Conversation in modern art

Peabody Essex Museum Features African American artists with new exhibit

Peabody Essex Museum Features African American artists with new exhibit “In Conversation: Modern African American Art”

Robert McNeill, New Car (South Richmond, Virginia), from the project The Negro in Virginia, 1938, gelatin silver print, Smithsonian American Art Museum.

The pleasures of art and its power to bear witness animate the exhibition of African American art on display through September 2 at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Mass.

Entitled “In Conversation: Modern African American Art,” this vibrant sampling of a century’s worth of art presents more than 100 paintings, photographs and sculpture by 43 African American artists who came of age between the early 1900s and the late 1990s.

The artists and their works span the decades that encompass the Great Migration, in which generations of black families moved from the rural South to northern industrial cities; the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s; and the struggles for civil rights that gained momentum in the 1960s.

Accompanied by a lustrous catalog, “African American Art: Harlem Renaissance, Civil Rights Era and Beyond,” this traveling exhibition debuted last year at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., and draws from its collection of African American art, the largest in the country.

Many of the artists on view bear witness to their times, while some craft abstract images with little reference to place or race.

But in most pieces, a visual language emerges informed by the influence of such figures as Alain Locke (1886-1954), the visionary leader of the Harlem Renaissance who exhorted black artists to rediscover their African heritage. Colors and patterns from Africa pervade many of the paintings and sculptures along with imagery of the rural South, as well as urban icons of factories and tenements and modernist trends in European and American art.

Peabody Essex Museum Features African American artists with new exhibit “In Conversation: Modern African American Art”

Sam Gilliam, The Petition, 1990, mixed media, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the James F. Dicke Family.

Presenting the works as both art and testimonials of their eras, the exhibition includes recorded interviews and wall text quotations from figures such as Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., Maya Angelou, James Baldwin, Muhammad Ali, Ice Cube, James Brown, Gil Scott-Heron, John Coltrane and Sidney Bechet.

Organized into three galleries, the exhibition invites visitors to discover connections among these artists and works. Coordinated by PEM curator Lynda Roscoe Hartigan, the installation juxtaposes paintings by renowned artists such as Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence with equally captivating works by lesser-known artists.

Setting the exploratory tone is Renee Stout’s evocative installation, “The Colonel’s Cabinet” (1991-1994), at the entrance to the first gallery. A stage set for an armchair traveler contemplating life in distant colonies, Stout’s work places a chair and carpet before a wonder cabinet, a collection of curiosities that was popular in the 17th century. On its shelves are jars of oddities from exotic lands and a lute-like African instrument.

Many works celebrate the resilience and beauty of black women young and old. Boston-born Sargent Johnson’s elegant copper bust, “Mask” (1930-1935) is a timeless image as is “Blackberry Woman” (1932) by Richmond Barthé of Bay Saint Louis, Mississippi. Barthé’s bronze is a slender, elongated form evoking the figures of Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti. Both artists were inspired by African statuary.

Peabody Essex Museum Features African American artists with new exhibit “In Conversation: Modern African American Art”

John Biggers, Shotgun, Third Ward #1, 1966, tempera and oil, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase made possible by Anacostia Museum, Smithsonian Institution.

Like many African Americans of his time, Benny Andrews inhabited two worlds. Raised in a family of Georgia sharecroppers, he studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago on the GI Bill. His collage “Portrait of Black Madonna” (1987) employs spare geometric shapes while incorporating homespun, everyday fabrics, venerated like relics.

Works by A-list mid-century photographers and photojournalists James VanDerZee, Gordon Parks and Roy DeCarava share gallery space with luscious gelatin silver prints by Earlie Hudnall, Jr., and photographs of church gatherings by Marilyn Nance, who at age 56 is one of the youngest artists in the show.

Bostonian Allan Rohan Crite’s irresistible “School’s Out” (1936) shows a lively South End scene of smartly dressed mothers and their rambunctious daughters. A chronicler of daily life in the South End and Roxbury at mid-century, he regarded his renderings as antidote to clichés described in his diary as “the jazz Negro or as the typical backwoods Southerner.”

Crite was a graduate of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, as was his contemporary, Lois Mailou Jones, represented here with two strong paintings, including a self-portrait.

Works in the second gallery shift from daily life to the realm of dreams and myths.

Drawing on voodoo traditions, “Zombie Jamboree” (1988) by Keith Morrison shows an Eden teeming with ghoulish beasts and allegorical figures evoking good and evil.

