Soledad O’Brien trains lense on police abuse, leads panel discussion at UMass Boston

Since 2007, journalist Soledad O’Brien’s Black In America series has delved into thorny issues of race in the United States. This year’s installment, Black and Blue, is no exception, examining the contours of the strained relations between blacks and law enforcement.

Last week, the award-winning journalist brought her documentary to UMass Boston, where she led panel discussions with economist and columnist Julianne Malveaux, former NAACP President Benjamin Jealous and UMass Boston Associate Professor of Africana Studies Aminah Pilgrim.

O’Brien’s previous Black In America broadcasts have covered such topics as the struggles of black women and families, educational disparities and the toll of HIV on the black community.

Her focus on police abuse comes on the heels of the high-profile police killings of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, and the resulting wave of protests across the country.

Speaking in front of an audience of several hundred UMass students and faculty, O’Brien drew parallels between the current anti-police abuse movement and past civil rights struggles, highlighting the “black lives matter” slogan, which she likened to the “I am a man” line that was popular during the Civil Rights Movement.

“What is happening that we have to state such an obvious truth?” she said.

Speaking earlier in the day with a smaller group of students in the offices of the UMass Boston newspaper, MassMedia, Pilgrim said the Black Lives Matter movement comes in response to systemic racism.

“The movement is about re-humanizing the black community, which has been de-humanized by systemic racism,” she said.

Benjamin Jealous cited work by UCLA Assistant Professor of Psychology Phillip Atiba Goff documenting unconscious biases police officers harbor toward blacks, arguing that police need training that helps them see beyond race.

“We used to think we could solve this by getting more black officers,” he told the student journalists. “While that can help, what’s clear is that you need to have officers who can deal respectfully with the community and who are secure in themselves, and who don’t harbor dangerous fears.”

O’Brien opened the panel discussion with a presentation outlining the deep disparities between blacks and whites in income, wealth and in the criminal justice system. While white families in the United States have an average of $265,000 in assets, blacks have just $28,000.

She also highlighted ways in which black actors and entertainers are under-valued by white critics, like New York Times critic Alessandra Stanley, who sought to diminish television producer Shonda Rhimes, referring to her as an “angry black woman,” and called actress Viola Davis “less classically beautiful.”

O’Brien showed clips from her Black In America broadcast, including an interview with a black New York City college student who says he has been stopped by police 100 times. The segment included an interview with former New York Mayor Rudy Guiliani, architect of the city’s aggressive stop-and-frisk policing strategy, who denies racism played a role in the strategy.

“He’s the former mayor of New York City saying there’s no systemic problem with racism, not in New York City, not in America,” O’Brien said. “I’m going to go out on a limb and disagree with him.”

Under Guiliani’s administration (1994–2001), police stops increased from 70,000 a year to 680,000 a year. While blacks and Latinos represented 83 percent of those stopped, they were less likely than whites to be found in possession of guns or drugs.

Searching for solutions

During the discussion with MassMedia students, Jealous said the targeting of blacks by law enforcement is ineffective.

“The challenge for the country is to understand that it makes all of us less safe,” he said.

The panelists suggested a number of reforms, during their conversation with the student journalists.

Jealous suggested more frequent training for officers.

“In the UK, most cops don’t even carry guns,” he noted. “And they’re trained every six months on use of force.”

Malveaux said police departments should be required to perform more extensive background checks on officers, noting that the Cleveland officer who shot 12-year-old Tamir Rice dead was found to be unfit for service in the Independence, Ohio police force by a supervisor there. Mavleaux also suggested police officers should be required to have a two- or four-year college degree.

Malveaux and the other panelists defended the actions of demonstrators in Boston and other U.S. cities who blocked traffic on interstate highways with protests against police brutality.

“People argued it’s inconvenient,” Malveaux said. “I said being 12 and being shot dead is inconvenient.”

After the panel discussion, students and faculty lined up to chat with O’Brien and the other panelists, continuing the conversations during a reception in the UMass Campus Center building.

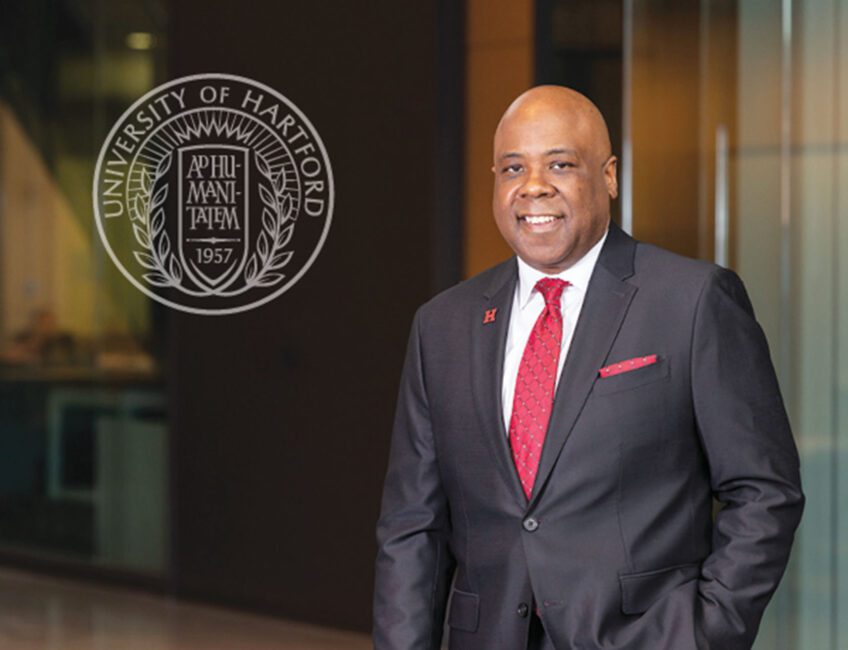

UMass Boston Chancellor J. Keith Motley said the discussion helped give UMass students a broader perspective on the anti-police abuse movement and protests in which many of them have participated.

“It’s an opportunity to put it into a historical context,” he said. “It gives a foundation for people to think in a deeper way about this.”