Ex-cons battle overwhelming obstacles, odds

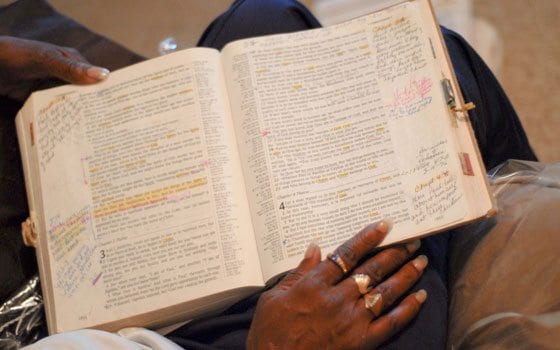

Roxbury native Pamela Henderson holds her favorite Bible — the first one she had during her years in prison — heavily scribbled in from close, repeated study. For ex-convicts like Henderson, the path to re-entry into mainstream society is littered with temptations and roadblocks. (Daniela Caride photo)

| Hundreds of activists jam the entrance to the State House during a September 2007 rally asking legislators to change the laws that govern the Criminal Offender Records Information system. (Banner file photo) | Clarence Buggs speaks at a SPAN Inc. event where he received a certificate for his accomplishments in life after being released from prison. Buggs, 57, learned how to upholster furniture while an inmate at MCI-Norfolk in the 1970s. (Daniela Caride photo) | Christina Mercogliano sits at the East Boston sober house where she now lives. While the 25-year-old has nine years of experience in the retail industry, she says prospective employers recoil at the sight of her criminal record. (Daniela Caride photo) |

Christina Mercogliano, 25, has nine years of retail experience. You name it, she’s worked it — everything from the cash register to stocking shelves to overnights in shipping and delivery.

But none of that counts these days when she goes out on job interviews. When potential employers see her criminal record — which includes multiple assault, battery and armed robbery charges — they don’t answer her follow-up calls.

“They look at me like I’m a menace to society,” says Mercogliano. “A lot of people believe you should live hung for your crime for the rest of your life.”

Released from prison last July, Mercogliano now lives in a sober house in East Boston. Her life has become a symbol of a well-known vicious cycle.

Life without a job is hard enough. Life without a job and with a criminal record is even worse.

“It’s very stressful,” she says. “It’s overwhelming even today.”

Mercogliano had been in prison for 18 months. In addition to food and rent, she must pay monthly parole and probation fees while battling a now-controlled heroin addiction that once dragged her into crime.

Even with all that on her plate, Mercogliano is luckier than most offenders leaving prison in Massachusetts. She applied for membership in SPAN Inc. while still in jail, and the nonprofit organization not only found her a sober house, but also paid her rent for five weeks. She attends meetings, gets psychological support, looks for jobs and eats at SPAN Inc.’s downtown Boston headquarters.

“If it wasn’t for SPAN, I’d probably still be sitting in jail looking for a place to go, ’cause it’s so hard to get into a program,” says Mercogliano.

The problems

Getting a job is only one of a series of challenges people like Mercogliano face, says Lyn Levy, president and founder of SPAN Inc., an organization that helps ex-prisoners reenter mainstream society. Levy says ex-convicts must reinvent themselves and unlearn many of the habits they acquired in prison.

“You don’t get a free ticket when you walk out of prison,” says Levy. “You have to work … take care of yourself … feed yourself, put clothes on your back. You don’t have any money or job. You don’t know how to do those things.”

And ex-inmates must face other challenges, she says, like getting used to deciding what to dress, eat and read; being a good daughter, father or neighbor; taking the steps to get an education, a loan or health insurance.

The first challenge, she says, is “to figure out their new lives.”

“People come out with no money [and] … with not a lot of support,” says Levy. “There’s a good bit of stigma attached to being an ex-offender. Prison is a very restricted and tense atmosphere where folks are not encouraged to make decisions.”

One major hurdle for many ex-convicts is overcoming drug addiction. According to Levy, at least 75 percent of people incarcerated have been through some kind of substance abuse.

Clarence Buggs, 57, is one of them. A cocaine addict, Buggs said he learned how to upholster furniture in 1975 while incarcerated at MCI-Norfolk on an armed robbery conviction.

When he was released six years later, he had a little money saved up that he earned working on the inside. He quickly found an upholstery job in downtown Boston and rented a studio in Back Bay.

“I could handle paying bills and having my own apartment and making sure all the bills were kept up and all that,” says Buggs. “The only problem I really had was my education and drugs. That was my downfall.”

Buggs was able to keep his life together, even though he continued to use cocaine and crack, for 12 years. But eventually, he lost control of his addiction again. Always late for work, he lost his job.

“Everything was nice, but I didn’t take care of my drug [addiction],” he recalls.

Though Buggs did not go back to crime, soon he was panhandling and sleeping in shelters. The next two years, Buggs says, he spent “getting high 24/7, with no work and no nothing.”

Mary Nee, executive director of hopeFound, the third-largest homeless service organization in Boston, says that about 80 percent of the homeless people that hopeFound serves have some form of addiction.

Because it’s “quite typical” that a large percentage of people end up having criminal records when they have long standing addictions, Nee estimates that 50 percent of the 3,500 people who use hopeFound services every year have a criminal history.

“What we find working with homeless individuals is [that] in a large number of cases the criminal records are all related to their addictions,” says Nee. “So it’s not unusual that … someone who has been clean and sober for a period of time … [has] no interaction with the criminal justice system. All of their interactions occur during this time that they are active.”

It was 1994 when Buggs got arrested again for a robbery he says he didn’t commit. Either way, he was convicted and sentenced to another eight years in prison.

“I was angry about someone saying I did something I didn’t do, but I blame myself in a way because I had my choices,” he says. “I needed help, but I didn’t know how to get any.”

Treatment, says Levy, is often difficult to find in Boston. Residential treatment programs “are full and bursting,” she says. “So being able to come out of prison into a residential setting is very, very difficult.”