Thomas Atkins, Boston’s first black at-large city councilor, who faced off against school busing opponents as an NAACP leader in the 1970s, has died. He was 69.

Atkins, a Harvard Law School graduate, died last Friday at a nursing home in Brooklyn, N.Y., after struggling for years with the degenerative muscular disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, better known as Lou Gehrig’s disease.

Atkins is remembered for his tireless fight against discrimination and his unyielding battle for equal education.

His description of power is one of his more memorable social observations. Power was colorless, he once explained: “It’s like water. You can drink it or you can drown in it.”

“He was clearly the most brilliant and insightful civil rights lawyer, both in and beyond Boston, to take on the challenges of school desegregation,” Ted Landsmark, who worked with Atkins in the late ’70s as a lawyer at Atkins’ Boston law firm, Atkins and Brown, told the Boston Globe.

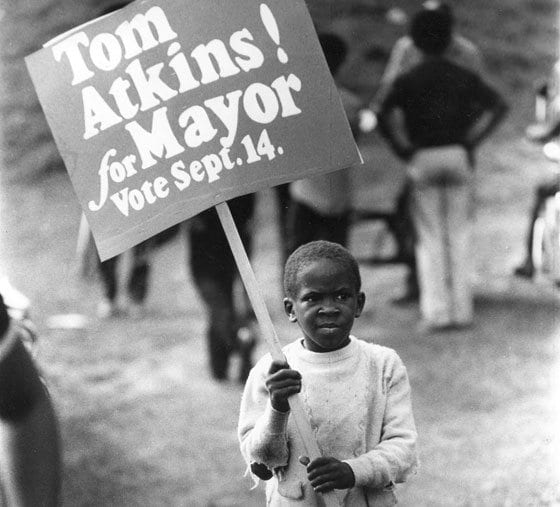

Atkins was a Boston mayoral candidate in 1971. After his defeat, he became the first black to hold a state cabinet post when he became secretary of communities and development under Governor Francis W. Sargent.

His commitment to civil rights and equal education was unwavering. He served as executive secretary and president of Boston’s NAACP chapter and as NAACP general counsel in New York.

In a 1994 interview with the Globe, Atkins was particularly blunt. Court-ordered busing, Atkins said, “forced open the lid on Boston’s poorly kept, nasty little secret, which was citywide racism … Members of the [Boston] School Committee placed their own political salvation over the welfare of the city or the school system or the schoolchildren.”

Thomas Irving Atkins was born in Elkhart, Ind., the son of Norse Pierce Atkins, a Pentecostal minister, and Lillie (Curry), a domestic.

He was the first black student body president at Elkhart High School. He made Phi Beta Kappa at Indiana University, where he was the first black class president and first black student body president at a Big 10 school.

“He spent his entire life pursuing education for everyone,” Todd Atkins, the deceased’s oldest son, told the Boston Herald. “His family sacrificed for him, and I think he wanted to give back.”

Atkins was a councilor from 1968-1971. In an interview with the Herald looking back on that time, he remembered desegregating the public schools as a turning point.

“It was an event of such significance and power it transformed the politics of the black community,” Atkins said. “It created a cadre of people who know how to get things done.”

In addition to his sons and former wife, Atkins leaves a sister, Anna Jane Millsaps of South Bend, Ind.; a brother, Pierce, of Elkhart; three granddaughters; and one great-granddaughter.