An artist of his time, painter Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975) chronicled what it meant to be an American in the 20th century, when the nation was a democracy on the rise. Artists of all kinds were exploring the American character, not only in visual arts, but in novels, music, plays, photographyand the century’s new medium—movies.

What sets Benton apart is that his version of the American saga includes those on the margins of power.

“American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood,” a thrilling exhibition at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem through September 7th, is the first major show in 25 years devoted to the artist, whose name once was a household word. Austen Barron Bailly, curator of American Art at PEM, is lead curator of the show, which explores how Benton’s experience creating sets and promotional posters for movies shaped his art.

The works on view also tell a story of America as a land of opportunity and tragic flaws—including slavery, racial violence and environmental destruction. Benton’s eye for injustice coupled with his streamlined, modernist style wear well decades later. In this superbly staged exhibition, some of Benton’s paintings seem prophetic in 2015.

Presenting more than 100 works and complemented by a lustrous catalog of essays and color plates, after the Salem show, the exhibitwill travel to PEM’s two collaborating museums, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City and the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth. The tour willconclude at the Milwaukee Art Museum.

Benton’s values were informed by Midwestern populism. Born in 1889 in Neosho, Missouri, Thomas Hart Benton was named after a great-great uncle who was the state’s first U.S. senator. Aspiring to make an impact through art rather than politics, in 1909 he went to Paris and encountered muralist painting and European modernism, absorbing such trends as Cubism, before returning in 1912 to New York City, where he remained for two decades. After a stint in the Navy during World War I, in New York Benton taught at the Art Students League while taking jobs designing sets and painting backdrops for the movie industry His Art Student League students included his future wife, Italian-American Rita Piacenza, and fellow Midwesterners Charles Pollock and his younger brother Jackson.

By 1935 Benton was an artist of national renown, the first to have a self-portrait on the cover of Time magazine. He returned to Missouri that year, and spent the rest of his life teaching art and painting in Kansas City.

Author: Cathy Carver. © Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.Thomas Hart Benton, People of Chilmark (Figure Composition), 1920. Oil on canvas, 65 5/8 x 77 5/8 in. Hirshhorn Museum and Scuplture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington. Gift of the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Foundation.

Benton was a storyteller, observing and rendering the 99 percent of his day. Creating what he called “a peoples’ history,” he cast ordinary people as heroes in his epic narrative. At a time of rampant segregation, his protagonists included black people and Native Americans. Not without contradiction, Benton was a homophobe; he also painted a mural now housed at Indiana University that included an image of robed Ku Klux Klansmen burning a cross alongside an interracial hospital tableau.

Benton made annual journeys, sketching people while traveling by car, horseback, canoe and on foot in regions that varied from the Texas Panhandle to the Ozarks and Great Plains. In 1937, he published the first edition of his highly readable travel memoir, “An Artist in America,” which he updated twice and illustrated with his drawings.

Benton disdained modernism and the “aesthetic elite,” including abstract expressionists such as Pollock, who by 1950 usurped Benton’s place in the public eye. Although Pollock came to spurn his mentor’s naturalism, the loops of pigment in his drip paintings suggest the swirling forms of Benton’s compositions.

Benton’s signature style is spare and sensuous, melding both old school and contemporary techniques. Employing practices introduced by Italian Renaissance painters, Benton uses gradations of color and shading to create shapes and heighten depth. He sculpts bodies with elongated, serpentine curves, echoing El Greco and the Mannerists, and adopts the streamlined forms of Cubism.

All these elements are visible in the first two works on view, “Self-Portrait with Rita” (c. 1924) and “People of Chilmark (Figure Composition)” (1920), both set in Martha’s Vineyard, where the couple and their two children summered throughout their lives. In his glamorous self-portrait, Benton, who was short, casts himself as a tall, Neptune-like figure. The Chilmark composition, an ensemble of intertwined individuals, celebrates the civic ideal of many working as one in swirling chiaroscuro.

Across America

This absorbing show moves, as Benton did, among diverse American scenes. In the first of four galleries are all 14 panels of his first mural series, “American Historical Epic” (1920-28). In this self-commissioned project, Benton pulls no punches in showing the brutality of America’s founding story. The first panel, ironically titled “Discovery” (1920), shows the arrival of the first Europeans from the perspective of Native Americans, who watch as the helmeted newcomers row to shore.

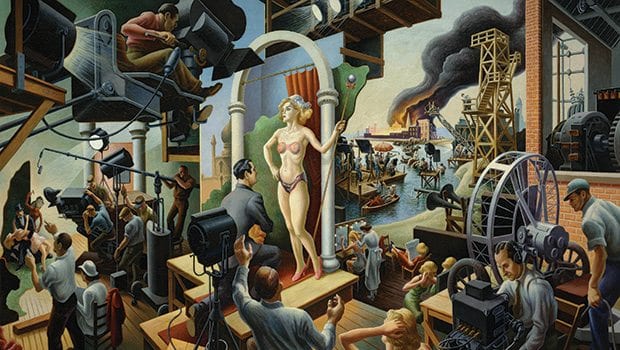

The next gallery immerses viewers in the pizzazz of Hollywood. In 1937, on assignment for Life magazine to take a behind-the-scenes look at the motion-picture industry, Benton spent a month on the set of 20th Century Fox Studios. Here, visitors can sit in director’s chairs and view big-screen projections of clips from period films, including one showing a young Humphrey Bogart. The centerpiece is Benton’s giant mural “Hollywood” (1937-38), a panorama of movie-lot life bursting with verve. A hive of workers aim lights and cameras from scaffolding while off-camera actors lounge. In the distance, a flume of smoke rises—Benton’s recurring reminder of industry’s toll on the land.

Sketches

Benton’s ink sketches show close-ups of various people at work, from a dress designer and set builders to a dance director and film editor. Also on view are Benton’s promotional posters and lithographs to publicize director John Ford’s 1939 movie of the John Steinbeck novel “The Grapes of Wrath,” a tale of a prairie family heading west after their farm is devastated by Depression-era dust storms.

Benton composed images with a filmmaker’s interest in light and depth perspective, and clay models he used to design scenes are on display.

Highlights in the next gallery, entitled Casting Characters, include Benton’s affecting painting of an African-American couple walking on a rural road and his rendering of a pensive bass player.

Hollywood joined the World War II recruiting campaign and so did Benton. The images in his 1942 “Year of Peril” posters are as alarming as their titles, including “Invasion” and “Exterminate!” In the style of action comics, they show grotesque figures performing macabre acts—borrowing from a genre of savage anti-fascist satire pioneered by Mexican artists, including Leopoldo Méndes (1902-1969). Benton’s series seems derivative, and a wrong turn for an artist whose best work simply tells the truth.

Nearby is a clip from a 1944 movie written and narrated by African-American filmmaker Carleton Moss. Intended to recruit black soldiers into a then-segregated U.S. Armed Forces, the movie gained wide civilian and military acclaim.

The section entitled Benton at Home displays Benton’s illustrations for books about such renowned Americans as Abraham Lincoln, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Edison. A fine portrait of Benton by photographer Duane Michals stands alongside theirs in this gallery of iconic Americans.

The concluding section, Benton’s Westerns, combines his later works celebrating the American frontier with earlier, edgier paintings such as “Boomtown” (1926), a restless urban scene backed by a spewing cloud of black smoke.

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Cagen-Luse_Men-at-store-e1713991226112-150x150.jpg)

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Cagen-Luse_Men-at-store-e1713991226112-848x569.jpg)