‘Van Gogh and Nature’ showcases artist’s evolution

Forty-five of the artist’s works on display at the Clark Art Institute

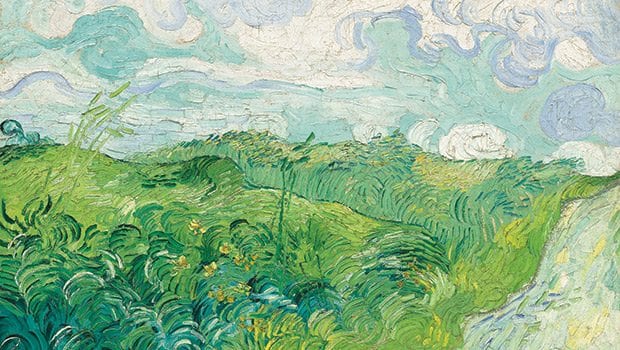

Swirling stars, blazing sunflowers, radiant iris blossoms. The paintings of Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) pulse with life and linger in the mind long after a museum visit. And they keep calling us back for more.

“Van Gogh and Nature,” an enthralling exhibition at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, MA, through September 13, explores the evolution of Van Gogh’s unique style as the distilled essence of his life-long relationship with nature.

Throughout his life, starting with his childhood in the Brabant, in the south of Holland, Van Gogh keenly observed nature. As an artist he sought to render not only what he saw, but also what he experienced, with utter immediacy. Always, in his words, “wrestling with nature,” Van Gogh endeavored not merely to replicate a scene but to render “a corner of nature seen through a temperament.”

If You Go

What: “Van Gogh and Nature”

Where: The Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 225 South St., Williamstown, MA

When: On display through Sept. 13

Tickets: Admission is $20

For more information, visit www.clarkart.edu

Presenting 45 Van Gogh paintings and drawings on loan from museums throughout the North America and Europe, the exhibition and its catalog follow Van Gogh through his too-short career as an artist — just under a decade.

The still life works and landscapes on view show Van Gogh’s evolution from the naturalism and somber palette of his beloved, often-overcast homeland to the lighter tones and semi-urban images of Paris, then move on to brilliantly-hued landscapes and close-ups of flora and fauna from his years in rural France.

Curators Richard Kendall, Sjraar van Heugten and Chris Stowijk assembled a fine catalog that complements the exhibit, mingling color reproductions of the works on view with other important pieces. Their essays quote liberally from Van Gogh’s hundreds of letters, among the most eloquent writings by any artist, ever. (An online archive of the letters can be found at http://vangoghletters.org.)

As a boy in the Netherlands, Van Gogh knew the names of every plant and insect in his yard. In his 20s, Van Gogh left the Brabant and spent a few years trying, and failing, at various occupations, finding solace in long woodland walks. Years before he decided to become an artist, he wrote to his brother Theo, “Painters understand nature and love it, and teach us to see.”

Artistic evolution

His own explorations of nature were to become central to his development as an artist. By 1881, at age 28, Van Gogh was striving to earn a living as an artist. Back home in the Brabant from 1881 to 1885, he became absorbed in portraying its landscapes and inhabitants. The first gallery at the Clark shows works from this period and, drawing from its own collections, also displays some of the works and books that influenced the artist.

On view are books of amateur natural history that Van Gogh prized, including “La Nature chez elle” (1870) by Théophile Gautier, with exquisite etchings by Karl Bodmer, and novels Van Gogh read by authors who shared his sympathy for the rural life, including George Eliot, Émile Zola and Guy de Maupassant.

Van Gogh revered the luminous naturalism of seventeenth century Dutch landscape artists such as Jacob van Ruisdael, who shared his native terrain with its cloudy skies, moors and pine woods. He also admired their heirs, including Jean-François Millet and Gustave Courbet.

Alongside Van Gogh’s works are paintings by contemporaries he admired, including the splendid “Tulip Fields at Sessenheim” (1886) by Claude Monet, aglow with ribbons of red, yellow and green pigment; and Millet’s iconic “The Sower” (c. 1865), which Van Gogh copied several times.

Author: Photo courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource, NY“Cypresses,” 1889, oil on canvas by Vincent Van Gogh.

Also on display are woodblock prints by Utagawa Hiroshige of Japan (1797-1858). Combining tactile close-ups of flowers with strong vertical elements such as bamboo reeds or raindrops, Hiroshige’s serene compositions deeply influenced Van Gogh.

