The decision of the U.S. State Department not to extend funding for the African Presidential Center (APC) at Boston University could be financially fatal for the organization and thus be at odds with the policy of major nations to increase their international presence.

Great nations traditionally expand their hegemony beyond their borders. The ancient Greeks extended Hellenistic culture, and Roman ruins from the age of Julius Caesar are still to be found in Great Britain. England, France, Spain, Belgium, Germany, Portugal and Italy all have established their presence in Africa, but the United States has very limited contact with Africa, the world’s largest remaining underdeveloped, habitable continent.

Since colonial days, Americans were daring explorers. In pursuit of a better life, Americans would risk packing their possessions in Conestoga wagons and head west. There were no roads or motels, just the open prairie and looming mountains. There was also danger from trespassing on the lands of Native Americans.

American forebears were willing to use force to expand their borders. The U.S. acquired Texas in 1821, and New Mexico, California and other territories after the Mexican War of 1846-1848. Those territorial disputes ultimately were resolved by financial settlements.

During the 19th century Britain began building the world’s largest navy to protect its growing empire. By 1920 Britain controlled all of East Africa from the Cape Colony in the south up to the Suez Canal on the Mediterranean. There was no U.S. presence.

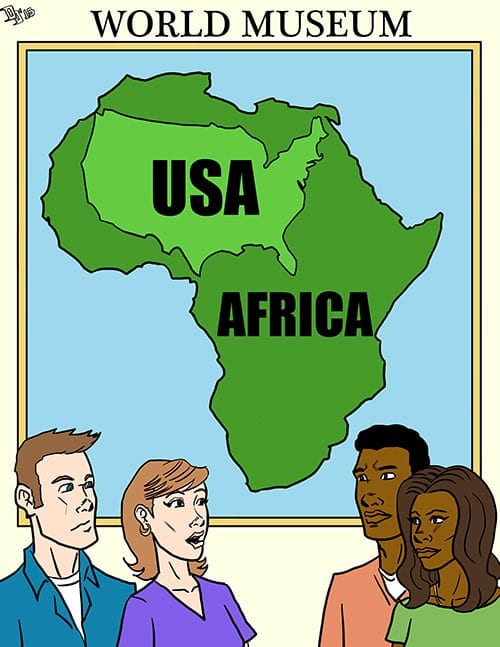

After World War II the U.S. indisputably succeeded Britain as the world’s most dominant industrial power. As African nations emerged from colonial control, the U.S. has mistakenly not enhanced its involvement in Africa to an appropriate level. One reason, perhaps, is that Americans underestimate the size of Africa. People forget that Africa is a continent, not just a country, and it is three times the size of the U.S. One country in Africa, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, is larger than the geographic size of all Western Europe.

There is a paucity of U.S. projects to develop good relations with African leaders. Programs are needed to inspire African politicians to focus on the elimination of poverty and provide sound economic development. These goals can be best achieved within democratic political processes.

Mo Ibraham, a wealthy African businessman, has established a foundation to award a prize to democratically-elected African presidents who serve the people and leave office without censure. Awardees get $5 million plus $200,000 per year for life. Ambassador Charles Stith’s APC could function as a preparatory project for those inclined to win Mo Ibraham Foundation grants.

While the U.S. certainly is not averse to using its power in pursuit of its national interests, the historical record indicates a lack of U.S. involvement in Africa since the abolition of the slave trade except for arrangements to acquire the continent’s natural resources. There was little concern about apartheid in South Africa until African Americans in Boston together with their associates protested against this inhumane policy. Gradually a national anti-apartheid policy developed.

With his Boston roots, the Secretary of State is aware of how that issue progressed. This experience should establish that it is in the best interests of the nation for the government to support the APC or similar projects. Such a program is not the primary financial responsibility of Boston University, whose limited endowment can hardly afford to fund the varied academic projects that the administration envisions.

The current news of political disruption in Africa is unsettling. This is no time to abandon projects with the potential to support the development of democratic governments.