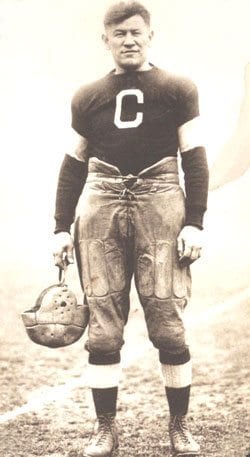

A century ago, America’s greatest athlete, Jim Thorpe, led the Carlisle Indians to an astounding 18-15 victory over Harvard, the returning national champion and the nation’s top-ranked team.

When the undefeated Carlisle team took to the field against the undefeated Crimson, the celebrated running back and kicker was a doubtful starter. Injuries in previous contests had left the 23-year-old gridiron star with, as the Boston Sunday Globe described it, “a basket-weave of strapping adhesive plaster running almost from his toe to his knee.”

Harvard itself approached the clash of the unbeatens with casual arrogance.

Mindful of Carlisle coach Pop Warner’s penchant for trick plays — and the joyous enthusiasm of his undersized Indian athletes to run them — Harvard’s imperious coach Percy Haughton had written his Carlisle counterpart a letter, warning him any chicanery would result in cancellation of the game.

According to some reports, Haughton didn’t even attend the game, boarding a train instead for New Haven to scout the Yale-Brown contest and leaving his subordinates in charge of putting in the second-string against what he considered overmatched foes.

Unfortunately for the patrician Haughton and his Harvard team, Thorpe showed up at kick-off ready to play, taking comfort in the fact that his lucky number 11 coincided with the 11/11/11 game date.

That the Native American athletes of a small Pennsylvania school had come this far was remarkable. A generation earlier, Massachusetts Sen. William Dawes had set out to break down Indian culture through the allotment act — substituting individual for communal ownership of land. Mission schools punished Indian students for speaking their language and practicing their religion.

Institutions like Harvard had long turned their back on early commitments to Indian education, diverting trust funds for Native instruction to the schooling of the colonial elite.

The mixed-race Thorpe, christened “Watha Huk,” or “Bright Path” by his mother, embodied the troubled relationship between First Americans and the European arrivistes. Descended from both the legendary Sauk Chief Black Hawk and one of the original English settlers of New Haven, he grew up chasing rabbits and deer on the Oklahoma plains and attending boarding schools far from home.

A skilled tracker, he always called hunting and fishing his favorite sports but fame came his way via football, baseball and track — diversions of the colonizers.

But under the slate-gray sky of game-day in Boston, future accolades as the 1912 Olympic decathlon champion and a pioneer of professional football were yet to come. Thorpe was focused on one thing and one thing only: Defeating Harvard.

Despite a swollen ankle and a heavily bandaged leg, Thorpe kicked first-half field goals from the 13 and 43-yard lines, taking Carlisle into the locker-room trailing Harvard 9-6.

In the second half, Carlisle played “whirlwind football,” running inventive sweeps and feints to keep the offense on the field. Thorpe kicked another field goal from the 37 to tie the game and began running more, breaking tackles on long runs to keep the Crimson at bay.

When Carlisle scored after a nine-play drive, the Indians led 15-9. Harvard, with 12 minutes left, sent in its first string. The fresh Harvard players threatened to break through the Carlisle defense, but the Indians held them off. The only way to win, Thorpe figured, was to score another field goal and wait out the final onslaught.

“As Jim saw the day going against us, he forgot his wrenched leg and sprained ankle and called for the ball,” wrote Pop Warner years later. “And how that Indian did run! After the game, one of the Harvard men told me that trying to tackle the big Indian was like trying to stop a steam engine.”

After Carlisle got bogged down at the Harvard 48-yard-line, Thorpe stepped up to kick. Quoted in Kate Buford’s “Native American Son,” Thorpe said his leg was “pretty sore” but found that the pain “sort of helped me because it made me more deliberate.”

“As long as I live, I will never forget that moment,” he recalled. “There I stood in the center of the field, the biggest crowd I had ever seen watching us …The ball came back square and true, and I swung my leg with all the power and force that I had, and knew, as it left my toe, that it was headed straight for the crossbar and was sure to go over.”

Thorpe’s teammates carried him off the field, the crowd roaring in tribute. Harvard scored a final touchdown in the waning minutes but when the game ended, only Carlisle remained unbeaten, defeating the mighty Crimson 18-15.

“This game was one of the two greatest I ever played,” Thorpe told an interviewer. The other was a victory next year over an undefeated West Point team that included young Dwight Eisenhower on the cadet squad.

As for Haughton, he said of Thorpe’s performance that day: “I realized that here was the theoretical superplayer in flesh and blood.”

In the century that has passed since Thorpe led the Indians to victory over the Crimson, Harvard has re-invigorated its 17th century roots in Native American education; Olympic medals stripped from Thorpe for playing semi-pro baseball were finally restored; and Thorpe’s mortal remains, interred in Pennsylvania after his death in 1953, may yet return to his family plot in Oklahoma.

For all that, it may be enough to remember that kick, soaring end over end under a fall sky, the hushed crowd, and the frenzied joy of the Carlisle band who carried off their champion like a conquering hero.