Other works on view include Van Gogh’s delicate drawing “Marsh with Water Lilies” (1881), a precise rendering of grasses and flowers and their reflections in the water, bordered by a thin horizontal silhouette of the nearby town, all under a cloudy sky. Soon after making that, Van Gogh wrote to Theo that he “no longer felt so powerless in the face of nature.”

Van Gogh’s painting of birds’ nests blends a naturalist’s attentiveness with an artist’s eye for visual impact. Encircled by golden branches, the nests have tar-black innards. A landscape in muted green, gold and umber tones evokes Hiroshige with its spare geometry, which accents the forms of farmhouses, reflecting their shapes in a stream.

The next gallery shows works from Van Gogh’s formative two-year sojourn in Paris, where from 1886 to 1888 he experimented with new approaches taken by his contemporaries. His bolder palette, pigment and composition show the influences of George Seurat, Émile Bernard, Paul Gauguin and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Yet for subject matter, Van Gogh often gravitated to the city’s parks and patches of wild vegetation, and the still, semi-rural hilltop village of Montmartre where he and Theo, a respected art dealer, shared a flat. Van Gogh’s painting “Undergrowth” (1887) explodes with intense green, red and yellow whirls of brushwork.

Soon exhausted by city life, in May 1888, Van Gogh left Paris for Provence, in the south of France, where he had two extraordinarily productive years. The warm Mediterranean climate and unspoiled countryside stimulated the evolution of his style and he produced 150 paintings in two years — including many masterpieces.

Embracing primary colors and experimenting with vivid contrasts, Van Gogh left behind the gray-based palette of his homeland. On view are paintings of striking novelty and energy that introduce a new, Japan-infused flatness and hint at the abstract art era to come. A close-up of an insect, “Giant Peacock Moth” (1889), is an exuberant celebration of pattern and color. Its rich interplay of greens and yellows suggests a stained glass window, its intertwining calla lilies and leaves creating a symphony of shapes.

Nearby, “Dandelions” (1889) is a rhapsody of green and gold brush strokes. And in “A Wheatfield, with Cypresses” (1889), Van Gogh brings everything near, even the cloud formations.

Branching out

In a letter from this period, Van Gogh describes his emerging technique as a jazz pianist might speak of a keyboard improvisation. He writes, “I hit the canvas with irregular strokes which I leave as they are.”

Writing to artist Émile Bernard in defense of his fidelity to observed reality, Van Gogh speaks of not “slavishly” following nature. Instead, with color, expressive brushwork and bold, thick dabs of paint, he is striving to create “a more exalting and consoling nature.”

On the Web

An online archive of the letters is at http://vangoghletters.org

Calm, harmony, simplicity and intimacy — these are qualities Van Gogh writes that he seeks to achieve “by intensifying all the colors,” combining brilliant hues in inventive contrasts.

Yet the harmony and calm Van Gogh achieved in painting eluded him in life. During his last two years in France, he suffered debilitating illnesses and several severe breakdowns.

In May 1890, after a year in Arles, Van Gogh moved to another town in Provence, Saint-Rémy. As before, Van Gogh was enthusiastic to begin again in a new setting, enraptured by the fresh colors and terrain. He took up residence in a sanitarium housed in a medieval monastery. Living there, he found peace and calm for a time, enjoying its hospitable atmosphere and views from his windows of a large, uncultivated garden and expansive fields of wheat.

New subject matter again inspired pioneering approaches. Finding rich Rococo effects in nature, Van Gogh injects a delirious abundance of curves into “Cypresses” (1889), from the crescent moon and clouds to the green depths of the trees.

Van Gogh spent the last months of his life in Auvers-sur-Oise, a country village northwest of Paris. Here, Van Gogh was closer to Theo and friends in Paris and within reach of his family in the south of Holland. Writing to Theo shortly after his arrival, Van Gogh described finding “beautiful greenery in abundance…almost lush.”

Among the five works on display from this period is “Green Wheat Fields, Auvers” (1890). With thick impasto strokes, Van Gogh varies the light and texture of the scene and with intensity and immediacy creates a sea of movement that brings together far and near as well as earth and sky. Productive until the end, Van Gogh continued to revere nature and increasingly pioneered elemental ways to express it.

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/NJ-H_1-150x150.jpg)

![Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery](https://baystatebanner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/NJ-H_1-713x848.jpg)