How a personal tragedy inspired a unique creative legacy

|

|

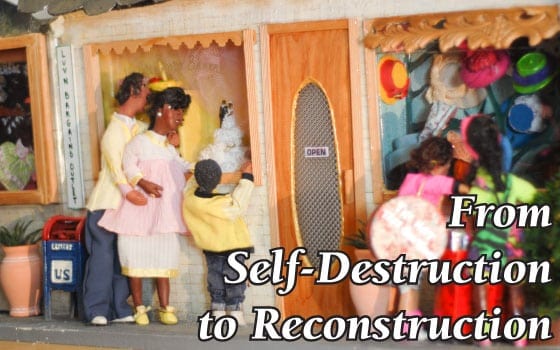

Nearly 20 years ago, Deborah Cornin was the victim of a horrific home invasion, and rape. One thing set her off on the road to recovery: Making dollhouses depicting scenes of African American life, like the one above. (Daniela Caride photos) | Though Dorchester artist Deborah Cornin draws inspiration for her dollhouse scenes from her own youth, some who view her pieces find themselves transported back to their pasts. “It was just like [Cornin] was looking through my eyes when she created these things,” said Patricia Morehead, a 59-year-old retired police officer from Illinois. (Daniela Caride photo) |

Sometimes tragedy has to strike in order to make us do greater things, says Deborah Cornin.

It struck her at 3 a.m. one night in 1989, when a man scaled three porches and broke into her Dorchester home through the roof. The intruder covered Cornin’s head with a sheet, beat her and raped her. She never got to see his face.

“I was a nice church girl,” she remembers. “But life happens and it hurts.”

Her life came to a halt. Leaving the house only to go to work and to church, Cornin sunk into depression and prayed to God every day for help.

“I kept thinking, ‘I can’t do one more thing,’” recalls Cornin. “So I stopped answering the phone, I stopped belonging to things. I just stopped.”

Eventually, the discovery of a unique gift got her moving again: She had the talent for making dollhouses depicting scenes of African American life.

It may sound like an odd jumpstart to some. But it got Cornin to put one foot in front of the other, and as she recalls, that was all that mattered.

“Like you need water, I needed to do this,” she says. “God gave me certain words and He said to me, ‘I’m gonna show you how to move from dysfunctional to functional, from self-destruction to reconstruction, from grief to relief.’ And that’s what this represents.”

Now 52 years old, Cornin has built 28 such dollhouse scenes. She exhibited her work for the first time at Harambee: The 2008 Black Doll Collectors Convention, held in Mansfield in May. The convention confirmed that in addition to her work’s personal value, the scenes also had financial value — Cornin’s pieces were appraised with an initial bid of $10,000 each.

But only God knows the final price. Cornin says she is determined not to sell them.

“They are my children’s legacy,” says Cornin, sitting in her workroom at her home in Dorchester, surrounded by black dolls in miniature beauty parlors, schools, restaurants, churches and homes.

She says she started making black dolls because they reflected her life experience. Most of the people at the schools and churches she attended were black, as is her family.

Her family is the main source of inspiration for each of the scenes in her dollhouses, a collection named “Luv N Life Creations Possess the Family Affair.”

She cherishes Christmas memories, like her grandparents singing spirituals in the kitchen while cooking and her grandmother preparing Jell-O — three colors in one bowl, Cornin recalls.

During those meetings at her grandparents’ house, food and love abounded, and gifts were scarce.

“The happiest time for me was when I was a kid, and not because we had stuff. It was because we had each other,” says Cornin. “We were poor, but we didn’t know we were poor, because the other kids had the same nothing.”

Growing up in the 1960s, Cornin says she didn’t need toys much. She had her imagination. With her foster cousin who lived next door, for instance, she planned how “to get all those people out of the TV set” to play with them.

“There’s got to be a door into this TV, and if you can just get in there, you can get those people out,” she remembers saying.

When her grandfather threw the TV out, she couldn’t understand why people were not inside the big old tube. Her cousin thought they must have moved.

“But then we thought, ‘There’s some people in the radio, too’ and I thought we could get them out,” she recalls, laughing. “So we were figuring out how to cut the screen of one of those big old consoles.”

Cornin’s dollhouse work also brought back fond memories in other people. Patricia Morehead, 59, a retired police officer from Illinois who has been a dollmaker for 16 years, says Cornin’s dollhouses immediately reminded her of some very special moments.