A surreal image of two girls at play by Hughie Lee-Smith, “Confrontation” (ca. 1970) echoes the paintings of Italian modernist Giorgio De Chirico with its dreamlike atmosphere and long shadows.

Peabody Essex Museum Features African American artists with new exhibit “In Conversation: Modern African American Art”

Earlie Hudnall, Jr., Looking Out, 1991, gelatin silver print, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase.

Painted in gorgeous hues, “Field Workers” (ca. 1948-1951) by Ellis Wilson renders a family of six in profile with the classical dignity of figures in an Egyptian frieze.

In the third gallery, works vary from social realism to pure abstraction.

The great Thornton Dial, Sr., is a former migrant farmer and steelworker whose wall-mounted and freestanding sculptures are the subject of a traveling retrospective organized by the Indianapolis Museum of Art, “Hard Truths: the Art of Thornton Dial.” A poet of cast-off materials, he injects raw fire and lyricism into his sculptures, spiritual force that keeps them from going over the edge into outsider art.

Dial’s “Top of the Line (Steel)” (1992) conjures the frenzy sparked by the beating of Rodney King, an unarmed black man, by four white policemen in Los Angeles. Anguished, ghostly faces emerge from this visual inferno, a collage of thick oil, ropes and a bent grill.

Nearby is Frederick Brown’s painting “John Henry” (1979), a bold image of protest etched in a crude, cartoon-like style and tropical palette. Resurrecting the freed slave and steel driver who, legend has it, died outperforming a steam-powered drill, Brown scrawls on the hero’s arms and hammer the names of companies that have replaced laborers with machines. By his side, a dog bares his teeth.

A steel sculpture by Melvin Edwards, “Tambo” (1993), named for South African anti-apartheid politician Oliver Tambo, combines a spear, a shovel, a wrench, and a ball and chain into a single potent image of oppression and resistance.

Although abstract, Sam Gilliam’s thrilling sculpture “The Petition” (1990), a composition of thickly layered paint on grooved metal, bursts with energy and serenity.

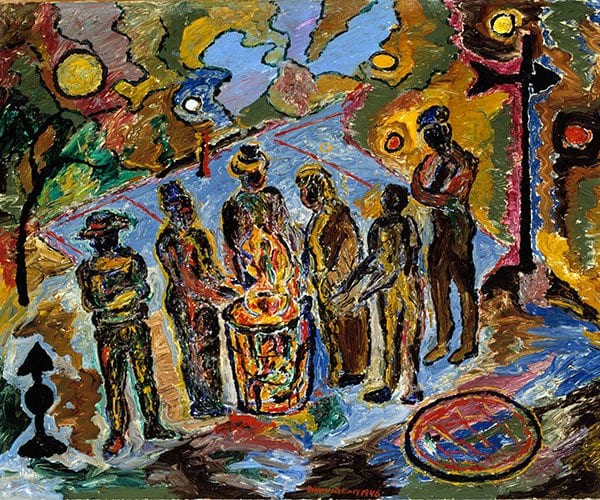

Peabody Essex Museum Features African American artists with new exhibit “In Conversation: Modern African American Art”

Charles Searles, Celebration, 1975, acrylic, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the General Services Administration, Art-in-Architecture Program.

Frederick Eversley’s “Untitled” (1974), a sleek black sphere of polyester resin with a two-way lens at its center, is both a playful optical experiment and a concise metaphor that suggests no two views are the same.

Another abstraction avowedly divorced from implied meanings is “Red Stripe with Green Background” (1986) by Felrath Hines. A vigorous activist for civil rights and the inclusion of black artists in mainstream exhibitions, Hines nevertheless believed that there is no such thing as black art. Instead, his painting is an exploration of perception.Some paintings call to mind works in other galleries. For example, Crite’s South End street scene echoes the masterpiece by John Biggers, “Shotgun, Third Ward #1” (1966). Both paintings show ladies in fine dresses and children at play. But working 30 years after Crite, Biggers is telling a more complex story. In his image, dignified people face a church with a charred roof, the order of their neighborhood torn asunder by racial violence. In powerful paintings such as this one, Biggers explores the shotgun, a traditional West African form of shelter transported to the American South, as a unit of resilience and civility.

Here and throughout the exhibition, even at times when society and institutions fail, artists are on the job, illuminating the past, the present and the future.

As Thornton Dial said, “Art is like a bright star up ahead in the darkness of the world.”