse Me While I Kiss the Sky,” Hendrix got right to the point.

“Black kids think the music is white now, which it isn’t,” Hendrix said. “… The argument is not between black and white; that’s just another game the establishment set up to turn us against one another. … The easy thing to cop out with is saying black and white. That’s the easiest thing. … But now to get to the nitty-gritty; it’s getting to be old and young — not the age, but the ways of thinkin’. Old and new, actually. … most people are sheep. This is the truth, isn’t it? That’s why we have the form of the Black Panthers and some sheep under the Ku Klux Klan. They are all sheep.”

One thing is clear: Hendrix was no one’s sheep. Despite being kicked out of the 101st Airborne Division for reasons that range from being uncontrollable and requiring constant supervision to his feigning having homosexual fantasies, he still remained patriotic. And when pressed, he remained in tune with blacks, including the Black Panthers.

“I naturally feel a part of what they are doing,” Hendrix told an interviewer. “But everybody has their own way of saying things. They get justified as they justify others, you know; in their attempts to get personal freedom. That’s all it is.”

According to biographers, Hendrix dedicated songs to soldiers on both sides of the revolution — those fighting for peace and those fighting in Vietnam jungles.

Pete Townshend, the legendary guitarist of The Who, got it right when he told Hendrix biographer Charles Shaar Murray that Hendrix was too complicated to put in any one category. Townshend, who admitted his own discomfort around black musicians and the blues, said Hendrix was angry and once called him “a honkie” after a backstage spat.

“He’d been in the black milieu as the sideman for this musician and that musician, and this was his chance to not only draw himself out of the mire of mediocrity but also do something for the black cause,” Townshend said. “… There was a tremendous sense of him choosing to play in the white arenas, that he was coming along and saying, ‘You’ve taken this, Eric Clapton and Mr. Townshend, you think you’re a showman. This is how we do it. This is how we can do it when we take back what you’ve borrowed, if not stolen.’”

Bobby Womack had a different perspective. Hendrix “was tryin’ to fit in on his side of town, but it wasn’t his side of town,” Womack told Murray.

“He needed to be in another place … man, when he got to Europe he got with people that was like him, they was his family. I was glad that he found a place,” Womack continued. “And then a lot [of] blacks started sayin’ how it’s terrible that he had to go the white side to make it … All these [black] people would come out of the woodwork: ‘He worked for me and I kicked him out.’”

With Hendrix, there’s no telling what was fact or fiction. But on that morning, when Woodstock was winding down, Hendrix brought a raucous, debauched crowd to a patriotic halt.

“It was the most electrifying moment of Woodstock, and it was probably the single greatest moment of the sixties,” gushed New York Post pop critic Al Aronowitz. “You finally heard what the song was about, that you can love your country but hate your government.”

A little more than a year after Woodstock, Hendrix died in London under mysterious circumstances. He was 27 years old.