Davis Guggenheim’s documentary ‘He Named Me Malala’ offers hope, inspiration

Oscar-winning filmmaker Davis Guggenheim (“An Inconvenient Truth”) hits the screen again with the heartwarming and inspirational documentary “He Named Me Malala,” about Malala Yousafzai, the teenager who won last year’s Nobel Peace Prize. Through the film Malala and her family are able to share their story with the world in their own voices. Not only do we see Malala the activist, but we’re also given a glimpse into the daily life of the 18-year-old and her family — father Ziauddin, mother Toor Pekai and her two younger brothers Khushal and Atal — all of whom now reside in the U.K. after her 2012 attempted assassination by Taliban militants, who shot her in the head as she was returning home from school by bus.

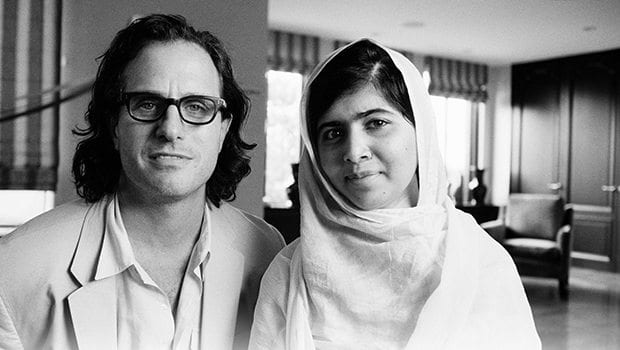

The director and producer of “An Inconvenient Truth” and the 2010 thought-provoking film “Waiting for ‘Superman’,” Guggenheim spent a year and a half with the Yousafzais, accompanying them throughout the globe. He’s on record calling the experience perhaps the greatest privilege in his life. Guggenheim recently spoke to the Banner about his first encounter with Malala and her family, what he learned about himself during the filming process and her relationship with her parents.

What was your first encounter like with Malala?

Davis Guggenheim: I remember I flew to Birmingham, England. I took a cab to her house, rang the doorbell. I didn’t know who I was going to meet. I may have been introduced to a few Muslim families but I’ve never really known any Muslim families, which is surprising. You sort of bring with it some of the baggage of information that you know.

She came to the door, answered it, and then I walked in. It was a kitchen, just like the kitchen I live in. It was kind of a fun, joyous family. She’s a very modest person. She’s very poised and in the moment, which is very, very surprising.

Was there any hesitation on their part in allowing you into their home and being with them and following them and showing the other side of her life?

DG: It wasn’t as much hesitation. I think part of them was like ‘Who is this guy — this guy with this long hair and looks very different from we do?’ They weren’t as familiar with what a documentary film is. They told their story before, but to journalists. And the New York Times did a short film.

But my process is very different. Very soon they opened up, and we became very close. There was a mutual trust that was built, which is really the core of a good movie.

The documentary took a year and a half to film. During that time, you’re traveling with them, you’re with them, and you’re experiencing everything that they are, first-hand. What did you learn about yourself during that time?

DG: You don’t think ‘Well, the filmmaker should be dispassionate.’ I like when movies play on me. It made me ask myself, ‘What kind of father I am?’ I have two daughters. I know I say they’re equal, but do I believe it in my heart? What are my sorts of subtle prejudices and how could I be like Zia? What could I do to make my daughters feel as powerful and give them that sense of agency that made Malala speak out?

I still don’t know what that is. The fact that it plays on me so much is good.

Where does Zia’s determination for Malala to be educated come from?

DG: Zia’s father was a cleric, but a cleric almost implies just a religious figure. I think he was also a teacher of ideas. Clerics are communicating the messages of Islam, [which] I think is part of it. I also think he was a student who was inspired. First, he had a stutter and knew he couldn’t become a cleric. Here’s an interesting thing. For a while he was inspired to live jihad, which means you’re dying for the faith, which is often misused by terrorists. Because he was so moved by people, he said this, ‘Let me die for Islam.’

Then, I think, as he became more educated, I think he had a few teachers who taught about Martin Luther King, and he started to learn this idea about human rights. For him and a small group of people where they lived, this idea of basic human rights was a profound thing. This idea that people deserved water, girls deserved a name, girls deserved an education. This became very meaningful for him.

The film focused on the relationship between Malala and her father but I wanted to know more about her mother. What is their relationship like?

DG: I think it’s important to know the difference between religion and custom. From where she was — and she’s a very traditional woman from Pashtun society — being on camera was immodest. I think some people read too much into that, that maybe she was pushed into the background, and that’s not the case.

She’s a very strong woman. She chose not to be in the movie as much. Towards the end she opened up a lot and loves the movie. At the core, for those who know Malala really well, she gets her passion and her sense of mission from her father, but her moral strength — and she is a very strong woman — and her spiritual strength come from her mother. Her mother is a very powerful woman.

Did you ever feel that you were being drawn into their lives and that you wanted to affect change yourself?

DG: It’s interesting. In some respects, the roots of documentary or journalism — journalists are supposed to be dispassionate, but I’m very passionate. I want to feel the emotion that I feel. I want the audience to feel the emotion I feel when I learn about these stories. That’s one thing.

I love when a movie is part of something bigger. ‘An Inconvenient Truth’ helped invigorate the conversation on climate change. ‘Waiting For “Superman”’ challenged some big notions — sometimes not always good.

It’s so hard to tell a good story. To make a good movie really is hard, and sometimes that’s enough. But in this case, and in a few cases when it’s part of something bigger — the idea that there are 66 million girls who are out of school, each with a story like Malala’s. When you feel the loss and the potential of girls who are not getting an education, if you can feel that, then you can be inspired by what happens when a girl does get educated. You feel there’s a tremendous sense of opportunity with people seeing this movie.

Malala and I always like to say ‘What if it’s more than a movie? What if it’s also a movement? What if young girls say to their mothers and fathers, I want to go to this movie. I want to be part of this thing. I want to help the Malala Fund!’

What do you hope that audiences take away from seeing this?

DG: I hesitate because I hate to tell people what to feel. I’ve worked on this movie and held it so tight, and [then] you give it away. It’s like birthing a child now, and the child is going off to college. The movie is going to live on its own and people are going to interpret it the way they want to interpret it. I don’t like to say too much. I hope they feel something and that there’s something valuable in the telling of her story.

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/NJ-H_1-713x848.jpg)