What Freedom Looks Like

Harvard exhibit examines equal rights images

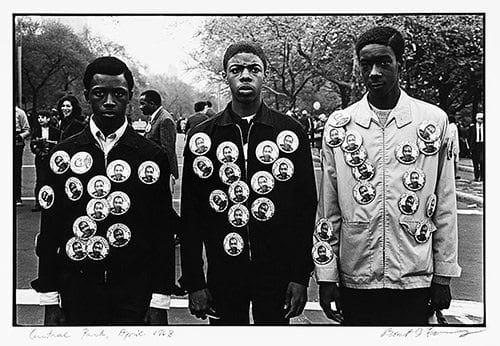

Vision and Justice: The Art of Citizenship,” on exhibit at the University Teaching Gallery at Harvard Art Museums through January 8, 2017, explores the relationship among art, justice and African American culture in the United States from the 19th through the 21st century. A small but impactful show, the images range from documentary photographs of the civil rights movement to more symbolic visualization of the continual struggle for equality.

Curator Sarah Lewis, an assistant professor in the departments of History of Art and Architecture and African American Studies, draws inspiration from Frederick Douglass, who spoke frequently about the power of images. Douglass was the most-photographed American of the 19th century and understood that in an increasingly media-centric world, being well-portrayed in pictures could mean the difference between respect and restriction. That idea becomes more forceful in our modern age of social media and 24/7 news cycles. “Vision and Justice” provides a peek into the depicted world of African Americans at pivotal points in racial history.

Some images are expected, perhaps even required, such as a photograph of a protest march to Selma and several portraits of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Others beg for a closer look. “Kitchen of a Farm Security Administrator’s Tenant Purchase Client, 1939” by photographer Russell Lee shows a woman with her back to us, standing in the corner of an all-white kitchen. The pose makes the subject anonymous against the white backdrop, perhaps a reference to her anonymity in a white-favored world. The photograph’s title further isolates her from us, describing the scenario in the most distancing way possible, prioritizing the space and introducing the FSA lessor before the female tenant.

One strength of the exhibit: the range of images. One wall is taken up almost exclusively by a large Kara Walker print. “African/American, 1998” shows the silhouette of a black woman scantily clothed and lying upside down on the white canvas. She wears a long beaded necklace and armbands that could be decorative bangles — or shackles. Walker’s signature cut-paper silhouette style is a reference to popular 19th century portraiture, typically favored by wealthy white patrons. The image is both elegant and jarring. Walker herself described the piece as “your essentialist-token slave maiden in midair.”

Glenn Ligon’s 1988 work “Condition Report” is a similarly minimalist yet powerful piece. The diptych features two prints with the words “I am a man” on them. This is a reference to placards used by black sanitation workers during their nonviolent protest for better rights in 1968 Memphis, Tennessee in 1968. The right-hand print of the duo has an overlay of condition comments on it, pointing out cracks, smudges and other wear and tear. These reflect both the deconstruction of the artwork and of the morale of the original protestors, who fought so long for so little.

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/NJ-H_1-713x848.jpg)