Police brass squared off against a coalition of community activists last week for a debate in the City Council’s Iannella Chamber over the implementation of body-worn cameras.

During the hearing, held by the Committee on Government Operations, councilors questioned police officials and members of the Boston Police Camera Action Team on an ordinance drafted by the group and proposed by Councilor Charles Yancey.

Yancey and advocates of the cameras urged the council to implement the policy, saying they would bring a greater degree of transparency and accountability to the department. Noting that the city has paid out $41 million in lawsuits stemming from police abuse, Seguin Idowu said the cameras would be an important component in building trust.

“What we are presenting here today is not the solution, but it is a solution – part of a larger set of measures that this council should consider in eradicating the continued bias and lack of trust that we experience in this city every day,” he said.

The proposed ordinance, which Idowu and other members of the Boston Police Camera Action Team passed out at the hearing, would require officers to activate the cameras when officers respond to a call for service or at the initiation of law enforcement or investigative encounters. Officers would be required to notify subjects that they are being recorded and would be required to seek consent to record if they are entering a private residence without a warrant or are interacting with a crime victim or witness.

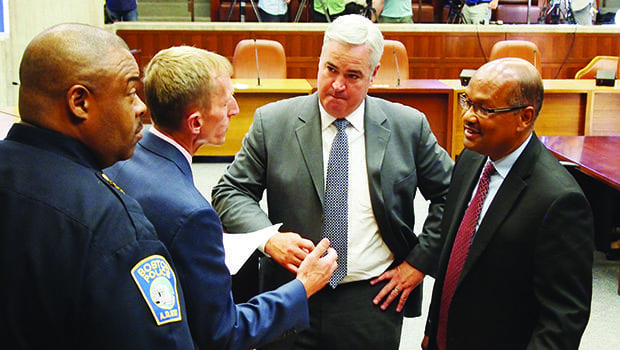

Boston Police Camera Action Team member Seguin Idowu speaks to reporters following his testimony before the City Council.

The proposed ordinance would bar police from using body cameras to record activities that are not related to a response to a call for service or an investigative encounter.

The department would be required to store the footage for six months after it has been recorded, and for three years if the footage records incidents involving use of force, events leading up to arrest for felony-level offences and encounters that have led to complaints.

The proposed ordinance, on which activists worked for several months, culled best practices from the many cities across the country that have implemented body-worn cameras, activists said.

“Among the 24 largest cities in America, only four — Jacksonville, Columbus, Nashville and Boston — have yet to implement, pilot, or announce plans to try body cameras,” said ACLU of Massachusetts Executive Director Carol Rose. “It’s time for Boston to join this nationwide effort.”

Police Commissioner William Evans said he was open to body-worn cameras, but expressed reservations, citing concerns over cost, possible privacy violations and what he said would be an erosion of the trust officers have built in the community.

“I think clearly costs are a big issue for us, but more than anything, I think the country is looking at this body camera as … the solution to everything,” he said. “Putting a device on someone’s lapel is not going to solve the historical bad relationship between the African American community and the police. What we’re doing is working on the ground level with a lot of great programs.”

Tech transparency

Evans and Police Chief William Gross cited work the department does in schools, summer camps, YMCA, youth-police dialogues and other outreach.

Evans said he would be open to a commission to study body-worn cameras, but expressed doubt that they would have a positive impact.

“Unless you get at the root of the problem, just putting technology out there is not going to solve it,” he testified.

Asked how much the technology would cost, Evans estimated with would take at least $2 million to outfit the more than 2,000 officers with the cameras and an additional $2.5 to $3 million a year to maintain the data and process requests for footage.

Councilors Yancey, Pressley and Jackson all expressed support for the ordinance.

Jackson spoke about his own experience of being stopped multiple times by police as a teenager in violation of his constitutional rights.

“I don’t want other young people to go through what I went through,” he said.

Jackson acknowledged that the Boston Police Department has worked to build relations with the community and suggested body-worn cameras could better maintain police-community relations.

“The toughest thing about trust is that it’s very difficult to build and very easy to lose,” he said. “Every city in the country is one incident away.”

“I agree,” Evans said.

“This technology is not only there to protect people who are being policed, but it’s also there to protect the police.”

Reduce risk

Jackson said the cameras would also help protect Boston taxpayers against the costly lawsuits filed against police officers, noting that the department has paid out $38 million over the last ten years.

“That would pay for approximately 13 years of the program,” he said.

Jackson and Rose also noted that the Obama administration has made millions in federal funding available for police departments to implement body-worn cameras.

Speaking to Evans’ admonishment about moving too fast to implement the cameras policy, Yancey said the council has been deliberating the matter for months.

“We’re not rushing into this. I proposed this in January. It went into committee in February of this year. It is now August. We’ve had plenty of time to study this.”

Yancey also noted that the police themselves have used video camera footage to demonstrate officers were justified in using deadly force.

“Can you name an incident, Councilor?” Evans asked.

“No, you named them for me,” Yancey replied.

“I thought you meant in our city.”

“I’m talking about Humboldt Avenue and Roslindale, where we had video evidence of an interaction between citizens and police that resulted in deadly force, and it was you, sir, who relied on the video evidence to exonerate those officers, and you made my point.”

Rose acknowledged the prevalence of commercial security cameras in Boston, but said they are not adequate to monitor police activity.

“We can’t rely on Burger King videos to do that work for us,” she said. “We have the information. We have the evidence to act. We don’t have to wait for another killing to do the right thing. We should be the leader on this. We are the hub of innovation. We are Boston strong. We should take the lead in not only adopting a policy of body-worn cameras, but implementing the privacy protections that have been drafted along with community groups … that would provide not only accountability for citizens vis a vis the police, but protections for the police.”

Other city councilors echoed Evans’ points.

Councilor Michael Flaherty, who is chairman of the Committee on Government relations, said he was concerned cameras would have a “chilling effect” on eyewitness testimony.

“Eyewitness testimony is really paramount to solving crime. What I think we really have a problem with in Boston is not community policing,” he said. “We don’t have enough people coming forward to give a name or a description or a license plate or a color of clothing. … One of my concerns is having body cameras would deter people coming forward to give testimony or to give evidence.”

Protection, privacy

Councilor Josh Zakim praised the police for doing a “phenomenal job” with community relations and questioned whether body-worn cameras would be too cumbersome for police and invasive for civilians.

“I think it’s something, and I appreciate the commissioner saying this, we need to … do in a deliberative way,” he said. “I’m someone who, whether it’s cameras on a street pole or cameras on a police officer — that makes me a little queasy.”

Other councilors raised similar concerns.

“I don’t think the body cameras are the silver bullet,” said Councilor Tim McCarthy. “They may help, but there are so many questions we haven’t answered. When do they turn on? When do they turn off? There are so many questions — storage. How long can they be stored?

Following the councilors’ testimony, Idowu said it was clear many of the councilors had not read the six-page ordinance he and others had made available to them prior to the hearing and passed out during the hearing.

“It’s frustrating,” he said. “It seemed to me as if they had not reviewed the ordinance. The ordinance addressed so many of the questions they asked.”

On the council floor, Rose expressed a similar sentiment.

“I don’t know which version of the ordinance you all are looking at, but there have been a number of discussions with privacy experts from the ACLU and around the country,” Rose said, citing the privacy protections in the ordinance. “I’m not sure it’s in front of you, but it has been proposed.”