Through Feb. 26, Northeastern University’s Gallery 360 is exhibiting five powerful paintings by artist Marilène Phipps-Kettlewell. Known for her poems, Phipps-Kettlewell’s artwork reveals a stirring portrait of Haiti, her birthplace and home until she was ten years old. She grew up during the violent rule of President François Duvalier (Papa Doc), and her work reflects the scarred nation and people she left behind.

On the web

For more information about Gallery 360, visit: www.northeastern.edu/art/category/gallery-360

For more on Marlène Phipps-Kettlewell, visit: http://marilenephipps.com/about/index.php

Phipps-Kettlewell’s paintings are marked by bold colors and chunky, textural brushstrokes. Her simple forms are alive with energy, much like the Haitian countryside she longed for in later years held a natural vibrancy that a metropolis lacks. “At the Immaculate’s Shrine” features a group of figures raising their arms to praise a statue of the Virgin Mary. Though the stonework and flowers of the structure holding the statue are quite detailed, the figures are assembled with simple geometric blocks of color. This could be a reference to religion’s ability to unify large groups and simplify individual differences in the face of something larger.

“Teramen” is more visually complex. Four presumably family members stand in a line against a wall in their home. None of the figures engage with each other. Even those looking at the viewer have a slightly glazed-over look in their eyes. Teramen was an Athenian general during the Peloponnesian war, part of a radical faction that toppled the democratic government. This is undoubtedly a reference to Duvalier, whose iron rule destroyed many families, including this one. Perhaps they, too, have lost family members — and faith — under a militaristic government.

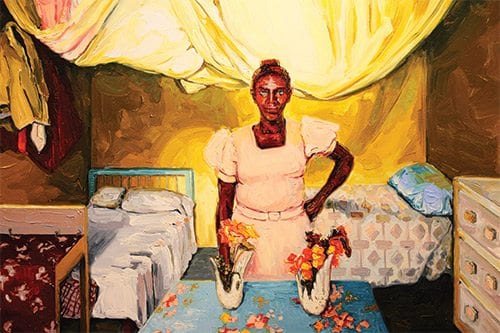

The show is small, comprising only five paintings. But the collective narrative tells a far greater story. “Saint Ursula’s Passion” centers on a black woman in a frilly pink dress. She’s in a domestic scene, with laundry hanging around what appears to be a bedroom. Her delicate garment and the flowers she has in hand evoke a stereotypical feminine, household setting.

Saint Ursula, in the Catholic canon, was one of eleven martyred virgins, killed by the Huns. The woman in this painting, however she’s dressed up, is no defenseless child. She confronts the viewer with a fierce glare, as though she may smash you over the head with the vase she’s arranging. This reframes the home as its own kind of battlefield, in which this dolled-up woman is a warrior. It’s certainly a timely display, coinciding with the Boston Women’s March last Saturday.

At first glance, Phipps-Kettlewell’s paintings appear to be bright, scenic paintings of life in Haiti’s countryside. But on further inspection they reveal the effect that Duvalier’s rule had, not only on the 60,000 Haitians who were killed during his time in office, but on those who were left behind.

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/NJ-H_1-713x848.jpg)