A common strategy used in the Old South to thwart the emergence of black defiance was to hold a terror lynching. The horror of a public hanging for the charge of being insufficiently obsequious quickly sent the message that complete subordination was expected. According to a 2015 report of a study by the Equal Justice Initiative of Montgomery, Ala., there were 4,075 such lynchings in 12 Southern states of the former Confederacy between 1877 and 1950. The Dylann Roof trial in South Carolina revives memories of those times.

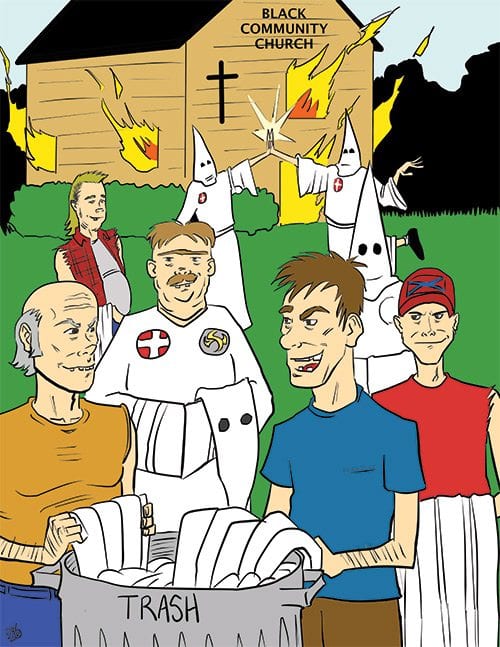

The concept of lynching did not suddenly end in 1950. Violent racial oppression primarily took a different form. Black males were disproportionately incarcerated for crimes even though there were a similar number of white perpetrators. Also, the great number of unarmed black men that have been killed by the police has incited a national protest. This history of violent racial oppression undoubtedly inspired Roof, a 22-year-old white youth, to massacre the minister and eight members of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, S.C.

Roof’s trial has begun, and it creates considerable controversy as did his mass murders. The prosecutor has no choice but to charge Roof with a capital crime. If found guilty, Roof could well be executed. But Roof has asserted that he will plead guilty to avoid the expense and emotional disruption of a trial if he can be guaranteed a sentence of life in prison. When the prosecutor rejected the offer, Roof then requested the right to represent himself at the trial. The judge granted this request, since there is little evidence that a mental defect impairs Roof’s capacity to defend himself.

In today’s socially changing environment, the prosecutor would have a political problem if he were to exonerate Roof from the possibility of execution. There have been 43 executions in South Carolina since 1985. Very rarely is a white person executed for killing someone who was not white. As long as murder is still a capital crime in South Carolina, how can a white youth evade that penalty for the massacre of nine black church parishioners?

The problem is that as counsel for the defense, Roof will have the opportunity to question the survivors of his mass murder, and thereby create considerable emotional distress. However, in an extraordinary humanitarian spirit, the survivors of Roof’s brutality have indicated their opposition to capital punishment, even if the criminal is their assailant.

The election of Donald Trump seems to have revived the hopes of white supremacists for their political reemergence. Congregants of Charleston’s Emmanuel AME Church maintain a more compassionate state of mind.