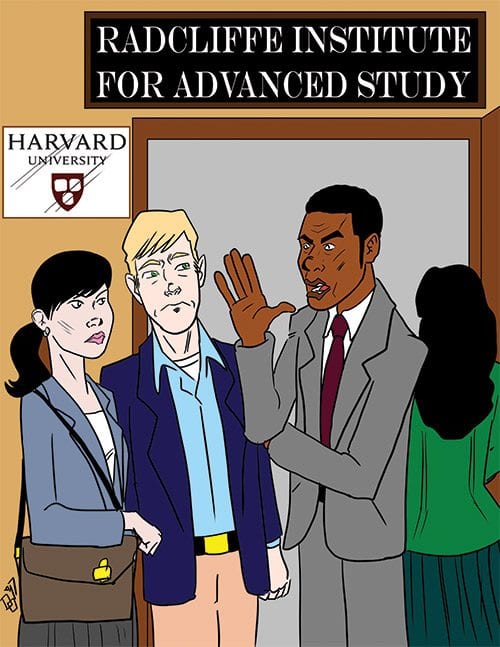

The Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study recently sponsored a well-attended conference entitled “Universities and Slavery: Bound by History,” to discuss the complicity of academia with slavery in America. When considering slavery, one’s first thought is the Civil War and plantation owners growing rich from forced labor. The nation’s exalted institutions were considered to be far removed from such a depraved practice. However, with the growing recognition of the involvement of esteemed universities in slavery, it is becoming more apparent that slavery was more extensive than was generally believed. Ironically, academia has become a major battleground for opposition to affirmative action.

New England did not have an agricultural economy that required a large number of slaves, but several Yankee families were prominent in both the slave trade and the development of local universities. John Brown, an 18th century Providence banker, financed slave traders and was also a founder of Brown University.

Ruth Simmons, the former president of Brown University and the daughter of a black Texas sharecropper, initiated a program in 2003 to investigate Brown University’s connection to the slave trade. This effort launched a general interest in academia’s involvement with slavery. Numerous published accounts established academia’s complicity. One of the most disturbing stories is that Georgetown University sold its 272 slaves in 1833 to cover the institution’s cash deficit.

Harvard also was not innocent. The university countenanced the discredited white supremacy work of biologist Louis Agassiz, and the Harvard Law School accepted financial contributions from Isaac Royall Jr., a planter in the West Indies who was known to be extremely cruel to rebellious slaves.

With such a history of involvement with slavery, it is appropriate for academic institutions to support the affirmative action policies to provide educational opportunities for the descendants of former slaves. But now there is a growing protest from those who view such policies as discrimination against whites. With a renewed awareness of the pervasive slavery in America, it is a good time to review the concept of affirmative action, especially as it applies to academia.

The modern policy of affirmative action began in 1961 with President John F. Kennedy’s Executive Order 10925 requiring government contractors to assure “… that applicants are employed, and employees are treated during employment without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin.” This was merely a prelude to the provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Implicit in affirmative action policy then was that the applicant is qualified for the job he or she seeks. Nonetheless, whites protested that their jobs were being unfairly taken by unqualified minorities. There was also a mistaken belief among some blacks that they were entitled to the job because of past racial discrimination, regardless of their qualifications.

Some of the most heated affirmative action battles have been over admission to colleges and universities. The Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study conference will have been socially successful if professors and college administrators were induced to strengthen their commitment to support a racially diverse nation with college campuses that reflect this ideal.